14,90 zł

Dowiedz się więcej.

- Wydawca: KtoCzyta.pl

- Kategoria: Fantastyka•Fantasy

- Język: polski

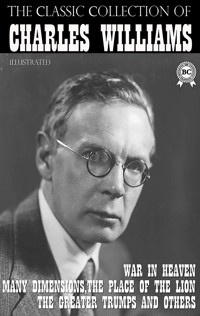

The main task of Charles Williams was to show that man must obey God. The main thing in „Many Dimensions” is the all-powerful stone that can fulfill any desire. Above of all, „Many Dimensions” is a complex image of good and evil. Williams fascinatingly shows how evil is not in a particular thing, but in what we do with these things.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi lub dowolnej aplikacji obsługującej format:

Liczba stron: 432

Podobne

Contents

I. THE STONE

II. THE PUPIL OF ORGANIC LAW

III. THE TALE OF THE END OF DESIRE

IV. VISION IN THE STONE

V. THE LOSS OF A TYPE

VI. THE PROBLEM OF TIME

VII. THE MIRACLES AT RICH

VIII. THE CONFERENCE

IX. THE ACTION OF LORD ARGLAY

X. THE APPEAL OF THE MAYOR OF RICH

XI. THE FIRST REFUSAL OF CHLOE BURNETT

XII. NATIONAL TRANSPORT

XIII. THE REFUSAL OF LORD ARGLAY

XIV. THE SECOND REFUSAL OF CHLOE BURNETT

XV. THE POSSESSIVENESS OF MR. FRANK LINDSAY

XVI. THE DISCOVERY OF SIR GILES TUMULTY

XVII. THE JUDGEMENT OF LORD ARGLAY

XVIII. THE PROCESS OF ORGANIC LAW

I. THE STONE

“DO you mean,” Sir Giles said, “that the thing never gets smaller?”

“Never,” the Prince answered. “So much of its virtue has entered into its outward form that whatever may happen to it there is no change. From the beginning it was as it is now.”

“Then by God, sir,” Reginald Montague exclaimed, “you’ve got the transport of the world in your hands.”

Neither of the two men made any answer. The Persian, sitting back in his chair, and Sir Giles, sitting forward on the edge of his, were both gazing at the thing which lay on the table. It was a circlet of old, tarnished, and twisted gold, in the centre of which was set a cubical stone measuring about half an inch every way, and having apparently engraved on it certain Hebrew letters. Sir Giles picked it up, rather cautiously, and concentrated his gaze on them. The motion awoke a doubt in Montague’s mind.

“But supposing you chipped one of the letters off?” he asked. “Aren’t they awfully important? Wouldn’t that destroy the–the effect?”

“They are the letters of the Tetragrammaton,” the Persian said drily, “if you call that important. But they are not engraved on the Stone; they are in the centre–they are, in fact, the Stone.”

“O!” Mr. Montague said vaguely, and looked at his uncle Sir Giles, who said nothing at all. This, after a few minutes, seemed to compel Montague to a fresh attempt.

“You see, sir?” he said, leaning forward almost excitedly. “If what the Prince says is true, and we’ve proved that it is, a child could use it.”

“You are not, I suppose,” the Persian asked, “proposing to limit it to children? A child could use it, but in adult hands it may be more dangerous.”

“Dangerous be damned,” Montague said more excitedly than before, “It’s a marvellous chance–it’s... it’s a miracle. The thing’s as simple as pie. Circlets like this with the smallest fraction of the Stone in each. We could ask what we liked for them–thousands of pounds each, if we like. No trains, no tubes, no aeroplanes. Just the thing on your forehead, a minute’s concentration, and whoosh!”

The Prince made a sudden violent movement, and then again a silence fell.

It was late at night. The three were sitting in Sir Giles Tumulty’s house at Ealing–Sir Giles himself, the traveller and archaeologist; Reginald Montague, his nephew and a stockbroker; and the Prince Ali Mirza Khan, First Secretary to the Persian Ambassador at the court of St. James. At the gate of the house stood the Prince’s car; Montague was playing with a fountain-pen; all the useful tricks of modern civilization were at hand. And on the table, as Sir Giles put it slowly down, lay all that was left of the Crown of Suleiman ben Daood, King in Jerusalem,

Sir Giles looked across at the Prince. “Can you move other people with it, or is it like season-tickets?”

“I do not know,” the Persian said gravely. “Since the time of Suleiman (may the Peace be upon him!) no one has sought to make profit from it.”

“Ha!” said Mr. Montague, surprised. “O come now, Prince!”

“Or if they have,” the Prince went on, “they and their names and all that they did have utterly perished from the earth.”

“Ha!” said Mr. Montague again, a little blankly. “O well, we can see. But you take my advice and get out of Rails. Look here, uncle, we want to keep this thing quiet.”

“Eh?” Sir Giles said. “Quiet? No, I don’t particularly want to keep it quiet. I want to talk to Palliser about it–after me he knows more about these things than anyone. And I want to see Van Eilendorf–and perhaps Cobham, though his nonsense about the double pillars at Baghdad was the kind of tripe that nobody but a broken-down Houndsditch sewer-rat would talk.”

The Prince stood up. “I have shown you and told you these things,” he said, “because you knew too much already, and that you may see how very precious is the Holy Thing which you have there. I ask you again to restore it to the guardians from whom you stole it. I warn you that if you do not–”

“I didn’t steal it,” Sir Giles broke in. “I bought it. Go and ask the fellow who sold it to me.”

“Whether you stole by bribery or by force is no matter,” the Prince went on. “You very well know that he who betrayed it to you broke the trust of generations. I do not know what pleasure you find in it or for what you mean to use it, unless indeed you will make it a talisman for travel. But however that may be, I warn you that it is dangerous to all men and especially dangerous to such unbelievers as you. There are dangers within the Stone, and other dangers from those who were sworn to guard the Stone. I offer you again as much money as you can desire if you will return it.”

“O well, as to money,” Reginald Montague said, “of course my uncle will have a royalty–a considerable royalty–on all sales and that’ll be a nice little bit in a few months. Yours isn’t a rich Government anyhow, is it? How many millions do you owe us?”

The Prince took no notice. He was staring fiercely and eagerly at Sir Giles, who put out his hand again and picked up the circlet.

“No,” he said, “no, I shan’t part with it. I want to experiment a bit. The bastard asylum attendant who sold it to me–”

The Prince interrupted in a shaking voice. “Take care of your words,” he said. “Outcast and accursed as that man now is, he comes of a great and royal family. He shall writhe in hell for ever, but even there you shall not be worthy to see his torment.”

„–said there was hardly anything it wouldn’t do,” Sir Giles finished. “No, I shan’t ask Cobham. Palliser and I will try it first. It was all perfectly legal, Prince, and all the Governments in the world can’t make it anything else.”

“I do not think Governments will recover it,” the Prince said. “But death is not a monopoly of Governments. If I had not sworn to my uncle–”

“O it was your uncle, was it?” Sir Giles asked. “I wondered what it was that made you coo so gently. I rather expected you to be more active about it to-night.”

“You try me very hard,” the Prince uttered. “But I know the Stone will destroy you at last.”

“Quite, quite,” Sir Giles said, standing up. “Well, thank you for coming. If I could have pleased you, of course... But I want to know all about it first.”

The Prince looked at the letters in the Stone. “I think you will know a great deal then,” he said, salaamed deeply to it, and without bowing to the men turned and left the house.

Sir Giles went after him to the front door, though they exchanged no more words, and, having watched him drive away, returned to find his nephew making hasty notes.

“I don’t see why we need a company,” he said. “Just you and I, eh?”

“Why you?” Sir Giles asked. “What makes you think you’re going to have anything to do with it?”

“Why, you told me,” Montague exclaimed. “You offered me a hand in the game if I’d be about to-night when the Prince came in case he turned nasty.”

“So I did,” his uncle answered. “Yes–well, on conditions. If there is any money in it, I shall want some of it. Not as much as you do, but some. It’s always useful, and I had to pay pretty high to get the Stone. And I don’t want a fuss made about it–not yet.”

“That’s all right,” Montague said. “I was thinking it might be just as well to have Uncle Christopher in with us.”

“Whatever for?” Sir Giles asked.

“Well... if there’s any legal trouble, you know,” Montague said vaguely. “I mean–if it came to the Courts we might be glad–of course, I don’t know if they could–but anyhow he’d probably notice it if I began to live on a million–and some of these swine will do anything if their pockets are touched–all sorts of tricks they have–but a Chief Justice is a Chief Justice–that is, if you didn’t mind–”

“I don’t mind,” Sir Giles said. “Arglay’s got a flat-footed kind of intellect; that’s why he’s Chief Justice, I expect. But for what it’s worth, and if they did try any international law business. But they can’t; there was nothing to prevent that fellow selling it to me if he chose, nor me buying. I’ll get Palliser here as soon as I can.”

“I wonder how many we ought to make,” Montague said. “Shall we say a dozen to start with? It can’t cost much to make a dozen bits of gold–need it be gold? Better, better. Better keep it in the same stuff–and it looks more for the money. The money–why, we can ask a million for each–for what’ll only cost a guinea or two...” He stopped, appalled by the stupendous vision,

Then he went on anxiously, “The Prince did say a bit any size would do, didn’t he? and that this fellow”–he pointed a finger at the Stone –“would keep the same size? It means a patent, of course; so if anybody else ever did get hold of the original they couldn’t use it. Millions... Millions...”

“Blast your filthy gasbag of a mouth!” Sir Giles said. “You’ve made me forget to ask one thing. Does it work in time as well as space? We must try, we must try.” He sat down, picked up the Crown, and sat frowning at the Divine Letters.

“I don’t see what you mean,” Reginald said, arrested in his note-making. “Time? Go back, do you mean?”

He considered, then, “I shouldn’t think anyone would want to go back,” he said.

“Forward then,” Sir Giles answered. “Wouldn’t you like to go forward to the time when you’ve got your millions?”

Reginald gaped at him. “But... I shouldn’t have them,” he began slowly, “unless... eh? O if I’m going to... then I should be able to jump to when... but... I don’t see how I could get at them unless I knew what account they were in. I shouldn’t be that me, should I... or should I?”

As his brain gave way, Sir Giles grinned. “No,” he said almost cheerfully, “you’d have the money but with your present mind. At least I suppose so. We don’t know how it affects consciousness. It might be an easy way to suicide –ten minutes after death.”

Reginald looked apprehensively at the Crown. “I suppose it wouldn’t go wrong?” he ventured.

“That we don’t know,” Sir Giles answered cheerfully. “I daresay your first millionaire will hit the wrong spot, and be trampled underfoot by wild elephants in Africa. However, no one will know for a good while.”

Reginald went back to his notes.

Meanwhile the Prince Ali drove through the London streets till he reached the Embassy, steering the car almost mechanically while he surveyed in his mind the position in which he found himself He foresaw some difficulty in persuading his chief, who concealed under a sedate rationalism an almost intense scepticism, of the disastrous chance which, it appeared to the Prince, had befallen the august Relic. Yet not to attempt to enlist on the side of the Faith such prestige and power as lay in the Embassy would be to abandon it to the ungodly uses of Western financiers. Ali himself had been trained through his childhood in the Koran and the traditions, and, though the shifting policies of Persia had flung him for a while into the army and afterwards into the diplomatic service his mind moved with most ease in the romantic regions of myth. Suleiman ben Daood, he knew, was a historic figure –the ruler of a small nation which, in the momentary decrease of its two neighbours, Egypt and Assyria, had attained an unstable pre-eminence. But Suleiman was also one of the four great world-shakers before the Prophet, a commander of the Faithful, peculiarly favoured by Allah. He had been a Jew, but the Jews in those days were the only witnesses to the Unity. “There is no God but God,” he murmured to himself, and cast a hostile glance at a crucifix which stood as a war memorial in the grounds of a church near the Embassy.” ‘Say: for those who believe not is the torment of hell: an evil journey shall it be.’” With which quotation he delivered the car to a servant and went in to find the Ambassador, whom he discovered half-asleep over the latest volume of Memoirs. He bowed and waited in silence.

“My dear Ali,” the Ambassador said, rousing himself. “Did you have a good evening?”

“No,” the young man answered coldly.

“I didn’t expect you would,” his chief said. “You orthodox young water-drinkers can hardly expect to enjoy a dinner. Was it, so to speak, a dinner?”

“I was concerned, sir,” the Prince said, “with the Crown of Suleiman, on whom be the Peace.”

“Really?” the Ambassador asked. “You really saw it? And is it authentic?”

“It is without doubt the Crown and the Stone,” Ali answered. The Ambassador stared, but Ali went on.

“And it is in the hands of the infidel. I have seen one of these dogs–”

His chief frowned a little. “I have asked you,” he said, “even when we are alone–to speak of these people without such phrases.”

“I beg your Excellency’s pardon,” the Prince said. “I have seen one of them use it–by the Permission: and return unharmed. It is undoubtedly the Crown.”

“The Crown of a Jew?” the Ambassador murmured. “My friend, I do not say I disbelieve you, but–have you told your uncle?”

“I reported first to you, sir,” the Prince answered. “If you wish my uncle –” He paused.

“O by all means, by all means,” the Ambassador said, getting up. “Ask him to come here.” He stood stroking his beard while a servant was dispatched on the errand, and until a very old man, with white hair, bent and wrinkled, came into the room.

“The Peace be upon you, Hajji Ibrahim,” he said in Persian, while the Prince kissed his uncle’s hand. “Do me the honour to be seated. I desire you to know that your nephew is convinced of the authenticity of that which Sir Giles Tumulty holds.” He eyed the old man for a moment. “But I do not clearly know,” he ended, “what you now wish me to do.”

Hajji Ibrahim looked at his nephew. “And what will this Sir Giles Tumulty do with the sacred Crown?” he asked.

“He himself,” the Prince said carefully, “will examine it and experiment with it, may the dogs of the street devour him! But there was also present a young man, his relation, who desires to make other crowns from it and sell them for money. For he sees that by the least of the graces of the divine Stone those who wear it may pass at once from place to place, and there are many who would buy such power at a great price.” The formal phrases with which he controlled his rage broke suddenly and he closed in colloquial excitement, “He will form a company and put it on the market.”

The old man nodded. “And even though this destroy him–“ he began.

“I implore you, my uncle,” the young Prince broke in, “to urge upon his Excellency the horrible sacrilege involved. It is a very dreadful thing for us that by the fault of our house this thing should come into the possession of the infidels. It is not to be borne that they should put it to these uses; it is against the interests of our country and the sanctity of our Faith.”

The Ambassador, his head on one side, was staring at his shoes. “It might perhaps be held that the Christians derive as much from Judah as we,” he said.

“It will not so be held in Tehran and in Delhi and in Cairo and in Beyrout and in Mecca,” the Prince answered. “I will raise the East against them before this thing shall be done.”

“I direct your attention,” the Ambassador said stiffly, “to the fact that it is for me only to talk of what shall or shall not be done, under the sanction of Reza Shah who governs Persia to-day.”

“Sir,” the Prince said, “in this case it is a crown greater than the diadem of Reza Shah that is at stake.”

“With submission,” the old man broke in, “will not your Excellency make representations to the English Government? This is not a matter which any Government can consider without alarm.”

“That is no doubt so,” the Ambassador allowed. “But, Hajji Ibrahim, if I go to the English Government and say that one of their nationals, by bribing a member of your house, has come into the possession of a very sacred relic they will not be in the mind to take it from him; and if I add that this gives men power to jump about like grasshoppers they will ask me for proof.” He paused. “And if you could give them proof, or if this Sir Giles would let them have it, do you think they would restore it to us?”

“Will you at least try, sir?” Ali asked.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.