Oferta wyłącznie dla osób z aktywnym abonamentem Legimi. Uzyskujesz dostęp do książki na czas opłacania subskrypcji.

14,99 zł

Najniższa cena z 30 dni przed obniżką: 14,99 zł

Najniższa cena z 30 dni przed obniżką: 14,99 zł

Zbieraj punkty w Klubie Mola Książkowego i kupuj ebooki, audiobooki oraz książki papierowe do 50% taniej.

Dowiedz się więcej.

- Wydawca: Literatura

- Kategoria: Dla dzieci

- Język: polski

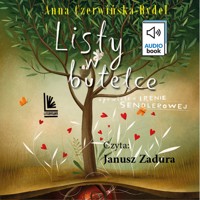

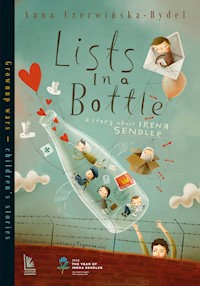

Pewnego dnia 1941 roku siostra Jolanta zrozumiała, że to, co robi dla zamkniętych w getcie przyjaciół, nie wystarczy, aby ich ocalić. „Będę pomagać inaczej”, postanawia, i narażając życie swoje i ogromnej siatki ludzi, którzy myślą jak ona, codziennie ratuje kilkoro dzieci. Ich lista, umieszczona w zwykłej butelce po mleku, którą Jolanta zakopuje pewnego dnia pod jabłonką, liczy… dwa i pół tysiąca dzieci!

„Ja tylko próbowałam żyć po ludzku… To przecież nic takiego. Każdy by tak zrobił. Trzeba podać rękę tonącemu. Nawet, jeśli nie umie się pływać, zawsze jakoś można pomóc. Nauczył mnie tego mój tatuś…”

Poznajcie historię życia Ireny Sendlerowej.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Liczba stron: 89

Popularność

Podobne

Okładka

Front page

Anna Czerwińska-Rydel

List in a Bootle

A story about Irena Sendler

Illustrations Maciej Szymanowicz

Editorial page

Anna Czerwińska-Rydel

Lists In a Bottle

A story about Irena Sendler

Original title:

Listy w butelce

Opowieść o Irenie Sendlerowej

© by Anna Czerwińska-Rydel

© by Wydawnictwo Literatura

Technical consultation: Janina Zgrzembska

Cover and illustrations: Maciej Szymanowicz

Translated by: Katarzyna Wasilkowska

Language consultation: Cátia Lamerton, Viegas Wesolowska

Editing, proofreading and setting: Aneta Kunowska, Joanna Pijewska, Aleksandra Różanek

First publication in this edition

ISBN 978-83-7672-575-8

Wydawnictwo Literatura, Łódź 2018

91-334 Łódź, ul. Srebrna 41

tel. (42) 630 23 81

www.wydawnictwoliteratura.pl

Dear Young Readers!

I am delighted that you are holding in your hands a biographical tale dedicated to a unique person. Irena Sendler – who this book is about – deserves to have her story known by more than anyone, not only by children and young people, but also by adults.

Who was Irena Sendler I had the opportunity to meet? She was modest, quiet, very wise. She spent her life helping others, often putting at risk her own health and life. She often repeated that people can only be divided into good and bad, and that a belief, nationality, colour, or ideals have no meaning. When someone expressed admiration for her heroism, she used to say that it was nothing special! She did what anyone else would do in her position. Thanks to her, many wonderful people were able to survive a terrible war, and two and a half thousand children had the chance to grow up safely.

Irena Sendler received many awards and medals, was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize twice, and for years after little was said about her...

What about you? Do you know her story? This kind old lady with the look of a good fairy, Irena Sendler, do you know what she was really like?

Read the book Lists In a Bottle. A story about Irena Sendler. I am convinced that the story here written by the author will not leave you indifferent.

It seems that letters in a bottle are something from the past. However, they are not – today people also use this form of communication, I mean mail in a bottle. I have just recently received a letter in a bottle from children. It was handed to me by Usman from Pakistan and Sidika from Guinea, who are staying in the Eleonas refugee camp in Athens. These children came to Europe, escaping the dangers of war and the loss of life tied to it. In the letter inserted in the bottle they write that they want peace and that everyone in Europe should respect each other, and respect the rights of refugees and children, who simply want to be children. They ask for help and understanding. In the camp I also met a boy who was about five years old and ran around with a small plastic handgun. I asked him why was he playing with a gun. He replied: ‘Because I do not have a teddy bear...’. Children do not want war, weapons or violence. They all want a normal, happy, safe childhood. And that is what Irena Sendler fought for so much and today we are fighting for the same. Therefore, for the motto of 2018 [1] I chose the words of this wonderful person, and the heroine of this book: ‘Give your hand to anyone who is drowning!’.

I greet you warmly and wish you a pleasant reading.

Marek Michalak

MThe Ombudsman for Children

MThe Chancellor of the International Chapter of the Order of the Smile

The book is a letter from the author to a friend, that is the reader.

Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz

PART I The Post Office

Every letter has its face.

Kornel Makuszyński

FOUR-THIRTY P.M.

Warsaw, July 18, 1942

She looked at her watch.

‘A quarter past four,’ she murmured. ‘A little longer and I’ll be late. We’ve been waiting for over an hour. What’s going on there?’ she asked loudly.

‘Probably someone tried to enter without a pass,’ answered a man standing in front of her.

‘People still believe in miracles,’ she shook her head.

‘Miracles happen, nurse Jolanta [2],’ the man smiled.

‘Do you know me?’

‘You come to the ghetto several times a day, bring clothes, typhoid vaccines, medicines, food and the most necessary things, right? After a while, faces become easy to recognise. Names too...’ he looked at her decidedly.

‘I thought that when I’m not wearing my nurse uniform...’ she stopped as the crowd in front of her began to retreat under the pressure of the closing barrier. ‘Twenty past four,’ she looked at her watch again. ‘I will not make it...’.

‘Where are you going in such a hurry?’ asked the man.

She handed him a piece of paper she held squeezed in her hand.

It transcends the text – being a mirror of the soul, he read quietly. It transcends emotion – being an experience. It transcends mere acting – being the work of children. [3]’ he hung his voice. ‘An invitation to a performance at the Korczak’s Orphans’ Home... At four-thirty... Please, follow me,’ he pulled her hand.

They broke through the crowd, ran across the street and entered one of the houses, then rushed down the stairs to the basement. It was dark, damp and cramped, but the man who led her seemed to know his way round as he walked decisively, turning once to the left then to the right without any hesitation, as if the gloomy corridors were his daily walking route. Finally, they reached a small door. The man opened it and they went outside.

‘Do you see? Here we are,’ he smiled and looked at her triumphantly. ‘Sometimes I use this shortcut when I bring things for Korczak’s kids. This way I avoid unnecessary waste of time at the gate. And nerves...’ he glanced at his watch. ‘Two minutes to four-thirty. You’d better run,’ he waved his hand.

‘Thank you. And what is your name?’ but she spoke into emptiness as the stranger had disappeared. In a hurry, she ran up a few steps and finally, panting, she entered the room where the lights had just gone out. The performance began.

THEATRE

‘You cannot leave the room,’ said a boy seriously, dressed in a doctor’s uniform. ‘You’re very sick. Going outside may result in death.’

‘Doctor, I do not want to die...’ sighed a slim boy lying in bed. ‘But I also do not want to spend my whole life alone. I love the world! I love people! I want to meet them, talk to them. I want to have friends!’ the small actor acclaimed with great emotion.

‘You must lie in bed, Amal,’ the doctor shook his head. ‘I know it is difficult, but that’s how it is, bitter remedies and good advice the better they help, the harder they are to swallow.’

Amal was silent for a moment, then he smiled weakly.

‘I have a window from which I can look through,’ he said. ‘On its other side I will meet different people. Maybe somebody will drop by and talk to me? Anyway, there is also the post office. I can write letters and send them to anyone, even to the king himself, and wait for an answer. How good that there is the post office! Thanks to letters, everyone in the world can be close to each other, even if they are really far away. Post doesn’t care, what someone is like – what one looks like, what one does, whether he or she are healthy or sick, tall or short, old or young, fat or thin, full or hungry, what is one’s religion or beliefs or what colour is their skin. Anyone can write a letter and wait for an answer... I will wait for a response from the king himself. He will let me go outside...’ said the boy and dropped his head into the pillow.

The curtain (which was in fact a wide bed sheet) covered the stage. There was silence. Even though the performance had come to an end, the stage was unveiled once again and the small actors lined up in a row waiting for another applause. However, no one moved.

‘Bravo, my dears, bravo!!! You were wonderful!’ Doctor Korczak [4] broke the silence and approached the children. He embraced them heartily and the audience finally began to clap. Some wiped tears away, some approached and congratulated the young artists and miss Estera [5] who directed the whole show, and others stood thoughtfully still experiencing Rabindranath Tagore’s [6] play.

‘Doctor,’ she approached Korczak and shook his hand. ‘I still cannot get over how you do it! In these conditions, times and circumstances, you organise a real theatre...’

‘Nurse Jolanta,’ the teacher looked at her through his slightly misty glasses. He took them off and rubbed them with solemnity, then he put them back on and looked at her again. ‘Actually, Irena,’ he said. ‘Don’t you do the same thing?’ he patted her hand.

Footnotes

[1] On the initiative of the Ombudsman for Children, Marek Michalak, the Parliament of the Republic of Poland proclaimed 2018 the Year of Irena Sendler.

[2] Nurse Jolanta – Irena Sendler’s war nickname. She went under the name of “nurse Jolanta" while she worked underground. As a nurse, she was able to enter the ghetto and help Jews.

[3] A quote from the invitation to The Post Office performance at Janusz Korczak’s Orphans’ Home. The text on the invitation was written by Władysław Szlengel.

[4] Doctor Janusz Korczak (1878-1942) – doctor, teacher, writer, social activist.

[5] Estera Winogronówna – a tutor at Janusz Korczak’s Orphans’ Home. She was in charge of a dance group and organised theatre performances. Estera Winogronówna was detained at the beginning of the ghetto liquidation, immediately after July 22, 1942. Janusz Korczak tried to save her, he intervened in this case with the authorities after her detention. In vain.

[6] Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) – Indian poet, philosopher, composer, painter, teacher, Nobel laureate in Literature for 1913.