14,90 zł

Dowiedz się więcej.

- Wydawca: KtoCzyta.pl

- Kategoria: Thriller, sensacja, horror

- Język: polski

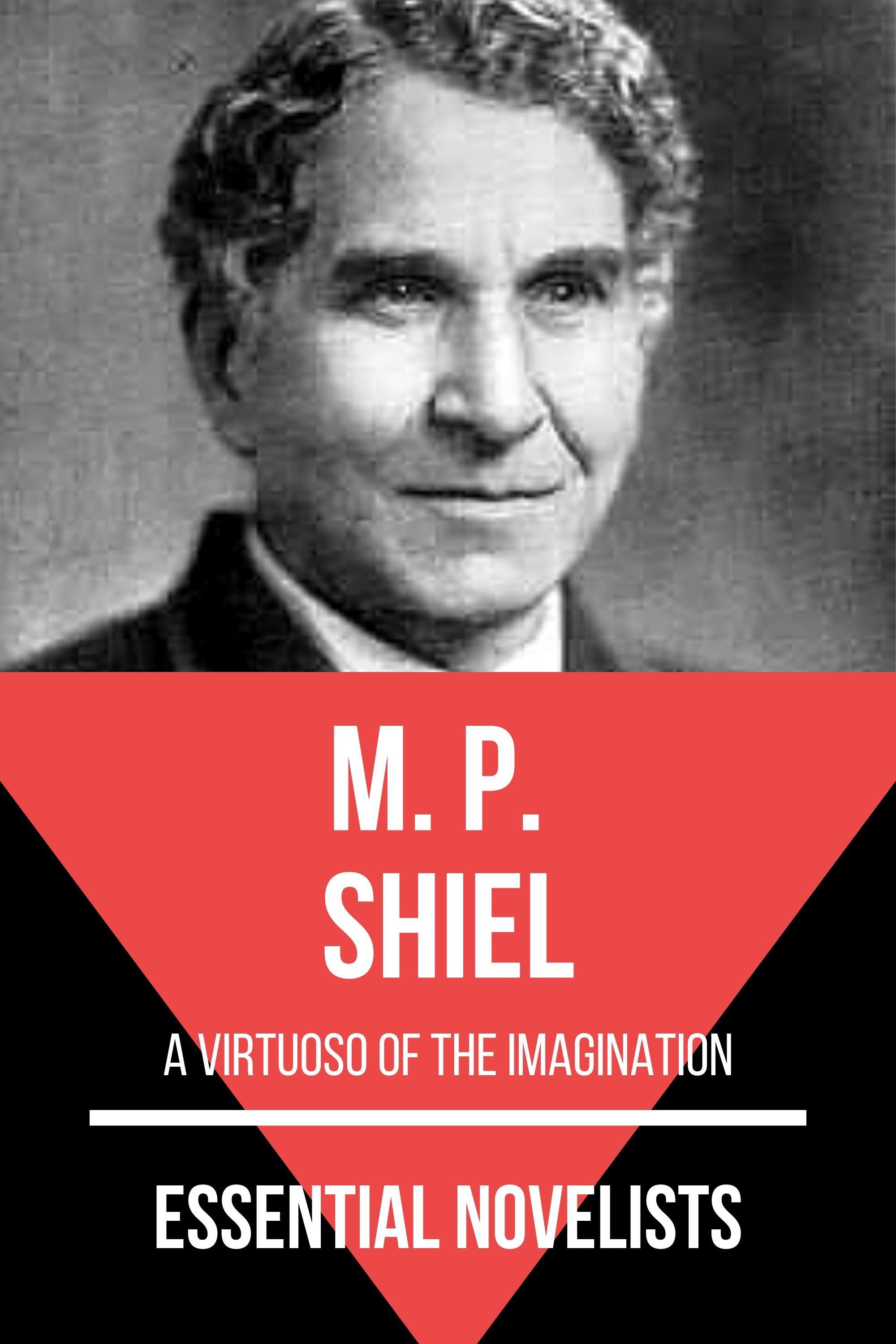

Not all invasion threats were purported to come from the Germans, the French or from Anarchists: in M.P. Shiel’s Yellow Danger it is an army of Chinese who invade Europe. In „The Yellow Danger” Mr. Shiel described in lurid colors the possibilities of the overwhelming of the white world by the yellow man, a possibility for the imagining of, which he claimed no originality. „The Yellow Danger” has been the bugbear of the Russians ever since the days of Tamerlane. But it must be admitted that in his new story. This made Shiel’s popular reputation and was almost certainly the most commercially successful of the twenty books published during his first creative period, 1889-1913.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi lub dowolnej aplikacji obsługującej format:

Liczba stron: 595

Podobne

Contents

CHAPTER I. THE NATIONS AND A MAN

CHAPTER II. THE HEATHEN CHINEE

CHAPTER III. RUMOURS OF WAR

CHAPTER IV. FIRST BLOOD

CHAPTER V. HOW ENGLAND TOOK THE NEWS

CHAPTER VI. HARDY

CHAPTER VII. IN THE CHANNEL

CHAPTER VIII. THE BATTLE

CHAPTER IX. JOHN HARDY GIVES AN ORDER

CHAPTER X. JOHN HARDY AMONG WOMEN

CHAPTER XI. JOHN HARDY AMONG THE NATIONS

CHAPTER XII. THE AWAKENING

CHAPTER XIII. JOHN AND YEN

CHAPTER XIV. THE VANISHED FLEET

CHAPTER XV. THE SUICIDE OF EUROPE

CHAPTER XVI. THE LOVE WHICH FOO-CHEE BORE TO AH-LIN

CHAPTER XVII. THE CHINESE IRON

CHAPTER XVIII. SIN-WAN

CHAPTER XIX. ‘THE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY’

CHAPTER XX. ‘WHAT A FACE!’

CHAPTER XXI. MURRAY’S DIARY

CHAPTER XXII. MURRAY’S DIARY (CONTINUED)

CHAPTER XXIII. THE FROWN OF ENGLAND

CHAPTER XXIV. BEFORE THE BATTLE

CHAPTER XXV. THE GREATER WATERLOO

CHAPTER XXVI. THE YELLOW DANGER

CHAPTER XXVII. THE THREE GOSPELS

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE YELLOW TERROR

CHAPTER XXIX. THE WEAK POINT

CHAPTER XXX. THE CHINESE SCREAM

CHAPTER XXXI. THE MEETING

CHAPTER XXXII. ‘TO-DAY’

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE ‘CRIME’ OF HARDY

CHAPTER XXXIV. THE BLACK SPOT

CHAPTER I. THE NATIONS AND A MAN

As all the world knows, the Children’s Ball of the Lady Mayoress takes place yearly on the night of ‘Twelfth Day,’ 6th January. In the year ‘98 the function was even more successful than usual, owing to Sir Henry Burdett’s fine idea that the children should be photographed in support of the Prince of Wales’ Hospital Fund. The little Walter Raleighs, Amy Robsarts, flocked in throngs to the photographer’s studio adjoining the grand salon of the Mansion House; while all that space outside between the Mansion House, the Bank, and the Stock Exchange was a mere mass of waiting, arriving, and departing vehicles.

If anything tended to take a little of their exuberance from this and other New Year jubilations, it was a certain cloudiness in the political sky; nothing very terrifying; yet something so real, that nearly every one felt it with disquiet. An Irish member, celebrated for his ‘bulls,’ was heard to say: ‘Take my word for it, there’s going to be a sunset in the East.’ Men strolled into their clubs, and, with or without a yawn, said: ‘Is there going to be a row, then?’ Some one might answer: ‘Not a bit of it; it’ll pass off presently, you’ll see.’ But another would be sure to add: ‘Things are looking black enough, all the same.’

It was just as when, on a clear day at sea, low and jagged edges of disconnected clouds appear inkily on the horizon-edge, and no one is quite certain whether or not they will meet, and whelm the sky, and sink the ship.

But the horizon had hardly darkened, when, again, it cleared.

The principal cause of fear had been what had looked uncommonly like a conspiracy of the three great Continental Powers to oust England from predominance in the East. First there was the seizure of Kiao-Chau, the bombastic farewells of the German Royal brothers; then immediately, the aggressive attitude of Russia at Port Arthur; then immediately, the rumour that France had seized Hainan, was sending an expedition to Yun-nan, and had ships in Hoi-How harbour.

All this had the look of concert; for within the last few years it had got to be more and more recognised by the British public that centuries of neighbourhood had fostered among the Continental nations a certain spirit of kinship, in which the Island-Kingdom was no sharer.

In the course of years the Straits of Dover had widened into an ocean. Europe had receded from Britain, and Britain, in her pride, had drawn back from Europe. From the curl of the moustache, to the colour and cut of the evening-dress, to the manner in which women held up their skirts, there was similarity between French and German, between German and Russian and Austrian, and dissimilarity between all these and English.

It is true that the Russian hated the German, and the German the Russian and the French; but their hatred was the hatred of brothers, always ready to combine against the outsider. This had been begun to be suspected, then recognised, by the British nation. Alone and friendless must England tread the wine-press of modern history, solitary in her majesty; and if ever an attempt were made to stop her stately progress, she was prepared to find that her foe was the rest of Europe.

But very soon after the unrest had arisen, it began to subside. France denied the annexation of Hainan; the semiofficial Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, inspired by Wilhelm, painted Germany as the patron of commerce, with an amiable weakness for theatrical displays; Russia was defeated in the matter of the removal of Mr. MacLeavy Brown, and seemed sufficiently limp after it; while spirits were raised by the probable guarantee of a Chinese loan by the British Government.

But meanwhile, at the children’s ball at the Mansion House, events were working in a quite different direction from that of peaceful settlement.

Ada Seward was the presiding deity in the nursery of Mrs. Pattison of Fulham. On the night of the 6th, Dr. and Mrs. Pattison had to be present at a ball in the West End, and Ada on that night was busy; for it was necessary for her, first of all, to convey Master Johnnie Pattison, costumed as Francis I., to the Mansion House; and then to hurry homeward again to take Miss Nellie Pattison to a children’s evening with charades in South Kensington.

The fact that it was wet when she reached the Mansion House may have had something to do with her troubles. The landing-place was occupied by some other carriages, and dismounting with her charge, an umbrella over him, she cried to the coachman in a hurried manner through the drizzle:

‘Wait till I come back.’

The man afterwards declared that he understood her to say:

‘Go away, and come back.’

At any rate, when Ada again came forth into the crush to look for the Pattison brougham, it was nowhere to be found.

And now her lips went up in a pout of vexation. ‘What on earth is any one to do now?’ she said. She was pressed for time, and yet at a loss.

The throng of private carriages seemed to have banished all cabs from the region of the Mansion House. She looked and saw none; then into her pocket, and found only sixpence. These two circumstances decided her against the cab. Instead, she ran a few yards, dodging among the carriages, and at the entrance to Poultry, skipped into a moving ‘bus.

She sat in a corner for five minutes, with agonised glances out of the door at the slowly receding clocks. Then some one–a man sitting nearly opposite, whom she had not noticed–addressed her:

‘Why, Miss Ada, is that you?’

‘Oh!’ she cried, ‘Mr. Brabant, is that you? It’s a long time since–how are you?’

‘Well, I’m pretty fair, Miss Ada, as times go, you know. Hope you are the same.’

‘Still in the army?’

‘Oh yes–the Duke of Cambridge’s Own, you know. You living in London now?’

‘Yes–at Fulham.’

Here conversation flagged; and in that minute’s interval, Brabant, with a sudden half-turn to his left, said:

‘Just allow me to introduce you to my friend here–Miss Seward–Dr. Yen How.’

In the light of the ‘bus lamp Ada Seward saw a very small man, dressed in European clothes, yet a man whom she at once took to be Chinese. With a wrinkled grin, he put out his hand and shook hers.

He was a man of remarkable visage. When his hat was off, one saw that he was nearly bald, and that his expanse of brow was majestic. There was something brooding, meditative, in the meaning of his long eyes; and there was a brown, and dark, and specially dirty shade in the yellow tan of his skin.

He was not really a Chinaman–or rather, he was that, and more. He was the son of a Japanese father by a Chinese woman. He combined these antagonistic races in one man. In Dr. Yen How was the East.

He was of noble feudal descent, and at Tokio, but for his Chinese blood, would have been styled Count. Not that the admixture of blood was very visible in his appearance; in China he passed for a Chinese, and in Japan for a Jap.

If ever man was cosmopolitan, that man was Dr. Yen How. No European could be more familiar with the minutiae of Western civilisation. His degree of doctor he had obtained at the University of Heidelberg; for years he had practised as a specialist in the diseases of women and children at San Francisco.

He possessed an income of a thousand tael (about £300) from a tea-farm; but his life had been passed in the practice of the grinding industry of a slave. Nothing equalled his assiduity, his minuteness, his attention to detail. He had once written to the Royal Observatory at the Cape pointing out a trifling error in a long logarithmic calculation of the declension of one of the moons of Jupiter, originating from the observatory.

In the East he could have climbed at once to the very top of the tree–even in the West, had he chosen. But he chose to lie low, remaining unnoticed, studying, observing, making of himself an epitome of the West, as he was an embodiment of the East.

In whatever country he happened to be–and he was never for many years in any one–he was most often to be found in the company of people of the lower classes; and of these he had a very intimate knowledge. So great was his mental breadth, that he was unable to sympathise with either Eastern or Western distinctions of class and rank. He often struck up chance friendships with soldiers and sailors about the capitals of Europe; and these patronised and exhibited him here and there.

Yen How knew that he was being patronised, and submitted to it–and smiled meekly. In reality, he cherished a secret and bitter aversion to the white race.

He had two defects–his shortness of sight, which caused him to wear spectacles; and his inability, in speaking without effort, to pronounce the word ‘little.’ He still called it ‘lillee.’

On that date of 6th January, when he drove westward with Brabant and Ada Seward, he was perhaps forty years of age, but seemed anything between sixteen and sixty; a hard, omniscient, cosmopolitan little man, tough as oak, dry as chips.

Yet in that head were leavening some big thoughts; and his heart was capable of tremendous passions.

In reality, could one have known it, as he fared onward through the drizzle in the trundling ‘bus, smiling behind his spectacles, he was the most important personage in London, or perhaps in the world.

Dr. Yen How was capable of anything. In him was the Stoic, and the cynic, and the tiger; with a turn of the mind he could become a savant or a statesman, or a crossing-sweeper, or a general. He possessed this excellence: a clear brain.

By one of those extraordinary freaks of nature for which there is no accounting, this man wanted to see Ada Seward a second time after parting with her that night.

Brabant, who had known her in her native town of Cheltenham, accompanied her to the gate of the Pattison villa, Yen How with them.

As he was leaving her, the little doctor put his mouth to her ear, and whispered hurriedly:

‘I will wait here to-morrow night at eight for one lillee kiss.’

The girl was astounded.

‘Well, the idea!’ she just gasped.

Before she could proclaim her indignation, the two men turned off.

Till he reached his home in Portland Street, Yen How was engaged in one long, continuous, secret smile–a smile at his own expense. This outburst of his in the role of lover was new to him, absolutely. His relations with women hitherto had consisted in the business of curing their sicknesses. By what subtle physiological or psychological affinity this one particular English girl had been able to evoke from this particular dry Chino-Japanese a request for ‘one lillee kiss,’ he was unable to divine. Such an affinity there undoubtedly was; but its origin lay among reasons far too abstruse for the unravelling of Yen.

Yen How smiled that first night, but he presently found that this was no smiling matter.

At eight the next evening he was duly at the Pattison gate; but, alas, no Ada was to be seen. Ada, however, was there, though invisible. She, with the Pattison cook, whom she had brought out to enjoy the fun, was hiding behind a shrubbery, and peering through, shaking with laughter at the futile waiting of the little doctor.

And now Yen How, for the first time in his life, began to suffer on account of a woman.

He loved; and in his love was the concentrated passion of many other men. Melted rock is lava–and he suffered.

He used at night to hang about the house, which was lonely at that hour, waiting. To his patience there was no end–to his resolution to possess her, by fair means or foul, no end.

Even in the matter of love the Eastern is essentially different from the Western. It is impossible for us, in anything, to understand them, so foreign are they. With us love is frequent, a powerful mood; with them the whole man is involved, and love becomes a passion having all the characteristics of ordinary flame.

One night, as he lurked about, he met her returning from some shopping. By this time Yen How had become a standing joke for Ada in the kitchen and the servants’ bedroom. He walked to her.

‘Ah,’ he said with sideward head, and a cajoling smile, ‘you are here, then? You will give poor Yen How one lillee kiss?’

The whole idea of courtship possessed by this clownish and unpractised lover consisted in asking for one little kiss. Ada Seward’s views of the matter were more elaborate. She despised his strong simplicity.

‘Perhaps you are not aware whom it is you are talking to,’ she said.

Yen was aware; he could have shut his eyes and drawn an exact picture of her face.

‘Ah,’ he said, ‘not even one lillee–’

‘I’ll give you one lillee box of soap to wash your face, if you like!’ she cried, running and looking back. The house was near; he could not overtake her.

Perhaps it would have been impossible for Miss Seward to utter words more calculated to drive Yen to madness than this reference to ‘soap.’ If his suit was hopeless, it was now borne in upon him that it was hopeless on account of his race. The girl did not listen to him, and reject him; she rejected him without taking him into consideration at all. It was as though a mule, or a cat, had asked her to be his.

But his persistence did not fail. He flung his other pursuits to the winds, and the Pattison villa became for him the centre of the world. Sometimes he caught bright glimpses of her. Once again he met her in the street, and once again she overwhelmed him with jeers. So passed January, February, and March.

To Yen How, the bourgeois, the thought never at all occurred that the girl was below bourgeois class. He was a great man, and merely saw in Ada the eternal woman. Dukes marry duchesses; but the Goethes, the Mahomets, wed cooks and water-carriers. On that very plan was built Yen How.

At the beginning of April he stood one night outside the Pattison gate, when he saw her. It was eleven o’clock; she was coming from the theatre, leaning on the arm of Private Brabant. Brabant, since their meeting in the ‘bus, had several times been ‘out’ with her.

As the two approached, Ada saw the little doctor.

‘There’s that little Chinaman again, John,’ she said, pressing Brabant’s arm. ‘It’s getting too much of a good thing now, isn’t it?’

‘Confound the little rat,’ said Brabant; ‘he wants his nut cracked, I should think, doesn’t he?’

The doctor tripped up to them, smiling nervously. Before he could speak, Brabant, who had had a glass, said:

‘Come, come, Mr. Yen How, get out of this. Can’t you see the young lady doesn’t want you fooling round her?’

‘Well–but–my soldier friend,’ said Yen, ‘there is no harm done–’

‘Come, get out of it!’ said Brabant more roughly.

‘No, no, you go too fast, you see,’ began Yen apologetically.

‘Are you going–yes or no?’ said Brabrant, now flushing angrily.

‘Go away, why don’t you?’ put in Ada.

‘Ah! I–I am here to see my lillee girl,’ hazarded Yen.

‘Oh, don’t be a stupid little goose of a Chinaman! Just fancy!’ she said.

This was the most unkindest cut of all for Yen. He winced, touched with anger.

‘Are you going or not?’ said Brabant, an ultimatum in his tone.

‘No!’ said Yen; then, more decidedly, ‘No, no!’

Brabant put out his arm and pushed him on the shoulder.

It was not a violent push, but in an instant the doctor’s face was almost black with rage. He had in his hand a stout bamboo stick, which he at once lifted and slashed with terrible force across the soldier’s cheek, leaving a bruised weal which Brabant bore with him to the grave.

In retaliation the soldier lifted his large and bony fist, and sent it into the doctor’s face. Yen How dropped.

The street was deserted. Not knowing what to do, the girl and the soldier bent over him for five minutes, when, to their surprise, Yen How raised himself slowly, placed his handkerchief against his red and dripping face, and slowly limped away without a single word.

Once he stopped deliberately as he moved off, turned, and looked at them; and in the moonlight they distinctly saw him ‘twice shake his forefinger warningly in their direction.

Then he went on his way.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.

This is a free sample. Please purchase full version of the book to continue.