Oferta wyłącznie dla osób z aktywnym abonamentem Legimi. Uzyskujesz dostęp do książki na czas opłacania subskrypcji.

14,99 zł

Najniższa cena z 30 dni przed obniżką: 14,99 zł

Najniższa cena z 30 dni przed obniżką: 14,99 zł

Zbieraj punkty w Klubie Mola Książkowego i kupuj ebooki, audiobooki oraz książki papierowe do 50% taniej.

Dowiedz się więcej.

- Wydawca: Prószyński i S-ka

- Kategoria: Fantastyka•Fantasy

- Język: polski

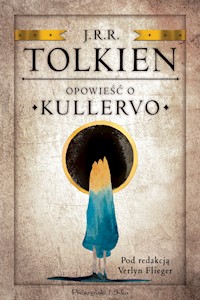

Opowieść o Kullervo” to niepublikowana dotąd opowieść fantastyczna J.R.R. Tolkiena. Jej bohater jest chyba najmroczniejszą i najbardziej tragiczną spośród wszystkich stworzonych przez niego postaci. „Nieszczęsny Kullervo”, jak nazywał go Tolkien, wychowuje się w gospodarstwie swego wuja Untamo, który zabił mu ojca, porwał matkę, a w dzieciństwie trzy razy usiłował pozbawić go życia. Trudno się dziwić, że młody chłopak wyrasta na pełnego gniewu i goryczy samotnika – kocha go tylko siostra Wanōna, a strzegą magiczne moce czarnego psa Mustiego. Untamo, choć sam też włada czarami, boi się bratanka i sprzedaje jako służącego kowalowi Asemo. Kullervo zaznaje tam nowych upokorzeń ze strony żony kowala i w odwecie doprowadza do jej śmierci. Postanawia powrócić do domu i wywrzeć zemstę na zabójcy swego ojca, jednak okrutne przeznaczenie kieruje go na inną, mroczną ścieżkę i prowadzi do tragicznego finału.

Tolkien stwierdził, że „Opowieść o Kullervo” była zalążkiem jego pierwszych prób tworzenia własnych legend. Niewątpliwie Kullervo był pierwowzorem Túrina Turambara, tragicznego bohatera „Opowieści o dzieciach Húrina”, jednej z najbardziej przejmujących historii składających się na legendarium „Silmarillionu”. Odczytana z rękopisu Tolkiena i opublikowana tu wraz z notatkami autora oraz jego szkicami na temat fińskiego eposu „Kalevala”, który stanowił główne źródło inspiracji pisarza – „Opowieść o Kullervo” okazuje się jednym z najważniejszych, choć głęboko ukrytych fundamentów wykreowanego później przez Tolkiena świata. Jej związki z głównymi dziełami autora „Władcy Pierścieni” przedstawia w szkicu, dołączonym do zredagowanych przez siebie materiałów, Verlyn Flieger, znana badaczka twórczości Tolkiena.

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973) jest twórcą Śródziemia oraz autorem wspaniałych klasycznych powieści „Hobbit”, „Władca Pierścieni” i „Silmarillion”. Jego książki zostały przetłumaczone na ponad pięćdziesiąt języków i sprzedały się w milionach egzemplarzy na całym świecie.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Liczba stron: 288

Popularność

Podobne

Tytuł oryginału

THE STORY OF KULLERVO

Originally published in the English language

by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

under the title The Story of Kullervo

All texts and materials by J.R.R. Tolkien

© The Tolkien Trust 2010, 2015

Introductions, Notes and commentary

© Verlyn Flieger 2010, 2015

[Tolkien monogram]® and ‘Tolkien’®

are registered trademarks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

Projekt okładki Wojciech Wawoczny

Ilustracja na okładce

Jacket layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

The Land of Pohja by J.R.R. Tolkien © The Tolkien Trust 1995,

Reproduced courtesy of The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford,

from their holdings labelled MS Tolkien Drawings 87, folios 18, 19

The illustrations and typescript and manuscript pages are reproduced courtesy of The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford and are selected from their holdings labelled MS. Tolkien Drawings 87, folios 18, 19, MS Tolkien B 64/6, folios 1,2,6 & 21 and MS Tolkien B 61, folio 126.9.

Redaktor prowadzący Monika Kalinowska

Redakcja Marek Gumkowski

Korekta Mariola Będkowska

ISBN 978-83-8295-517-0

Warszawa 2016

www.proszynski.pl

Wstęp

Kullervo, syn Kalervo1, to być może najmniej sympatyczny bohater Tolkiena: jest nieokrzesany, ponury, wybuchowy, a do tego nieatrakcyjny fizycznie. Jednakże te cechy przydają realizmu jego postaci i sprawiają, że wbrew nim, a może ze względu na nie, Kullervo jest w przewrotny sposób pociągający. Cieszę się, że mam okazję przedstawić ową złożoną osobowość szerszemu gronu czytelników. Jestem także wdzięczna, że mogę ulepszyć moje pierwsze odczytanie tego rękopisu, uzupełnić nieumyślne opuszczenia, poprawić wątpliwe odczytania i usunąć błędy, które na etapie druku wkradły się do tekstu. Mam nadzieję, że obecnie oddaje on poprawnie intencje autora.

Od czasu pierwszej publikacji tej opowieści powstał cały szereg prac na temat jej roli w rozwoju qenii, wcześnie stworzonego przez Tolkiena prajęzyka. John Garth w artykule „The road from adaptation to invention” [‘Od adaptacji do tworzenia’] („Tolkien Studies” [‘Badania nad Tolkienem’] t. XI, s. 1–11) i Andrew Higgins w drugim rozdziale swojej nowatorskiej rozprawy doktorskiej na temat wczesnych języków Tolkiena „The Genesis of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Mythology” [‘Geneza mitologii J.R.R. Tolkiena’] (Cardiff Metropolitan University, 2015) zbadali imiona osób i nazwy miejsc w zachowanych szkicach Tolkiena oraz ich odniesienia do wymyślonego przez niego języka. Prace tych dwóch autorów pomnażają naszą wiedzę o wczesnych dziełach Tolkiena i przyczyniają się do lepszego zrozumienia jego legendarium jako całości.

Opublikowane tu materiały, czyli niedokończony wczesny tekst Tolkiena Opowieść o Kullervo oraz dwa konspekty jego referatu O „Kalevali”, wygłoszonego na Uniwersytecie Oksfordzkim, a dotyczącego źródeł owej opowieści, zostały po raz pierwszy ogłoszone w 2010 r. w VII tomie „Tolkien Studies”. Jestem wdzięczna Tolkien Estate, czyli właścicielom praw autorskich do spuścizny literackiej pisarza, że pozwolili mi je tu przedrukować. Moje przypisy i komentarze zostały opublikowane za pozwoleniem wydawnictwa West Virginia University Press, a na przedruk eseju Tolkien,„Kalevala” i ”Opowieść o Kullervo” zezwoliło wydawnictwo Kent State University Press.

Podziękowania należą się też kilku osobom, bez pomocy których ta książka nigdy nie zostałaby wydana. Przede wszystkim dotyczy to Cathleen Blackburn, z którą jako pierwszą podzieliłam się myślą, że Opowieść o Kullervo powinna dotrzeć także do odbiorców spoza wąskiego grona czytelników naukowego czasopisma. Jestem wdzięczna Cathleen za uzyskanie odpowiednich pozwoleń od Tolkien Estate oraz publikującego dzieła J.R.R. Tolkiena wydawnictwa HarperCollins. Dziękuję obu tym instytucjom, że zaakceptowały moje przekonanie, iż Opowieść o Kullervo warta jest ponownego wydania jako samodzielne dzieło. Dziękuję także Chrisowi Smithowi, dyrektorowi wydawniczemu w HarperCollins zajmującemu się publikacjami pism Tolkiena, za pomoc, rady i wsparcie w pracy nad udostępnieniem Opowieści o Kullervo szerszemu kręgowi czytelników, na co ten tekst niewątpliwie zasługuje.

Verlyn Flieger

1 Wprawdzie obowiązujące w polszczyźnie zasady zalecają odmianę obcych imion męskich kończących się na -o, jeśli mają więcej niż dwie sylaby, jednak w tym wypadku świadomie postanowiliśmy się im nie podporządkować. Ośmielił nas fakt, że tego rodzaju odmiana fińskich imion z Kalevali, nawet jeśli się pojawia, nie jest stosowana konsekwentnie (np. nigdzie nie zetknęliśmy się z wersją tytułu *”Opowieść o Kullerwie/Kullervie”, a tak powinien on brzmieć zgodnie z regułami odmiany); w dodatku w języku fińskim nie ma wskazujących na płeć czy też rodzaj końcówek, toteż zastosowanie męskiej deklinacji byłoby w pewnym sensie wyborem arbitralnym. W konsekwencji podjętej przez nas decyzji takie imiona, jak Kullervo, Kalervo, Untamo itp., funkcjonują w tekście jako nieodmienne (przyp. red.).

Przedmowa

Jeżeli mamy w pełni docenić miejsce, jakie Opowieść o Kullervo zajmuje w całości spuścizny literackiej J.R.R. Tolkiena, powinniśmy na nią spojrzeć z kilku punktów widzenia. Jest to nie tylko najwcześniejsze opowiadanie Tolkiena, lecz także jego najwcześniejsza próba stworzenia dzieła tragicznego oraz najwcześniejsza prozatorska wyprawa na obszar mitotwórstwa. Opowieść o Kullervo stała się w ten sposób tekstem prekursorskim dla całego kanonu jego twórczości literackiej. Jeśli zaś przyjąć węższą perspektywę, okazuje się ona bardzo ważnym źródłem dzieła, które później zostało określone jako „mitologia dla Anglii”, czyli „Silmarillionu”2. Opowiedziana na nowo saga o nieszczęsnym Kullervo stanowi surowy materiał, który Tolkien rozwinął w jedną ze swych najbardziej przejmujących opowieści – historię o dzieciach Húrina. W szczególności zaś w postaci Kullervo tkwią zalążki najtragiczniejszego – według niektórych, jedynego tragicznego – bohatera twórczości Tolkiena, Túrina Turambara.

Z listów Tolkiena od dawna wiadomo, że kiedy jako uczeń odkrył Kalevalę, czy też „Krainę Bohaterów” – świeżo wówczas wydany zbiór pieśni, czyli run, niepiśmiennych fińskich chłopów – wywarło to ogromny wpływ na jego wyobraźnię i odcisnęło głęboki ślad na tworzonym przez niego legendarium. W liście z 1951 roku, w którym opisał swoją mitologię wydawcy Miltonowi Waldmanowi, Tolkien dał wyraz zatroskaniu, które zawsze odczuwał z powodu „ubóstwa” mitologii swego ojczystego kraju. Według pisarza Anglii brakowało „własnych opowieści”, porównywalnych z mitami innych krajów. Istnieją, jak pisał, „legendy greckie, celtyckie i romańskie, germańskie, skandynawskie” oraz (co specjalnie podkreślił) „fińskie”, o których stwierdził, że miały na niego „wielki wpływ” (J.R.R. Tolkien Listy, s. 239). Niewątpliwie wywarły na nim wielkie wrażenie; jak w 1944 roku wyznał swemu synowi Christopherowi (Listy, s. 148), przez to, że się nimi zajmował, o mało co nie oblał w 1913 roku egzaminu, tzw. Honour Moderations. „To on [język fiński] wszystko zapoczątkował”, jak napisał Tolkien w liście do W.H. Audena w 1955 roku (Listy, s. 350).

W czasie gdy Tolkien pracował nad swoją opowieścią, jej źródło, fiński epos Kalevala,dopiero od niedawna zajmowało miejsce w istniejącym zbiorze światowych mitologii. W przeciwieństwie do mitów greckich i rzymskich lub celtyckich czy germańskich, od długiego czasu funkcjonujących w literaturze, pieśni składające się na Kalevalę zostały zebrane i wydane dopiero w połowie XIX wieku przez Eliasa Lönnrota, lekarza z zawodu i folklorystę amatora. Pieśni różniły się tonem od całej reszty korpusu europejskich mitów – do tego stopnia, że doprowadziło to do przewartościowania i zmiany znaczeń takich terminów, jak „epika” i „mit”3. Niezależnie od owych różnic i przewartościowań, publikacja Kalevali silnie oddziałała na Finów. Od wieków żyli oni pod obcymi rządami: od XIII stulecia do 1809 roku ich kraj stanowił część Szwecji, a do 1917 roku – Rosji, której Szwecja przekazała sporą część terytorium Finlandii. Odkrycie rodzimej mitologii w epoce, w której zaczęto łączyć mit z ideą nacjonalizmu, dało Finom poczucie kulturowej niezależności i tożsamości narodowej, a także sprawiło, że Lönnrot stał się narodowym bohaterem. Kalevala wzmocniła kiełkujący fiński nacjonalizm i przyczyniła się do ogłoszenia przez Finlandię niepodległości od Rosji w 1917 roku. Wydaje się bardzo prawdopodobne, że wpływ Kalevali – jako „mitologii dla Finlandii”– na samych Finów zrobił na Tolkienie równie głębokie wrażenie jak same pieśni i że odegrało to istotną rolę w jego pragnieniu stworzenia „mitologii dla Anglii” – chociaż to, co opisał, było w istocie mitologią, którą mógłby „zadedykować” Anglii (Listy, s. 239). Fakt, że późniejsza postać Túrina Turambara z Tolkienowskiej mitologii w pewnym sensie zaabsorbowała cechy jego Kullervo, stanowi dowód nieustannego wpływu Kalevali na twórczość angielskiego pisarza.

Tolkien po raz pierwszy przeczytał Kalevalę w 1911 roku jako uczeń Szkoły Króla Edwarda w Birmingham. Był to przekład W. F. Kirby’ego z 1907 roku, który Tolkien uznał za niezadowalający, lecz sam materiał porównał do „wspaniałego wina” (Listy, s. 349). Zarówno stworzona przez niego opowieść, jak i towarzyszący jej referat O „Kalevali” wygłoszony w kolegium, a zachowany w postaci dwóch brudnopisów, dowodzą przepełnionego entuzjazmem dążenia Tolkiena, by opowiedzieć o smaku tego nowego wina, o jego świeżym, pogańskim bukiecie i „rozkosznej przesadzie” tych „szalonych […] niecywilizowanych i prymitywnych opowieści”. Owe niecywilizowane i prymitywne opowieści tak zapanowały nad jego wyobraźnią, że kiedy jesienią 1911 roku przeniósł się do Oksfordu, wypożyczył z biblioteki Kolegium Exeter książkę A Finnish Grammar [‘Gramatyka fińska’] C.N.E. Eliota, chcąc nauczyć się tego języka na tyle, by przeczytać oryginał. Próba zakończyła się niepowodzeniem i ze smutkiem musiał wyznać, że został „odrzucony z ciężkimi stratami”.

Tolkiena szczególnie ujęła postać, którą nazywał „nieszczęsnym Kullervo” (Listy, s. 350) – spośród bohaterów Kalevali najbardziej tragiczna. Tak bardzo pozostawał pod jej urokiem, że będąc na ostatnim roku studiów w Oksfordzie, napisał w październiku 1914 roku do swojej narzeczonej Edith Bratt, iż próbuje „przetworzyć jedną z opowieści – która jest naprawdę wspaniałą i bardzo tragiczną historią – na opowiadanie […] z dorzuconymi kawałkami poetyckimi” (Listy, s. 18). Była to Opowieść o Kullervo, której większa część powstała, o ile da się to ustalić, w latach 1912–1914 (Listy, s. 350), prawie na pewno przed powołaniem Tolkiena do wojska i jego wyjazdem w 1916 roku na front do Francji. Owo datowanie jest jednak problematyczne. Sam Tolkien podał rok 1912; badacze Wayne Hammond i Christina Scull skłaniają się ku dacie 1914, także John Garth sytuuje powstanie Opowieści o Kullervo pod koniec tego właśnie roku. Na stronie tytułowej rękopisu (il. 1) widnieje w nawiasie data „(1916)” napisana ręką Christophera Tolkiena, ale została ona tam umieszczona prawie czterdzieści lat po fakcie, widnieje ona bowiem na odwrotnej stronie listu pochwalnego dla Tolkiena z okazji otrzymania przez niego w 1954 roku doktoratu honoris causa Narodowego Uniwersytetu Irlandzkiego. Podaje ją w wątpliwość umieszczony poniżej dopisek ołówkiem: „HC [Humphrey Carpenter] mówi 1914”. Uwaga ta została zapewne zrobiona w czasie, kiedy Carpenter pracował nad swoją opublikowaną w 1977 roku biografią Tolkiena.

Często trudno jest precyzyjnie określić datę powstania danego dzieła, ponieważ na ogół praca nad jego tworzeniem zajmuje dłuższy okres, od pierwszego pomysłu do ostatecznej wersji, i przez cały ten czas może być przerywana, wznawiana i korygowana. Dysponując tylko tymi rękopiśmiennymi dowodami, które mamy w chwili obecnej, nie możemy określić czasu pracy Tolkiena nad Opowieścią o Kullervo – od pierwszego pomysłu do jej przerwania – bardziej precyzyjnie niż na lata 1912–1916. Jest rzeczą dość pewną, że nie rozpoczął on pracy przed przeczytaniem Kalevali w 1911 roku i z dużym prawdopodobieństwem można stwierdzić, że jej nie kontynuował po tym, jak w czerwcu 1916 roku został wysłany na front do Francji. Uwaga Tolkiena w liście do Edith świadczyłaby o tym, że „wszystko zapoczątkowały” w równej mierze tragizm opowieści i jej mityczny charakter. Obie cechy okazały się tak bardzo pociągające, że odczuł potrzebę opowiedzenia jej od nowa.

Oprócz faktu, że wyraźnie wpłynęła na historię Túrina Turambara, Opowieść o Kullervo jest godna uwagi także ze względu na sposób, w jaki zapowiada różne style narracji przyszłych tekstów Tolkiena, będąc demonstracją kilku gatunków czy też kategorii albo form – opowiadania, tragedii, przetworzonego mitu, poezji, prozy – które stosował w późniejszej twórczości. Jest to równocześnie opowiadanie, tragedia, mit, mieszanka prozy i poezji, jednakże – co raczej nie dziwi w tak wczesnym dziele – wszystkie te formy istnieją tu w zarodku i nie są w pełni zrealizowane. Pod każdym z tych względów Opowieść o Kullervo odbiega nieco od kanonu pisarstwa Tolkiena. Jako opowiadanie może być porównywana z jego późniejszymi opowiadaniami: Łazikantym, Liściem, dziełem Niggle’a, Rudym Dżilem i jego psem oraz Kowalem z Podlesia Większego, jako opowiedziany na nowo mit staje obok Legendy o Sigurdzie i Gudrún oraz Upadku króla Artura, jako mieszanka prozy i poezji przypomina podobne połączenie w arcydziele Tolkiena, Władcy Pierścieni. Istnieje też pole do porównań pod względem stylistycznym, ponieważ „kawałki poetyckie” często gładko przechodzą w zrytmizowaną prozę, która przypomina syntezę poezji i prozy w wypowiedziach Toma Bombadila.

Jednakże porównania na tym się kończą, jako że pod innymi względami Opowieść o Kullervo ma niewiele wspólnego z większością wymienionych wyżej utworów. Jedynie Legenda o Sigurdzie i Gudrún oddaje tę pogańską atmosferę, która stanowi istotę Opowieści o Kullervo, a w Upadku króla Artura dochodzi do głosu podobne poczucie nieuchronności losu. Łazikanty – chociaż, jak to niedawno zauważono, zawiera wyraźne podobieństwa do mitycznych irlandzkich imramma, czyli opowieści o podróżach4 – powstał jako opowiastka dla dzieci i zasadniczo nią pozostaje. Opowiadanie Liść, dzieło Niggle’a,którego umieszczona we współczesności akcja rozgrywa się w nieokreślonym dokładnie czasie i niesprecyzowanym miejscu, będącym jednak wyraźnie Anglią znaną Tolkienowi, to przypowieść o podróży duszy i najbardziej alegoryczny ze wszystkich jego utworów. Rudy Dżil i jego pies to żartobliwie satyryczne naśladowanie podania ludowego zawierające wiele uczonych dowcipów oraz aktualnych aluzji do Oksfordu z czasów Tolkiena. Kowal z Podlesia Większego jest baśnią w stanie czystym, pod względem artystycznym najbardziej spójnym spośród wszystkich krótkich utworów pisarza. W przeciwieństwie do nich, Opowieść o Kullervo zdecydowanie nie jest przeznaczona dla dzieci, nie jest ani żartobliwa czy satyryczna, ani alegoryczna, nie ma w niej też tej czarodziejskiej atmosfery, którą Tolkien uważał za podstawową cechę baśni. To nieodparcie mroczna, złowróżbna i tragiczna opowieść o krwawej waśni, morderstwie, maltretowaniu dzieci, zemście, kazirodztwie i samobójstwie, tak odmienna w tonie i treści od innych krótkich utworów Tolkiena, że stanowi niemal oddzielną kategorię.

Jako tragedia Opowieść o Kullervo w dużej mierze odpowiada Arystotelesowskiemu przepisowi na tragedię: jest tu katastrofa, czyli klęska, którą ponosi bohater; perypetia, czyli odmiana losu, w trakcie której bohater nieumyślnie doprowadza do skutku przeciwnego do zamierzonego; oraz anagnoryzm, czyli rozpoznanie, kiedy to bohater przechodzi od niewiedzy do samowiedzy. Klasycznym przykładem jest tu Edyp, którego dramat Sofokles umieścił w quasi-historycznym miejscu i czasie – w Tebach w IV wieku p.n.e. Przykładami z Tolkienowskiego fikcyjnego Śródziemia są Túrin Turambar, wzorowany na postaci Kullervo, oraz bohater o najmniejszym z pozoru potencjale tragicznym, Frodo Baggins, którego podróż i emocjonalna trajektoria, prowadząca z Bag End do Góry Przeznaczenia, spełnia wszystkie warunki norm Arystotelesa, umieszczonych w szerszym kontekście Śródziemia, podobnie jak to się dzieje w wypadku Túrina. W przeciwieństwie do ich dziejów, Opowieść o Kullervo jest w dużej mierze ahistoryczna i tworzy własny, samowystarczalny świat, którego jedynym czasem jest czas, „gdy magia była jeszcze młoda”.

Jako najwcześniejsza próba Tolkiena przystosowania istniejącego mitu do jego własnych celów, Opowieść o Kullervo pasuje do jego dwóch innych, dojrzalszych utworów, obu datowanych z dużą dozą prawdopodobieństwa na 20.–30. lata XX wieku. Są to: Legenda o Sigurdzie i Gudrún, wierszowana wersja opowieści o Völsungach z islandzkiej Eddy poetyckiej, oraz Upadek króla Artura, synteza i przeróbka na aliteracyjny wiersz we współczesnej angielszczyźnie dwóch średnioangielskich poematów arturiańskich. Podobnie jak jego Artur i Sigurd, Kullervo Tolkiena jest najnowszą wersją mitycznej postaci, która miała wiele wcieleń. Cechy Kullervo można odnaleźć u wczesnośredniowiecznego irlandzkiego Amlodhiego, skandynawskiego Amletha z dwunastowiecznego dzieła Saksa Gramatyka Gesta Danorum, oraz u bardziej współczesnego Szekspirowskiego renesansowego księcia Hamleta. Szereg ten osiąga kulminację w postaci Kullervo z Kalevali, na którym najbardziej bezpośrednio Tolkien wzorował swojego bohatera. Mimo to opowieść ta nie pasuje najlepiej do jego późniejszych adaptacji mitów. Po pierwsze, zarówno Kalevala, jak Kullervo Tolkiena są znacznie mniej znani niż Sigurd i Artur. Wielu czytelników, znających te dwie ostatnie postacie, w Opowieści o Kullervo styka się z tym nieprawdopodobnym bohaterem po raz pierwszy. Dlatego też wersja Tolkiena nie jest dla nich niczym obciążona i może być czytana bez z góry przyjętych założeń. Jeżeli ktoś już rozpozna w Tolkienowskim Kullervo Szekspirowskiego księcia Hamleta, to będą to bardzo nieliczni czytelnicy, chociaż bystre oko może dostrzec w bezwzględnym i pozbawionym skrupułów wuju Kullervo, Untamo, zalążek bezwzględnego i pozbawionego skrupułów wuja Hamleta, Klaudiusza.

Jeśli chodzi o formę narracji, Kullervo Tolkiena plasuje się pomiędzy jego opowiadaniami i długimi poematami, jako że stanowi mieszaninę prozy i poezji, gdzie długie fragmenty poezji są umieszczone w tekście napisanym stylizowaną prozą. Podobnie jak Sigurd i Gudrún jest to opowieść o miłości, nad którą wisi nieunikniony los, niedający bohaterom nadziei na wybawienie, a podobnie jak Upadek króla Artura opowiada ona o tym, jak ten nieuchronny los miesza się z ludzkimi decyzjami, które bezlitośnie determinują życie człowieka. Także, podobnie jak Upadek króla Artura, lecz w przeciwieństwie do Sigurda i Gudrún, opowieść jest niedokończona i urywa się przed ostatnimi, kulminacyjnymi scenami, które pozostają jedynie naszkicowane w streszczeniu planowanej fabuły i notatkach. Taka niedokończona postać jest, niestety, typowa dla wielu dzieł Tolkiena. Kiedy umarł, więcej było opowieści z jego „Silmarillionu”, które pozostały nieukończone, niż tych doprowadzonych do ostatecznego kształtu za jego życia. Pomijając to negatywne stwierdzenie, Opowieść o Kullervo zasługiwałaby na miejsce w kontinuum dzieł Tolkiena ze względu na wszystkie wymienione wyżej powody.

Lecz, jak już zostało wspomniane, największe znaczenie Opowieści o Kullervo zawiera się w tym, że jest to wstęp do Dzieci Húrina, jednej z podstawowych historii jego legendarium, a główna postać Opowieści jest wyraźnym pierwowzorem bohatera tej ostatniej, Túrina Turambara. Tolkien wspominał także o innych źródłach inspiracji przy tworzeniu postaci Túrina, takich jak islandzka Edda, z której zapożyczył epizod z zabiciem przez niego smoka, oraz Edyp Sofoklesa, który (jak zostało powiedziane wyżej), podobnie jak Túrin, jest bohaterem tragicznym, poszukującym swojej tożsamości. Niemniej nie jest przesadne stwierdzenie, że bez Kalevali nie byłoby Opowieści o Kullervo, a bez Opowieści o Kullervo nie byłoby Túrina. Z pewnością bez opowieści o Túrinie wymyślonej mitologii Tolkiena brakowałoby sporej dozy jej tragicznej siły, a także najbardziej poza Władcą Pierścieni poruszającej fabuły. W Opowieści o Kullervo możemy także rozpoznać, choć już nie tak bezpośrednio, kilka powtarzających się motywów, obecnych w utworach Tolkiena: dziecko pozbawione ojca, nadprzyrodzony pomocnik, pełna napięcia relacja między wujem i siostrzeńcem oraz ceniona pamiątka rodowa czy talizman. Chociaż motywy te są przeniesione do nowych okoliczności narracyjnych i czasami rozwijane w całkowicie odmiennych kierunkach, tworzą kontinuum rozciągające się od Opowieści o Kullervo, najwcześniejszego poważnego dzieła pisarza, aż po Kowala z Podlesia Większego, ostatnią opowieść Tolkiena opublikowaną za jego życia.

We wspomnianym liście do Waldmana Tolkien wyraził nadzieję, że jego wymyślony mit zostawi „pole do popisu innym umysłom i dłoniom, które parają się malarstwem, muzyką i dramatem” (Listy, s. 240). Mógł tu mieć na myśli także Kalevalę, ponieważ jego wzmianka o malarstwie i muzyce oraz polu do popisu dla innych dłoni równie dobrze może stanowić aluzję do przekładania materiału z Kalevali na malarstwo i muzykę przez innych artystów, którzy się nią inspirowali. Dwa wybitne przykłady to kompozytor muzyki poważnej Jan Sibelius oraz malarz Akseli Gallen-Kallela, dwaj najsławniejsi fińscy artyści końca XIX i początku XX wieku. Komponując suity orkiestrowe Lemminkainen i Tapiola oraz dłuższą suitę Kullervo na chór i orkiestrę, Sibelius czerpał z Kalevali, zamieniając mit w muzykę. Akseli Gallen-Kallela, najwybitniejszy nowożytny malarz fiński, namalował wiele scen z Kalevali, w tym cztery przedstawiające najważniejsze chwile z życia Kullervo. Popularność tej postaci i jej atrakcyjność dla artystów sugeruje, że można się w niej dopatrywać folklorystycznego ucieleśnienia gwałtowności i burzliwej irracjonalności równie burzliwej ery nowożytnej. Nie trzeba wielkiej wyobraźni, by ujrzeć Tolkienowskiego Túrina Turambara jako wytwór tej samej targanej wojnami epoki, jako bohatera tego samego rodzaju ukazanego w podobnym świetle.

Narracja w opowieści Tolkiena odwołuje się wiernie do fabuły Kalevali przedstawionej w runach od 31 do 36, które w przekładzie Kirby’ego noszą kolejno tytuły: „Untamo i Kullervo”, „Kullervo i żona Ilmarinena”, „Śmierć żony Ilmarinena”, „Kullervo i jego rodzice”, „Kullervo i jego siostra” oraz „Śmierć Kullervo”. Mimo że przedstawione jako oddzielne utwory, tworzą one koherentną (choć może nie zawsze całkowicie spójną), w sposób uporządkowany opowiedzianą historię fatalnej kłótni między braćmi, w wyniku której jeden z nich ginie, a drugi, jego zabójca, zostaje opiekunem Kullervo, nowo narodzonego syna martwego brata. Maltretowany zarówno przez opiekuna, jak i przez jego żonę, chłopiec ma nieszczęśliwe dzieciństwo, podczas którego trzykrotnie udaje mu się ujść śmierci z ich rąk – przez utonięcie, spalenie i powieszenie. Ostatecznie mści się na obojgu opiekunach, lecz później ginie z własnej ręki, odkrywszy, że nieumyślnie dopuścił się kazirodztwa z siostrą, której tożsamość zbyt późno rozpoznał. W ujęciu Tolkiena historia ta zyskuje głębię, dłużej utrzymuje czytelnika w napięciu, wzbogaca się o aspekt psychologiczny i element tajemniczości, a charaktery bohaterów są przedstawione w sposób bardziej rozwinięty. Jednocześnie zostają zachowane pogańskie i prymitywne cechy opowieści, które tak pociągały Tolkiena w Kalevali.

Opowieść o Kullervo istnieje w pojedynczym rękopisie o sygnaturze Biblioteki Bodlejskiej MS Tolkien B 64/6. Jest to czytelny brudnopis z wieloma przekreśleniami, dopiskami umieszczonymi na marginesach lub nad poszczególnymi wersami, poprawkami i korektami. Tekst jest napisany ołówkiem, dwustronnie, na 13 kartkach papieru kancelaryjnego o wymiarach 216 x 343 mm, ponumerowanych po jednej stronie. Główny tekst urywa się nagle, mniej więcej w trzech czwartych opowiadanej historii, w połowie pierwszej strony kartki numer 13. Niżej na tej samej stronie widnieją notatki i szkice dalszego ciągu (il. 4 i 5), które wypełniają wolne miejsca i są kontynuowane na następnej stronie u góry. Do tego dochodzi kilka luźnych kartek różnych rozmiarów, na których najwyraźniej zapisano wstępne zarysy fabuły, notatki, listę imion (il. 3), spis rymujących się wyrazów i kilka szkiców długiego ustępu poetyckiego „Now a man in sooth I deem me” [‘Zaiste za męża się mam‘]. Jeśli, co wydaje się prawdopodobne, tekst o sygnaturze MS Tolkien B 64/6 zawiera najwcześniejszy i – wyjąwszy strony z notatkami – jedyny brudnopis opowieści, to poprawki poczynione przez Tolkiena na tym rękopisie trzeba uznać za ostateczne.

Nie zmieniałam dziwacznego czasami użycia słów przez Tolkiena ani jego często zawiłej składni, jedynie w kilku miejscach wprowadziłam znaki interpunkcyjne konieczne dla uściślenia znaczenia. W nawiasach prostokątnych podałam domyślne odczytania oraz słowa lub fragmenty słów pominięte w rękopisie, a wstawione przeze mnie dla jasności tekstu. Znaków diakrytycznych umieszczanych nad samogłoską – głównie znaku długości, lecz sporadycznie także krótkości oraz umlautu – Tolkien używa niekonsekwentnie, co mogło wynikać raczej z pośpiesznego zapisu niż z celowego ich pomijania. Opuściłam wykreślone słowa i wersy, uczyniłam jednak cztery wyjątki dla zwrotów lub zdań przekreślonych w rękopisie, ale zachowanych jako szczególnie ciekawe dla rozwoju opowieści i ujętych przeze mnie w nawiasy klamrowe. Trzy z wykreślonych fragmentów świadczą o długotrwałym zainteresowaniu Tolkiena istotą magii i światem nadprzyrodzonym. Dwa z nich pojawiają się w pierwszym zdaniu opowieści. Są to sformułowania: 1) „of magic long ago” [‘magii dawno temu‘] oraz: 2) „when magic was yet new” [‘gdy magia była jeszcze młoda‘]. Trzeci fragment to dłuższe zdanie zaczynające się od słów „and to Kullervo he [Musti] gave three hairs” [‘i dał [Musti] Kullervo trzy włoski‘], które odnosi się do nadprzyrodzonego pomocnika Kullervo, psa Mustiego, i także dowodzi obecności magii w tej opowieści. Czwarty fragment pojawia się dalej i być może ma charakter autobiograficzny: „I was small and lost my mother” [‘byłem mały, straciłem matkę’].

Wolałam nie przerywać ciągłości tekstu (i nie rozpraszać uwagi czytelnika) numerami przypisów, dlatego dopiero po tekście, w części „Przypisy i komentarz”, wyjaśniam rozmaite terminy oraz ich zastosowanie, podaję źródła i wskazuję na związek opowieści z jej pierwowzorem. Znajdują się tam również wstępne notatki Tolkiena dotyczące rozwoju akcji, co pozwala czytelnikowi dostrzec zmiany w tekście i śledzić tok myśli autora.

Niniejsze wydanie opowieści Tolkiena wraz z brudnopisami jego szkicu O „Kalevali” pozwala zarówno badaczom i krytykom, jak i zwykłym czytelnikom zapoznać się ze „wspaniałą i bardzo tragiczną” historią, o której Tolkien pisał do Edith w 1914 roku i która miała tak znaczny udział w powstaniu jego legendarium. Można żywić nadzieję, że uznają oni tę publikację za interesujące i cenne uzupełnienie literackiego dzieła Tolkiena.

O imionach

Opowieść tę trzeba traktować jako dzieło w stadium powstawania, nie tylko dlatego, że nie została ukończona, ale również z tego powodu, że gdy Tolkien zaczął ją pisać, używał imion zaczerpniętych z Kalevali, lecz w trakcie pracy zastępował je imionami i przydomkami przez siebie wymyślonymi. Niezmienione pozostawił jedynie imiona głównych postaci, a mianowicie Kalervo, zamordowanego brata, jego syna Kullervo oraz Untamo, zbrodniczego brata pierwszego, a wuja drugiego z nich, jednakże nawet im nadawał rozmaite przydomki niepojawiające się w Kalevali. Nie stosował konsekwentnie tej zasady i czasami wracał do wcześniej porzuconego imienia lub zapominał je zmienić. Najistotniejsza jest zmiana imienia Ilmarinen, które nosi w Kalevali kowal, na imię Āsemo, jak nazywa Tolkien tę samą postać we własnej opowieści. Obszerniejsze omówienie etymologii tego imienia można znaleźć pod hasłem „Āsemo” w rozdziale „Przypisy i komentarz”. Tolkien eksperymentował też z alternatywnymi imionami dla Wanōny, siostry Kullervo, i jego psa Mustiego.

Carl Hostetter zwrócił moją uwagę na to, że niektóre z wymyślonych imion w Opowieści o Kullervo zapowiadają najwcześniejsze próby Tolkiena dotyczące qenyi, stworzonego przez niego prajęzyka. Do pojawiających się w opowieści imion o qenejskim brzmieniu należą imiona bóstwa: Ilu, Ilukko oraz Ilwinti, wyraźnie kojarzące się z imieniem Ilúvatar, które nosi boska istota z „Silmarillionu”. Kampa, przydomek Kalervo, pojawia się we wczesnej wersji qenyi jako imię jednej z pierwszych postaci z legendarium Tolkiena, Earendela, i znaczy ‘Skoczek’. Nazwa geograficzna Kēme lub Kĕmĕnūme, w opowieści Tolkiena wyjaśniana jako „Wielka Kraina, Rosja” (zob. il. 2), w qenyi oznacza ‘ziemię’, ‘glebę’. Nazwa Telea (określenie Karelii) przywołuje na myśl Telerich, w „Silmarillionie” jedną z trzech grup elfów, którzy udali się ze Śródziemia do Valinoru. Manalome, Manatomi, Manoini, nazwy oznaczające ‘niebo’, ‘niebiosa’, przypominają qenejskie imię Mana/Manwë, które nosi przywódca Valarów, półbogów z „Silmarillionu”. Istnieją poszlaki wskazujące na chronologiczny związek między imionami z Opowieści o Kullervo i narodzinami qenyi, na co najwcześniejsze dowody można znaleźć w leksykonie qenyi.

Szersze ujęcie kwestii rozwoju qenyi czytelnik może znaleźć w tekście Tolkiena „Qenyaqetsa: The Qenya Phonology and Lexicon” [‘Qenyaqetsa: fonologia i leksykon qenyi’], napisanym najprawdopodobniej w latach 1915–1916, a opublikowanym w czasopiśmie „Parma Eldalamberon”, XII, 1998.

Verlyn Flieger

2 Wśród badaczy dzieł Tolkiena przyjęło się w ten sposób oznaczać zbiór tekstów tworzących tzw. legendarium, nigdy nieopublikowane jako jedno dzieło; ten sam tytuł pisany kursywą wskazuje na wydaną w 1977 roku książkę składającą się z fragmentów owego legendarium wybranych przez Christophera Tolkiena (przyp. tłum.).

3 Wywołało to również pytania o rolę, jaką zbieracz odgrywa w wybieraniu, redagowaniu i przedstawianiu zebranego materiału, prowadząc do oskarżeń (zwłaszcza w wypadku Kalevali) o fałszowanie folkloru. To jednak temat wymagający osobnego omówienia. Kiedy Tolkien po raz pierwszy czytał Kalevalę, wszyscy zakładali jej autentyczność.

4 Zob. artykuł Kris Swank „The Irish Otherworld Voyage of Roverandom” [‘Irlandzka nieziemska podróż Łazikantego’], „Tolkien Studies”, t. XII, planowana publikacja w 2015 roku.

OPOWIEŚĆ O KULLERVO

1. Strona tytułowa manuskryptu napisana przez Christophera Tolkiena [MS Tolkien B 64/6, karta 1 recto].

2. Pierwsza strona manuskryptu [MS Tolkien B 64/6, karta 2 recto].

The Story of Honto Taltewenlen

The Story of Kullervo

(Kalervonpoika)

In the days {of magic long ago} {when magic was yet new}, a swan nurtured her brood of cygnets by the banks of a smooth river in the reedy marshland of Sutse. One day as she was sailing among the sedge-fenced pools with her trail of younglings following, an eagle swooped from heaven and flying high bore off one of her children to Telea: on the second day a mighty hawk robbed her of yet another and bore it to Kemenūme. Now that nursling that was brought to Kemenūme waxed and became a trader and cometh not into this sad tale: but that one whom the hawk brought to Telea he it is whom men name Kalervō: while a third of the nurslings that remained behind men speak oft of him and name him Untamō the Evil, and a fell sorcerer and man of power did he become.

And Kalervo dwelt beside the rivers of fish and had thence much sport and good meat, and to him had his wife borne in years past both a son and a daughter and was even now again nigh to childbirth. And in those days did Kalervo’s lands border on the confines of the dismal realm of his mighty brother Untamo; who coveted his pleasant river lands and its plentiful fish.

So coming he set nets in Kalervo’s fish waters and robbed Kalervo of his angling and brought him great grief. And bitterness arose between the brothers, first that and at last open war. After a fight upon the river banks in which neither might overcome the other, Untamo returned to his grim homestead and sat in evil brooding, weaving (in his fingers) a design of wrath and vengeance.

He caused his mighty cattle to break into Kalervo’s pas- tures and drive his sheep away and devour their fodder. Then Kalervo let forth his black hound Musti to devour them. Untamo then in ire mustered his men and gave them weapons; armed his henchmen and slave lads with axe and sword and marched to battle, even to ill strife against his very brother.

And the wife of Kalervoinen sitting nigh to the window of the homestead descried a scurry arising of the smoke army in the distance, and she spake to Kalervo saying, ‘Husband, lo, an ill reek ariseth yonder: come hither to me. Is it smoke I see or but a thick[?] gloomy cloud that passeth swift: but now hovers on the borders of the cornfields just yonder by the new-made pathway?’

Then said Kalervo in heavy mood, ‘Yonder, wife, is no reek of autumn smoke nor any passing gloom, but I fear me a cloud that goeth nowise swiftly nor before it has harmed my house and folk in evil storm.’ Then there came into the view of both Untamo’s assemblage and ahead could they see the numbers and their strength and their gay scarlet raiment. Steel shimmered there and at their belts were their swords hanging and in their hands their stout axes gleaming and neath their caps their ill faces lowering: for ever did Untamoinen gather to him cruel and worthless carles.

And Kalervo’s men were out and about the farm lands so seizing axe and shield he rushed alone on his foes and was soon slain even in his own yard nigh to the cowbyre in the autumn-sun of his own fair harvest-tide by the weight of the numbers of foemen. Evilly Untamoinen wrought with his brother’s body before his wife’s eyes and foully entreated his folk and lands. His wild men slew all whom they found both man and beast, sparing only Kalervo’s wife and her two children and sparing them thus only to bondage in his gloomy halls of Untola.

Bitterness then entered the heart of that mother, for Kalervo had she dearly loved and dear been to him and she dwelt in the halls of Untamo caring naught for anything in the sunlit world: and in due time bore amidst her sorrow Kalervo’s babes: a man-child and a maid-child at one birth. Of great strength was the one and of great fairness the other even at birth and dear to one another from their first hours: but their mother’s heart was dead within, nor did she reck aught of their goodliness nor did it gladden her grief or do better than recall the old days in their home- stead of the smooth river and the fish waters among the reeds and the thought of the dead Kalervo their father, and she named the boy Kullervo, or ‘wrath’, and his daughter Wanōna, or ‘weeping’. And Untamo spared the children for he thought they would wax to lusty servants and he could have them do his bidding and tend his body nor pay them the wages he paid the other uncouth carles. But for lack of their mother’s care the children were reared in crooked fashion, for ill cradle rocking meted to infants by fosterers in thralldom: and bitterness do they suck from breasts of those that bore them not.

The strength of Kullervo unsoftened turned to untame- able will that would forego naught of his desire and was resentful of all injury. And a wild lone-faring maiden did Wanōna grow, straying in the grim woods of Untola so soon as she could stand – and early was that, for wondrous were these children and but one generation from the men of magic. And Kullervo was like to her: an ill child he ever was to handle till came the day that in wrath he rent in pieces his swaddling clothes and kicked with his strength his linden cradle to splinters – but men said that it seemed he would prosper and make a man of might and Untamo was glad, for him thought he would have in Kullervo one day a warrior of strength and a henchman of great stoutness. Nor did this seem unlike, for at the third month did Kullervo, not yet more than knee-high, stand up and spake in this wise on a sudden to his mother who was grieving still in her yet green anguish. ‘O my mother, o my dearest why grievest thou thus?’ And his mother spake unto him telling him the dastard tale of the Death of Kalervo in his own homestead and how all he had earned was ravished and slain by his brother Untamo and his underlings, and nought spared or saved but his great hound Musti who had returned from the fields to find his master slain and his mistress and her children in bondage, and had followed their exile steps to the blue woods round Untamo’s halls where now he dwelt a wild life for fear of Untamo’s henchmen and ever and anon slaughtered a sheep and often at the night could his baying be heard: and Untamo’s underlings said it was the hound of Tuoni Lord of Death though it was not so.

All this she told him and gave him a great knife curious wrought that Kalervo had worn ever at his belt if he fared afield, a blade of marvellous keenness made in his dim days, and she had caught it from the wall in the hope to aid her dear one.

Thereat she returned to her grief and Kullervo cried aloud, ‘By my father’s knife when I am bigger and my body waxeth stronger then will I avenge his slaughter and atone for the tears of thee my mother who bore me.’ And these words he never said again but that once, but that once did Untamo overhear. And for wrath and fear he trembled and said he will bring my race in ruin for Kalervo is reborn in him.

And therewith he devised all manner of evil for the boy (for so already did the babe appear, so sudden and so marvellous was his growth in form and strength) and only his twin sister the fair maid Wanōna (for so already did she appear, so great and wondrous was her growth in form and beauty) had compassion on him and was his companion in their wandering the blue woods: for their elder brother and sister (of which the tale told before), though they had been born in freedom and looked on their father’s face, were more like unto thralls than those orphans born in bondage, and knuckled under to Untamo and did all his evil bidding nor in anything recked to comfort their mother who had nurtured them in the rich days by the river.

And wandering in the woods a year and a month after their father Kalervo was slain these two wild children fell in with Musti the Hound. Of Musti did Kullervo learn many things concerning his father and Untamo and of things darker and dimmer and farther back even perhaps before their magic days and even before men as yet had netted fish in Tuoni the marshland.

Now Musti was the wisest of hounds: nor do men say ever aught of where or when he was whelped but ever speak of him as a dog of fell might and strength and of great knowledge, and Musti had kinship and fellowship with the things of the wild, and knew the secret of the changing of skin and could appear as wolf or bear or as cattle great or small and could much other magic besides. And on the night of which it is told, the hound warned them of the evil of Untamo’s mind and that he desired nothing so much as Kullervo’s death {and to Kullervo he gave three hairs from his coat, and said, ‘Kullervo Kalervanpoika, if ever you are in danger from Untamo take one of these and cry ‘Musti O! Musti may thy magic aid me now’, then wilt thou find a marvellous aid in thy distress.’}

And next day Untamo had Kullervo seized and crushed into a barrel and flung into the waters of a rushing torrent – that seemed like to be the waters of Tuoni the River of Death to the boy: but when they looked out upon the river three days after, he had freed himself from the barrel and was sitting upon the waves fishing with a rod of copper with a silken line for fish, and he ever remained from that day a mighty catcher of fish. Now this was the magic of Musti.

And again did Untamo seek Kullervo’s destruction and sent his servants to the woodland where they gathered mighty birch trees and pine trees from which the pitch was oozing, pine trees with their thousand needles. And sledge- fuls of bark did they draw together, and great ash trees a [hundred] fathoms in length: for lofty in sooth were the woods of gloomy Untola. And all this they heaped for the burning of Kullervo.

They kindled the flame beneath the wood and the great bale-fire crackled and the smell of logs and acrid smoke choked them wondrously and then the whole blazed up in red heat and thereat they thrust Kullervo in the midst and the fire burned for two days and a third day and then sat there the boy knee-deep in ashes and up to his elbows in embers and a silver coal-rake he held in his hand and gathered the hottest fragments around him and himself was unsinged.

Untamo then in blind rage seeing that all his sorcery availed nought had him hanged shamefully on a tree. And there the child of his brother Kalervo dangled high from a great oak for two nights and a third night and then Untamo sent at dawn to see whether Kullervo was dead upon the gallows or no. And his servant returned in fear: and such were his words: ‘Lord, Kullervo has in no wise perished as yet: nor is dead upon the gallows, but in his hand he holdeth a great knife and has scored wondrous things therewith upon the tree and all its bark is covered with carvings wherein chiefly is to be seen a great fish (now this was Kalervo’s sign of old) and wolves and bears and a huge hound such as might even be one of the great pack of Tuoni.’

Now this magic that had saved Kullervo’s life was the last hair of Musti: and the knife was the great knife Sikki: his father’s, which his mother had given to him: and there- after Kullervo treasured the knife Sikki beyond all silver and gold.

Untamoinen felt afraid and yielded perforce to the great magic that guarded the boy, and sent him to become a slave and to labour for him without pay and but scant fostering: indeed often would he have starved but for Wanōna who, though Unti treated her scarcely better, spared her brother much from her little. No compassion for these twins did their elder brother and sister show, but sought rather by subservience to Unti to get easier life for themselves: and a great resentment did Kullervo store up for himself and daily he grew more morose and violent and to no one did he speak gently but to Wanōna and not seldom was he short with her.

So when Kullervo had waxed taller and stronger Untamo sent for him and spake thus: ‘In my house I have retained you and meted wages to you as methought thy bearing merited – food for thy belly or a buffet for thy ear: now must thou labour and thrall or servant work will I appoint for you. Go now, make me a clearing in the near thicket of the Blue Forest. Go now.’ And Kuli went. But he was not ill pleased, for though but of two years he deemed himself grown to manhood in that now he had an axe set in hand, and he sang as he fared him to the woodlands.

Song of Sākehonto in the woodland:

Now a man in sooth I deem me

Though mine ages have seen few summers

And this springtime in the woodlands

Still is new to me and lovely.

Nobler am I now than erstwhile

And the strength of five within me

And the valour of my father

In the springtime in the woodlands

Swells within me Sākehonto.

O mine axe my dearest brother –

Such an axe as fits a chieftain,

Lo we go to fell the birch-trees

And to hew their white shafts slender:

For I ground thee in the morning

And at even wrought a handle;

And thy blade shall smite the tree-boles

And the wooded mountains waken

And the timber crash to earthward

In the springtime in the woodland

Neath thy stroke mine iron brother.

And thus fared Sākehonto to the forest slashing at all that he saw to the right or to the left, him recking little of the wrack, and a great tree-swathe lay behind him for great was his strength. Then came he to a dense part of the forest high up on one of the slopes of the mountains of gloom, nor was he afraid for he had affinity with wild things and Mauri’s [Musti’s] magic was about him, and there he chose out the mightiest trees and hewed them, felling the stout at one blow and the weaker at a half. And when seven mighty trees lay before him on a sudden he cast his axe from him that it half cleft through a great oak that groaned thereat: but the axe held there quivering.

But Sāki shouted, ‘May Tanto Lord of Hell do such labour and send Lempo for the timbers fashioning.’

And he sang:

Let no sapling sprout here ever

Nor the blades of grass stand greening

While the mighty earth endureth

Or the golden moon is shining

And its rays come filtering dimly

Through the boughs of Saki’s forest.

Now the seed to earth hath fallen

And the young corn shooteth upward

And its tender leaf unfoldeth

Till the stalks do form upon it.

May it never come to earing

Nor its yellow head droop ripely

In this clearing in the forest

In the woods of Sākehonto.

And within a while came forth Ūlto to gaze about him to learn how the son of Kampo his slave had made a clearing in the forest but he found no clearing but rather a ruthless hacking here and there and a spoilage of the best of trees: and thereon he reflected saying, ‘For such labour is the knave unsuited, for he has spoiled the best timber and now I know not whither to send him or to what I may set him.’

But he bethought him and sent the boy to make a fencing betwixt some of his fields and the wild; and to this work then Honto set out but he gathered the mightiest of the trees he had felled and hewed thereto others: firs and lofty pines from blue Puhōsa and used them as fence stakes; and these he bound securely with rowans and wattled: and made the tree-wall continuous without break or gap: nor did he set a gate within it nor leave an opening or chink but said to himself grimly, ‘He who may not soar swift aloft like a bird nor burrow like the wild things may never pass across it or pierce through Honto’s fence work.’

But this over-stout fence displeased Ūlto and he chid his slave of war for the fence stood without gate or gap beneath, without chink or crevice resting on the wide earth beneath and towering amongst Ukko’s clouds above.

For this do men call a lofty Pine ridge ‘Sāri’s hedge’.

‘For such labour,’ said Ūlto, ‘art thou unsuited: nor know I to what I may set thee, but get thee hence, there is rye for threshing ready.’ So Sāri got him to the threshing in wrath and threshed the rye to powder and chaff that the winds of Wenwe took it and blew as a dust in Ūlto’s eyes, whereat he was wroth and Sāri fled. And his mother was feared for that and Wanōna wept, but his brother and elder sister chid them for they said that Sāri did nought but make Ūlto angered and of that anger’s ill did they all have a share while Sāri skulked the woodlands. Thereat was Sāri’s heart bitter, and Ūlto spake of selling as a bond slave into a distant country and being rid of the lad.

His mother spake then pleading, ‘O Sārihontō if you fare abroad, if you go as a bond slave into a distant country, if you perish among unknown men, who will have thought for thy mother or daily tend the hapless dame?’ And Sāri in evil mood answered singing out in light heart and whistling thereto:

Let her starve upon a haycock

Let her stifle in the cowbyre

And thereto his brother and sister joined their voices saying,

Who shall daily aid thy brother?

Who shall tend him in the future?

To which he got only this answer,

Let him perish in the forest

Or lie fainting in the meadow.

And his sister upbraided him saying he was hard of heart, and he made answer. ‘For thee treacherous sister though thou be a daughter of Keime I care not: but I shall grieve to part from Wanōna.’

Then he left them and Ūlto thinking of the lad’s size and growing strength relented and resolved to set him yet to other tasks, and is it told how he went to lay his largest drag-net and as he grasped his oar asked aloud, ‘Now shall I pull amain with all my vigour or with but common effort?’ And the steersman said: ‘Now row amain, for thou canst not pull this boat atwain.’

Then Sāri Kampa’s son rowed with all his might and sundered the wood rowlocks and shattered the ribs of juniper and the aspen planking of the boat he splintered. Quoth Ūlto when he saw, ‘Nay, thou understandst not rowing, go thresh the fish into the dragnet: maybe to more purpose wilt thou thresh the water with thresh- ing-pole than with foam.’ But Sāri as he was raising his pole asked aloud, ‘Shall I thresh amain with manly vigour or but leisurely with common effort threshing with the pole?’ And the net-man said, ‘Nay, thresh amain. Wouldst thou call it labour if thou threshed not with thy might but at thine ease only?’ So Sāri threshed with all his might and churned the water to soup and threshed the net to tow and battered the fish to slime. And Ūlto’s wrath knew no bounds and he said, ‘Utterly useless is the knave: what- soever work I give him he spoils from malice: I will sell him as a bond-slave in the Great Land. There the Smith Āsemo will have him that his strength may wield the hammer.’

And Sāri wept in wrath and in bitterness of heart for his sundering from Wanōna and the black dog Mauri. Then his brother said, ‘Not for thee shall I be weeping if I hear thou has perished afar off. I will find himself a brother better than thou and more comely too to see.’ For Sāri was not fair in his face but swart and illfavoured and his stature assorted not with his breadth. And Sāri said,

Not for thee shall I go weeping

If I hear that thou hast perished:

I will make me such a brother –

with great ease: on him a head of stone and a mouth of sallow, and his eyes shall be cranberries and his hair of withered stubble: and legs of willow twigs I’ll make him and his flesh of rotten trees I’ll fashion – and even so he will be more a brother and better than thou art.’

And his elder sister asked whether he was weeping for his folly and he said nay, for he was fain to leave her and she said that for her part she would not grieve at his send- ing nor even did she hear he had perished in the marshes and vanished from the people, for so she should find her- self a brother and one more skilful and more fair to boot. And Sāri said, ‘Nor for you shall I go weeping if I hear that thou hast perished. I can make me such a sister out of clay and reeds with a head of stone and eyes of cranberries and ears of water lily and a body of maple, and a better sister than thou art.’

Then his mother spake to him soothingly.

Oh my sweet one O my dearest

I the fair one who has borne thee

I the golden one who nursed thee

I shall weep for thy destruction

If I hear that thou hast perished

And hast vanished from the people.

Scarce thou knowest a mother’s feelings

Or a mother’s heart it seemeth

And if tears be still left in me

For my grieving for thy father

I shall weep for this our parting

I shall weep for thy destruction

And my tears shall fall in summer

And still hotly fall in winter

Till they melt [the] snows around me

And the ground is bared and thawing

And the earth again grows verdant

And my tears run through the greenness.

O my fair one O my nursling

Kullervoinen Kullervoinen

Sārihonto son of Kampa.

But Sāri’s heart was black with bitterness and he said, ‘Thou wilt weep not and if thou dost, then weep: weep till the house is flooded, weep until the paths are swimming and the byre a marsh, for I reck not and shall be far hence.’ And Sāri son of Kampa did Ūlto take abroad with him and through the land of Telea where dwelt Āsemo the smith, nor did Sāri see aught of Oanōra [Wanōna] at his parting and that hurt him: but Mauri followed him afar off and his baying in the nighttime brought some cheer to Sāri and he had still his knife Sikki.

And the smith, for he deemed Sāri a worthless knave and uncouth, gave Ūlto but two outworn kettles and five old rakes and six scythes in payment and with that Ūlto had to return content not.

And now did Sāri drink not only the bitter draught of thralldom but eat the poisoned bread of solitude and loneliness thereto: and he grew more ill favoured and crooked, broad and illknit and knotty and unrestrained and unsoftened, and fared often into the wild wastes with Mauri: and grew to know the fierce wolves and to converse even with Uru the bear: nor did such comrades improve his mind and the temper of his heart, but never did he forget in the deep of his mind his vow of long ago and wrath with Ūlto, but no tender feelings would he let his heart cherish for his folk afar save a[t] whiles for Wanōna.

Now Āsemo had to wife the daughter [of ] Koi Queen of the marshlands of the north, whence he carried magic and many other dark things to Puhōsa and even to Sutsi by the broad rivers and the reed-fenced pools. She was fair but to Āsemo alone sweet. Treacherous and hard and little love did she bestow on the uncouth thrall and little did Sāri bid for her love or kindness.

Now as yet Āsemo set not his new thrall to any labour for he had men enough, and for many months did Sāri wander in wildness till at the egging of his wife the smith bade Sāri become his wife’s servant and do all her bidding. And then was Koi’s daughter glad for she trusted to make use of his strength to lighten her labour about the house and to tease and punish him for his slights and roughness towards her aforetime.

But as may be expected, he proved an ill bondservant and great dislike for Sāri grew up in his [Āsemo’s] wife’s heart and no spite she could wreak against him did she ever forego. And it came to a day many and many a summer since Sāri was sold out of Dear Puhōsa and left the blue woods and Wanōna, that seeking to rid the house of his hulking presence the wife of Āsemo pondered deep and bethought her to set him as her herdsman and send him afar to tend her wide flocks in the open lands all about.

Then set she herself to baking: and in malice did she prepare the food for the neatherd to take with him. Grimly working to herself she made a loaf and a great cake. Now the cake she made of oats below with a little wheat above it, but between she inserted a mighty flint – saying the while, ‘Break thou the teeth of Sāri O flint: rend thou the tongue of Kampa’s son that speaketh always harshness and knows of no respect to those above him. For she thought how Sāri would stuff the whole into his mouth at a bite, for greedy he was in manner of eating, not unlike the wolves his comrades.

Then she spread the cake with butter and upon the crust laid bacon and calling Sāri bid him go tend the flocks that day nor return until the evening, and the cake she gave him as his allowance, bidding him eat not until the herd was driven into the wood. Then sent she Sāri forth, saying after him:

Let him herd among the bushes

And the milch kine in the meadow:

These with wide horns to the aspens

These with curved horns to the birches

That they thus may fatten on them

And their flesh be sweet and goodly.

Out upon the open meadows

Out among the forest borders

Wandering in the birchen woodland

And the lofty growing aspens.

Lowing now in silver copses

Roaming in the golden firwoods.

CIĄG DALSZY DOSTĘPNY W PEŁNEJ, PŁATNEJ WERSJI

![Ballady Beleriandu [Historia Śródziemia t. 3] - Tolkien J.R.R - ebook](https://files.legimi.com/images/d9a064a0adb1d268bcad560d0d7ed370/w200_u90.jpg)

![Kształtowanie Śródziemia [Historia Śródziemia t. 4] - Tolkien J.R.R - ebook](https://files.legimi.com/images/134e6e48cbe8bfb1e09963782cb6e7d7/w200_u90.jpg)

![Utracona droga i inne pisma [Historia Śródziemia t. 5] - Tolkien J.R.R - ebook](https://files.legimi.com/images/27b99912c0c92d4838c230b807018691/w200_u90.jpg)