39,99 zł

Dowiedz się więcej.

- Wydawca: London Wall Publishing

- Kategoria: Romanse i erotyka•Romanse

- Język: angielski

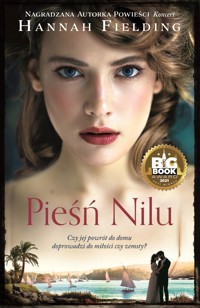

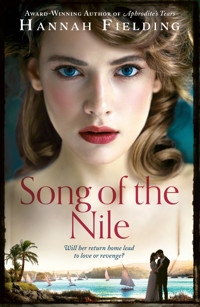

Luxor, 1946. When young nurse Aida El Masri returns from war-torn London to her family’s estate in Egypt she steels herself against the challenges ahead.

Eight years have passed since her father, Ayoub, was framed for a crime he did not commit, and died as a tragic result. Yet Aida has not forgotten, and now she wants revenge against the man she believes betrayed her father – his best friend, Kamel Pharaony.

Then Aida is reunited with Kamel’s son, the captivating surgeon Phares, who offers her marriage. In spite of herself, the secret passion Aida harboured for him as a young girl reignites. Still, how can she marry the son of the man who destroyed her father and brought shame on her family? Will coming home bring her love, or only danger and heartache?

Set in the exotic and bygone world of Upper Egypt, Song of the Nile follows Aida’s journey of rediscovery – of the homeland she loves, with its white-sailed feluccas on the Nile, old-world charms of Cairo and the ancient secrets of its burning desert sands – and of the man she has never forgotten.

A compelling story of passion and intrigue – a novel that lays open the beating heart of Egypt.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi lub dowolnej aplikacji obsługującej format:

Liczba stron: 1036

Podobne

Hannah Fielding was born and grew up in Alexandria, Egypt, the granddaughter of Esther Fanous, a revolutionary feminist and writer in Egypt during the early 1900s. Upon graduating with a BA in French literature from Alexandria University, she travelled extensively throughout Europe and lived in Switzerland, France and England. After marrying her English husband, she settled in Kent and subsequently had little time for writing while bringing up two children, looking after dogs and horses, and running her own business renovating rundown cottages. Hannah now divides her time between her homes in Ireland and the South of France. She has written seven previous novels, beginning with Burning Embers.

Hannah’s books have won various awards, including Best Romance for Aphrodite’s Tears at the International Book Awards, National Indie Excellence Awards, American Fiction Awards, NABE Pinnacle Book Achievement Awards and New York City Big Book Awards; and Best Romance for Indiscretion at the USA Best Book Awards. She also won the Gold Medal for Romance at the Independent Publisher Book Awards (for The Echoes of Love), plus the Gold and Silver Medals for Romance at the IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards (for Indiscretion and Masquerade).

Praise for Hannah Fielding’s first novel, Burning Embers:

‘An epic romance like Hollywood used to make …’

Peterborough Evening Telegraph

‘Burning Embers is a romantic delight and an absolute must-read for anyone looking to escape to a world of colour, beauty, passion and love. For those who can’t go to Kenya in reality, this has got to be the next best thing.’

Amazon.co.uk review

‘A good-old fashioned love story … A heroine who’s young, naive and has a lot to learn. A hero who’s alpha and hot, has a past and a string of women. A different time, world, and class. The kind of romance that involves picnics in abandoned valleys and hot-air balloon rides and swimming in isolated lakes. Heavenly.’

Amazon.co.uk review

‘The story hooked me from the start. I want to be Coral, living in a more innocent time in a beautiful, hot location, falling for a rich, attractive, broody man. Can’t wait for Hannah Fielding’s next book.’

Amazon.co.uk review

Praise for The Echoes of Love (winner of the Gold Medal for Romance at the 2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards):

‘One of the most romantic works of fiction ever written … an epic love story beautifully told.’

The Sun

‘Fans of romance will devour it in one sitting.’

TheLady

‘All the elements of a rollicking good piece of indulgent romantic fiction.’

BM Magazine

‘This book will make you wish you lived in Italy.’

Fabulous magazine

‘The book is the perfect read for anyone with a passion for love, life and travel.’

Love it! magazine

‘Romance and suspense, with a heavy dose of Italian culture.’

Press Association

‘A plot-twisting story of drama, love and tragedy.’

Italia! magazine

‘There are many beautifully crafted passages, in particular those relating to the scenery and architecture of Tuscany and Venice … It was easy to visualise oneself in these magical locations.’

Julian Froment blog

‘Fielding encapsulates the overwhelming experience of falling deeply, completely, utterly in love, beautifully.’

Books with Bunny

Praise for Indiscretion (winner of the Gold Medal for romance at the IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards and Best Romance at the USA Best Book Awards):

‘A captivating tale of love, jealousy and scandal.’

The Lady

‘Indiscretion grips from the first. Alexandra is a beguiling heroine, and Salvador a compelling, charismatic hero … the shimmering attraction between them is always as taut as a thread. A powerful and romantic story, one to savour and enjoy.’

Lindsay Townsend – historical romance author

‘Rich description, a beautiful setting, wonderful detail, passionate romance and that timeless, classic feel that provides sheer, indulgent escapism. Bliss!’

Amazon.co.uk review

‘I thought Ms. Fielding had outdone herself with her second novel but she’s done it again with this third one. The love story took my breath away … I could hardly swallow until I reached the end.’

Amazon.com review

Praise for Masquerade (winner of the Silver Medal for romance at the IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards):

‘Secrets and surprises … Set in Spain in the 1970s, you’ll be enveloped in this atmospheric story of love and deception.’

My Weekly

‘Hannah Fielding writes of love, sexual tension and longing with an amazing delicacy and lushness, almost luxury. Suffused with the legends and lore of the gypsies and the beliefs of Spain, there is so much in this novel. Horse fairs, sensual dreams, bull running, bull fighters, moonlight swims, the heat and flowers and colours and costumes of the country. A superb read.’

Amazon.co.uk review

‘This was honestly one of the most aesthetically pleasing and sensual books I’ve read in a long time.’

Amazon.co.uk review

‘Masquerade contains the kind of romance that makes your heart beat faster and your knees tremble. This was a mesmerising and drama-filled read that left me with a dreamy feeling.’

Amazon.co.uk review

‘This engrossing, gorgeous romantic tale was one of my favorite reads in recent memory. This book had intrigue, mystery, revenge, passion and tantalizing love scenes that held captive the reader and didn’t allow a moment’s rest through all of the twists and turns … wonderful from start to finish.’

Goodreads.com review

‘When I started reading Masquerade I was soon completely pulled into the romantic and poetic way Hannah Fielding writes her stories. I honestly couldn’t put Masquerade down. Her books are beautiful and just so romantic, you’ll never want them to end!’

Goodreads.com review

Praise for Legacy (final book in the Andalucían Nights trilogy):

‘Legacy is filled to the brim with family scandal, frustrated love and hidden secrets. Fast-paced and addictive, it will keep you hooked from start to finish.’

The Lady

‘Beautifully written, and oozing romance and intrigue, Legacy is the much-anticipated new novel from award-winning author Hannah Fielding that brings to life the allure of a summer in Cádiz.’

Take a Break

‘In the vein of Gone With The Wind, this particular book is just as epic and timeless. Written with lively detail, you are IN Spain. You are engulfed in the sights, sounds and smells of this beautiful country. Great characters … and a plot with just enough twists to keep it moving along … Start with book one and each one gets better and better. I applaud Ms Fielding’s storytelling skills.

Amazon.com review

‘Flawless writing and impeccable character building. Legacy takes the readers on a journey through the passions and desires that are aroused from romantic Spanish culture.’

Goodreads.com review

Praise for Aphrodite’s Tears (winner of Best Romance award at theInternational Book Awards, National Indie Excellence Awards, American Fiction Awards and New York City Big Book Awards):

‘For lovers of romance, lock the doors, curl up, and enjoy.’

Breakaway

‘With romantic settings, wonderful characters and thrilling plots, Hannah Fielding’s books are a joy to read.’

My Weekly

‘The storyline is mesmerising.’

Amazon.co.uk review

‘An intriguing mix of Greek mythology, archaeology, mystery and suspense, all served up in a superbly crafted, epic love story.’

Amazon.co.uk review

Praise for Concerto:

‘A captivating, enigmatic tale about the power of love … Concerto is a dramatic, mysterious, enticing love story that does a wonderful job of highlighting the magic of music and its ability to universally heal the mind, body, heart and soul.’

Goodreads.com review

‘Captivating sun-drenched escapism.’

Living France Magazine

‘An exceptionally beautiful and heart-touching read which will stay with you long after you finish … This book was a passionate, sweeping love story from start to finish, full of hedonism, romance, and gorgeous descriptions of some of the world’s most luxurious and beautiful places.’

Musings Of Another Writer

‘Totally recommended … With its gorgeous settings in the Riviera and Italy, this novel is a treat for all the senses, a kind of modern Beauty and the Beast, with secrets, villains and dangers in the palace where the beast Umberto has retreated. Meanwhile, music makes a beautiful redemptive healing thread throughout the novel, thoroughly apt and marvellous.’

Lindsay’s Romantics

‘One of the most beautiful romantic storylines that I have read in quite some time … I felt like I was at the opera from the comfort of my sofa while reading this beautiful story.’

Bookread2day

‘A beautiful, emotional tale which will leave a smile on your lips at the end.’

Book Vue

‘Words almost escape me with how beautiful this story was … A truly wonderful, romantic story that will sweep you away …’

Debra’s Book Café

Also by Hannah Fielding

Burning Embers

The Echoes of Love

Aphrodite’s Tears

Concerto

The Andalucían Nights Trilogy:

Indiscretion

Masquerade

Legacy

Song of the Nile

Hannah Fielding

First published in hardback and paperback in Poland in 2021 by London Wall Publishing sp. z o.o. (LWP)

First published in eBook edition in Poland in 2021 by London Wall Publishing sp. z o.o. (LWP)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a database or retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Copyright © Hannah Fielding 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to any real person, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permission with reference to copyright material. We apologise for any omissions in the respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future editions.

HB ISBN 978-83-956892-6-0

PB ISBN 978-83-956892-5-3

EB PDF ISBN 978-83-667980-2-1

EB ePub ISBN 978-83-667980-3-8

EB MOBI ISBN 978-83-667980-4-5

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Print and production managed by Printgroup, Poland

ePub/mobi made by Pracownia DTP Aneta Osipiak-Wypiór

London Wall Publishing sp. z o.o.

Hrubieszowska 2, 01-209 Warsaw, Poland

www.londonwallpublishing.com

www.hannahfielding.net

To my dear granddaughter, Philae, with my love and hope that you grow up to be a kind and wise woman, as was your great-grandmother Philae.

The dead cannot cry out for justice. It is a duty of the living to do so for them.

Lois McMaster Bujold

Prologue

Luxor, Egypt, 1938

Awave of anticipation ran through the crowded courtroom. A murmur rose among the assembly as the three judges, like ominous crows in their black coats and red sashes, filed back into the room. Mounting the platform, they took their places at the desk, looking down on the well of the court. Facing them, the lines of wooden benches that made up the gallery were filled with people, their glances flickering to the defendant’s cage at the side of the courtroom, while members of the press, for whom this trial had already provided significant headlines, leaned forward in their chairs. The self-important lawyers who had sat laughing, chattering and making cynical remarks turned their full attention to the magistrates and the room fell into the deepest silence.

The man standing inside the iron cage looked drawn, his face unshaven, his clothes hanging loosely on him. At the appearance of the judges he straightened and his dark eyes sought out the face of the teenage girl seated in the front row of the public benches, next to a grey-haired woman who gripped her hand tightly. The girl’s expression held so much anguish and fear as she stared back that the man in the dock looked pained; he gestured sadly with his shackled hands, as though trying to reach out and give her some comfort.

‘This court has found Ayoub El Masri guilty of the theft and illegal possession of Egyptian antiquities and therefore has sentenced him to five years in jail with hard labour.’ Another whispering current coursed through the well of the court, then deadly silence once more.

All eyes were on the man as he gripped the bars that held him prisoner. His face suddenly drained of colour and his breathing became short and laboured. Bringing his bound hands up to his chest, he staggered sideways, then crumpled to the floor of the cage. The young girl who had been watching the proceedings with such dread cried out and ran forward, desperately pushing her way past the officials to get to the cage, but her screams were drowned out by the chaos that ensued. Gasps and shouts went up; a handful of men swarmed around the iron door as it was unlocked and several officials rushed in to tend to the figure collapsed on the floor.

People were on their feet, jostling to see what was happening. Inside the cage, a young man was shouting to the officials to give him room, telling them he was a doctor. It seemed like an eternity to the girl as she fought her way to the front, where she clutched at the bars of the iron pen, her eyes wild with panic. The young man was kneeling, his strong hands clasped together on top of the older man’s chest, pushing down with rhythmical compressions. The girl shouted the doctor’s name, tears streaming down her face, but he kept going without lifting his head. Finally, he stopped and slumped back on his knees, and only then did he look up, straight into her eyes, his own grave gaze flooded with compassion. The next thing she knew, two maternal arms enfolded her, pulling her away, while sobs shuddered through her and the world slid into darkness.

Chapter 1

Luxor, March 1946

Aida El Masri was jolted out of her deep reverie and back to the present as the cream-and-grey 1936 Bentley came to a slow halt in front of a pair of gates.

‘We’ve arrived,’ announced the portly man sitting by the young woman’s side. ‘I’m very happy that you’ve decided to come home, Aida. The khadammeenservants have been waiting impatiently for you, too. There’s been a great atmosphere of joy and festivity at Karawan House since I announced your return.’

Aida smiled at Naguib Bishara. He’d been a very close friend of her father as well as his lawyer. Right to the end he had done his utmost for Ayoub El Masri and she would always be grateful for that. ‘It’s good to be back, Uncle Naguib.’

As the car’s engine idled, waiting for the gatekeeper to appear, Naguib’s charcoal eyes were warm as they settled on her. ‘I’m not sure that many of them will recognise you now. You’ve grown into a lovely young woman, but there’s hardly anything of you left.’

Aida laughed. ‘No more of Osta Ghaly’s excellent cooking, that’s the reason. Rationing helped too. We didn’t have all that butter and sugar you had here.’

Naguib hadn’t changed much, apart from his hairline which was rapidly receding towards an ever-growing patch of sparse grey hair at the back. Above a long and mobile mouth, he had of late grown a Charlie Chaplin moustache too – Aida had known him without one and she didn’t think it suited his smooth, rounded jawline. He had the sort of face you forget even while you’re looking at it, and maybe that was why he had decided to grow it. He still appeared to enjoy his food, however, judging from his waistline. Her mouth twitched with suppressed amusement. ‘Does Osta Ghaly still make his delicious konafa?’

Naguib chuckled loudly, patting a well-rounded stomach. ‘Unfortunately, yes!’ He raised his bushy black eyebrows conspiratorially. ‘And his basboussa is still the best in Luxor, though you must never tell him or it will go to his head.’

Aida’s smile became wistful as she gazed out of the open window at the tall palm trees edging the El Masri Estate, so integral to all the estates of Upper Egypt; she had always found the sound of their soft swishing at twilight so evocative and romantic. Breathing in the warm air, she sighed. It was the unmistakable scent of Egypt: the fusion of pungent earth and spices, of goats and chickens, and the distinctive tang of the cotton fields. She was finally home.

Eight long years had passed and the world had been ravaged by war since Aida had fled to England. She had never dreamed she’d be gone so long. Just for one year, she’d told herself, until the scandal had died down. She had been barely eighteen then, alone in the world except for a single relative, her English mother’s brother. George Chandler, a former MP living in the home counties before the war, had no children of his own and welcomed the daughter of his late sister with open arms. And so it was Aida began her self-imposed exile at his house in Berkshire.

Tragic though Aida’s circumstances were at that time, it seemed that fate, while callously closing one door for the young woman, had decided to open another. She always dreamed of becoming a nurse, ever since she had spent hours as a child hiding in the gardens of Karawan House when she was supposed to be in the kitchen helping her nanny, Dada Amina, with her prized date jam. There, she pored over history books about Florence Nightingale, ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ in the Crimean War, and Edith Cavell, the nursing heroine of the Great War. Finding herself in England, Aida had seen her opportunity to bring her dreams to fruition. With Uncle George’s help, she enrolled as a trainee nurse at the Royal London Hospital. Any romantic notions Aida might have harboured about her destined profession had been instantly dispelled by the long hours of work, attending lectures and studying for exams, not to mention scrubbing bedpans and making beds, all to the exacting standards of the fearsome matrons and sisters.

Then war had broken out in Europe and, even if she had wanted to, Aida could no longer return to Egypt. For the next six years her life took yet another direction. As the bombs dropped on the East End of London, her hands-on training became accelerated by necessity. She nursed soldiers maimed at Dunkirk and bound the wounds of burned pilots from the Battle of Britain, as well as looking after injured civilians caught in the Blitz. By now, Uncle George had come out of retirement and moved to Chelsea to help the war effort by working in the newly formed Ministry of Supply in the Strand. On those few occasions when she had time off, Aida would often stay at her uncle’s flat and George would take her to tea at The Ritz, a popular meeting place for politicians, aristocrats and minor royals. The glamour of those occasions was in sharp contrast to the ugly suffering she witnessed on a daily basis in her work.

If the death of her father had begun Aida’s passage to adulthood with a cruel jolt, the crucible of war completed it in a baptism of fire. The chubby and confused teenager who had left Egypt grief-stricken spent the war years growing into a resilient and focused young woman. Yet while she was able to help mend the broken bodies of so many casualties of war, she carried her own pain inside like an angry wound that would not heal. Now, after what seemed a lifetime away from her country, she was back in Egypt … here to clear her father’s name.

The creaking sound of metal broke into Aida’s reverie as Kherallah the ghaffir, rifle slung across his back, opened the gates. Dressed in a loose snowy galabeya, crowned with an enormous white turban, he raised his arm in salute as the car glided past, his face lit up with a smile that revealed dazzling white teeth. Aida waved at him. Good, loyal Kherallah. He had been gatekeeper for as long as she could remember. As a lad he had worked under his father, who had also been Ayoub El Masri’s gatekeeper and guardian of the estate before Kherallah took over.

Through the mango and guava trees, the bright glow of their fruit startling in that place of shadows and silence, loomed the pink house where she had been born: Karawan House, named after the nightingale. Aida loved the beautiful but sad legend about the bird, which Dada Amina used to tell her when she was a child. In Arab tales, the rose was believed to have originated from a sweat droplet fallen from the prophet Mohamed’s brow. Legend has it that from the time the first rose was created from this droplet all roses were white, until a nightingale fell in love with one of the blooms and pressed its body so hard on the petals that the thorns of its stem pierced the nightingale’s heart, turning the white rose to red with its blood, as well as creating the sad notes of the wounded bird’s song. Aida’s eyes travelled over the exterior of the building. Once so full of life and laughter, it seemed that Karawan House finally lived up to its name. After all these years, and with her father gone, it seemed shrouded in melancholy and drained of its former colour.

The finely carved old mansion that had been solidly built was now in bad repair. It displayed a neoclassical dark pink and cream crumbling stone façade with arches, pediments, columns and elegant, narrow windowsmasked by faded green wooden shutters. Its central structure was flanked by two lower wings, holding a ballroom and terrace on one side and a jardin d’hiver, the equivalent of an English conservatory, on the other, which was a suntrap even in winter. All the front rooms in the house looked out over the river and the desert, but the view from the back rooms was just as magnificent, taking in the grounds, with palm trees and green fields in the distance. It was not the most imposing house around, but it was grand enough, and despite losing her mother when she was only seven, Aida had enjoyed a happy childhood there with her father and Dada Amina. During term-time she had attended Cheltenham Ladies’ College, a boarding school in England, but whenever she could, she returned to her beloved home in Egypt for the holidays.

The car came to a halt at the foot of broad white marble steps, which swept up to the veranda that ran along the façade of Karawan House, and Saleh the driver rushed round to open the door for Aida. Ragab the gardener, who had tended the gardens since Aida was a tiny child, walked up the drive with great dignity to shake her hand, his deep, gentle eyes proclaiming him a man close to nature. ‘Hamdelellah Al Salama ya Sit,’he whispered, bowing a fraction with reverence.

‘Allah yé sallémak, ya Ragab,’ Aida said, returning his welcoming greeting. She hadn’t forgotten her Arabic, and it felt both strange and homely to be speaking the language again. The words came creakingly to the surface of her mind as if they had been deposited all these years somewhere in the pit of her stomach.

The mansion’s carved oak front doors were open and the numerous smiling staff of Karawan House stood at the entrance to welcome back their Sit Aida. There was Osta Ghaly, the kind, plump old cook who would secretly give Aida delicious sweetmeats when she was a child, conjured up in his kitchen where she was not allowed; Bekhit, the head suffragi, attired in his spotless white robe, red sash and red tarboosh – a man of great age who had been in the family’s service for fifty years; his eldest son, Guirguis, an alert young man with intelligent dark eyes that never seemed to miss anything, who would take over his father’s position one day, although remaining under Bekhit’s orders for now, while being trained for the job. There was Radwan the scullion, known as filfil, pepper, because he always interfered in other people’s arguments like pepper thrown into food; and his cousin Hassan the cleaner, a quiet youth who smiled a lot but didn’t say much. Both young men were the sons of fellahin, country folk, whose families had worked on the El Masri land for many generations. Then came Fatma, the washerwoman of the flashing gold teeth; Naima the maid, a young girl of seventeen who was only a child when Aida had left; and finally, Dada Amina, who had brought up her father Ayoub before caring for Aida.

Small and chubby, with curly black hair tied back under a triangular headscarf and wearing a flowery galabeya robe, Dada Amina had been a close confidante and second mother to the young Aida, the bond between them strengthening even further after Eleanor El Masri was diagnosed with cancer and died quickly afterwards. Though she was kind and possessed an exceedingly soft and sweet expression, Dada Amina was far from being a pushover and had kept the somewhat rebellious only child in check as she grew up. Once Aida had become a young woman, Dada Amina remained at Karawan House in the formidable role of housekeeper.

All these people had been in the service of Ayoub El Masri when he died, and Aida had insisted they should be kept on after his death even though she herself was making a hasty departure for England. Naguib, who had taken on the management of the El Masri Estate, had agreed, knowing that his friend Ayoub would have been proud of Aida’s loyalty to their household suffragis, many of whom had become almost part of the family. Today, the return of Sit Aida was regarded with obvious excitement. They beamed as, smiling, Aida shook hands with them one by one, thanking each of them for having looked after the family home during her long absence. When she reached the end of the line, Aida’s reunion with her old nanny was much more emotional. Dada Amina hugged the young woman to her heart and kissed her with tears glistening in her dark eyes.

‘Aida, habibti, my darling, all grown up!’ she exclaimed, holding Aida at arm’s length to inspect her. ‘Did you never eat during the war, ya binti, my child? You look so different, almost another person. But I would recognise you anywhere, ya danaya, my dear child … Allah, what have you done to your hair? You look like a film star! Baeti zay el amar, you have become as beautiful as the moon … Oh, it’s good to see you again!’ Fresh tears sprang from Dada Amina’s eyes as she clung to the girl whom she had missed as much as she would a daughter of her own.

Aida wiped her own damp cheeks and spluttered out a laugh. ‘And you haven’t changed at all, Dada Amina. Tell me, what keeps you so young?’

Naguib interjected, ‘Oh, bossing us all around and making sure we do what we’re told, isn’t that so?’, giving Dada Amina a cheerful wink and laughing heartily at his own joke.

Time may not have changed Dada Amina, but not so Aida. The housekeeper was right: she felt like a different person. It now seemed an eternity since that far-off afternoon, eight years before, when she had seen her father, Ayoub El Masri, standing behind bars like a caged animal in the dark courtroom, and had witnessed his demise minutes after the verdict was pronounced. Branded a thief, the shock had been too great for the renowned archaeologist and, within minutes, he had died of heart failure. It was a tragic finale to his life, and a brutal end to the insouciant days of Aida’s childhood. The memory of those first weeks of stark despair made her shiver.

Although she had no doubt about her father’s innocence, Aida had fled to England to get away from the hectoring of journalists and the malevolent tongues of society, who were quick to seize upon the scandal. The identity of the real culprit had been revealed to Aida the day her father was arrested, and she had carried the truth with her all through the war years. Now that she was back in Luxor, she would do her utmost to find the proof she needed to confront the coward who had let her father – his neighbour and long-time friend – go to jail. The same man who had ultimately caused Ayoub’s death.

* * *

Once the moment of demonstrative homecoming had passed, the staff dispersed, each going back to his job, except for Dada Amina, who accompanied Aida and Naguib Bishara into the house.

The hall of Karawan House was large and light. Its floor was made of cream calacatta marble, imported from Italy when the house was built in the early nineteenth century, its veins of gold giving it warmth and depth. The space was dominated by a grand wooden staircase, each side of which stood a pair of ionic columns in the same expensive warm stone. A magnificent Baccarat chandelier hung from the lavish ivory-coloured ceiling, whose decorative plasterwork panels were gilded and enriched by beige and brown low-relief details of various birds of Egypt.

Dada Amina led them across the polished tiled floor into the long, rectangular drawing room, made bright by four tall windows, their edges softened by faded damask curtains opening on to a terrace. From here the view was breathtaking: the slow-moving Nile lying like a pearlescent sheet, so still it seemed as though you could walk across the water to the farthest bank, where the pink hills of the Valley of the Tombs rose up, changing colour as the sun rode the sky. During the day, feluccas, the romantic gull-winged sailing boats used since antiquity, skimmed over the surface of the river like big white moths.

This room, like all others in the house, was done up in the formal English style – Ayoub and Eleanor had totally refurbished the house when they moved to Luxor, replacing the heavily gilded French furniture with the more sober and elegant Sheraton interiors.

Aida smiled at the familiar surroundings. A nostalgic pang of sorrow gripped her heart. Her father always said that her mother’s hand was to be seen everywhere in the elegance of the Karawan House interiors. She needed beauty all around her, as he had put it. The room was still as Aida remembered it. Painted a sunny yellow, its walls were adorned with oil paintings by David Roberts, Prisse d’Avesnes and Augustus Lamplough, which depicted the landscapes of Ancient Egypt, the River Nile, the desert, as well as scenes from Egyptian life. The golden oak floor was covered with fine antique carpets from Iran and Turkey and at each end of the beautifully proportioned room a fine Adam fireplace was surmounted by a gilded mirror. Both were lit in winter as the nights in this part of the world, contrary to the mild daytimes, were bitterly cold. Beautifully inlaid demi lune tables in satinwood stood on tapered legs between the windows, topped with antique Chinese ochre vases made into lamps, and in the middle of the room a large round table held a vase which Dada Amina always made sure to fill with sweet-smelling flowers from the garden, even when the house was empty. A set of deep-seat sofas and armchairs upholstered in pale celadon green damask faced each fireplace; Aida remembered nestling with her mother as a small child on one of those voluminous sofas while she read her stories, feeling the comforting rise and fall of Eleanor’s breathing against her cheek. Growing up, all she had to rely on were memories such as these, and the reminiscences of her father and Dada Amina.

Aida’s mother Eleanor and her family were passing through Egypt on their way back from India to England when she had met Ayoub El Masri at a drinks party at the British Embassy in Cairo. Ayoub was already a well-known and erudite archaeologist, renowned in his field, who had led many excavations and saved numerous Ancient Egyptian artefacts from destruction. Eleanor was young, beautiful and intelligent. It was love at first sight and the two had eloped and married very shortly afterwards. The ensuing scandal caused Ayoub, an only child who had lost his parents when he was still in his teens, to be disowned by the rest of his family and wide circle of friends, and Eleanor to be cut off from her own.

At first, they had been snubbed by the outraged Egyptian and British social circles – mixed marriages were not viewed with a benign eye in those days. Though he was originally from Cairo, Ayoub and his new wife moved to the quieter town of Luxor in Upper Egypt, where he could allocate more time to his excavation work while keeping an alert eye on the land he had inherited from his parents.

Society watched the golden couple furtively, and as Ayoub grew in status and his wife charmed her entourage, becoming an accomplished hostess, together they made valuable new friends in Luxor … and enemies too, because as the old Arabic saying goes: Envy is the companion of great success. And when that happens, as Dada Amina was always fond of telling the young Aida, ‘Who can pride himself on escaping the evil eye?’ It had not gone unnoticed by an older Aida that the El Masri family seemed destined to be blighted by suspicion and controversy.

Aida followed Naguib towards the large sofas and chairs by the fireplace while Dada Amina left the room, closing the door quietly.

‘Come, Aida, let’s sit down. I know you must be tired, but we need to talk,’ the lawyer said, as he took a seat in one of the high-backed armchairs.

‘You look quite worried, Uncle Naguib. Is anything the matter?’

‘You are right, I am worried. About you, Aida.’ Naguib took out his black-stemmed pipe and filled the bowl with tobacco.

‘About me? There’s no reason to be worried about me.’ Aida sank back into the sofa. ‘I’ve survived the war, haven’t I? Trust me, that wasn’t a piece of cake, so I can look after myself.’ She looked at him quizzically. ‘Is it money? I haven’t touched my inheritance, so unless something really untoward has happened I should be all right on that front.’

‘No, no. My dear Aida, you are a very rich girl. Ayoub left you a great fortune, which is still intact since you did not give me or anyone else a power of attorney before leaving.’ With a whoosh of a match, Naguib lit the brown bowl of his pipe. ‘My concern is that you’re a young woman on her own. It is a bad thing for a girl to be left fatherless, and no man to protect her,’ he said. The vibrancy and laughter that characterised Naguib’s personality had left his voice and he spoke sternly.

‘Yes,’ Aida replied faintly.

‘You have no brothers, no family.’

‘I know that I have no one here in Egypt, Uncle Naguib.’

‘You have the Pharaonys. Your families were always very close … and in some ways they are your only family now. Of course you also have me – something you can always count on – but I’m not getting any younger and life is unpredictable, as you have seen.’

The Pharaonys. For a moment, the familiar face of a young man swam into Aida’s mind – dark, disapproving eyes that turned her inside out. Eyes that had fixed on her the moment her father had died with compassion and regret. The image had haunted her painfully over the years, but now Aida’s face closed, her jaw set stubbornly. ‘The Pharaony family are of no interest to me.’

Naguib’s small shrewd eyes fixed on her as he puffed on his pipe.‘Don’t tell me that you still believe that Kamel Pharaony was behind that nasty business with your father.’

‘Yes, I do believe it. Nothing has changed as far as I’m concerned.’

‘But Kamel and Ayoub were best friends! What have you ever had to substantiate such an accusation, Aida?’

Aida took a breath. She had bottled up her resentment for so long that now she found it strangely difficult to speak. ‘Even though I have no proof, my information at the time came from a reliable source … The Nefertari statue belonged to Kamel Pharaony. He had brought it to our house earlier that afternoon.’

Naguib shook his head. ‘You know that Kamel denied that, so why do you persist in thinking such a thing?’

Aida paused. ‘Because my father was out, Kamel gave it to the maid, Souma Hassanein. He told her to put it in my father’s study and that he’d come back in the evening to discuss the authenticity of the piece with him. Those were her words.’

Naguib’s eyes widened. ‘She told you this? Kamel would never have entrusted a valuable piece to a servant. He is one of the most cautious men I know.’

‘Maybe, but Souma swore on her child’s head that that was what happened.’

The only problem was that the maid had disappeared before Aida could call on her to repeat her claims. Still, would it have helped anyway? A khadamma would never have been taken seriously.

Judging by Naguib’s expression, she had been right. ‘You can’t believe servants’ gossip.’

‘Gossip?’ Aida kept her tone even, not wanting him to think she was still the hysterical, grief-stricken teenager. ‘Someone like Souma wouldn’t have been able to make up something like that. Those were exactly the kind of words Kamel Pharaony would have used. Besides, why would she lie to me?’

Naguib shrugged. ‘Who knows? One can never be sure what ulterior motives these people have. Your father never liked Souma anyway. I know that a few days before the incident he caught her rummaging in some papers that were no business of hers, and he told her off. He only took pity on her because her husband had abandoned her and she needed a job to feed her son. He didn’t trust her, but Ayoub wasn’t a man to take the bread from a child’s mouth, so he kept her on. As our Arabic proverb says, Etak el shar le men ahssantou eleh, beware of him to whom you have been charitable.’

Aida frowned, digesting this new information. ‘Maybe, but I still don’t see what she had to gain by telling me such a story.’ Of course she had considered that Souma might have lied but she had gone over the maid’s words in her mind so often that nothing else made sense, except that she was telling the truth. But why would Souma be interested in her father’s papers? The old anger welled up inside Aida. She looked down, her fingers twisting the corner of a cushion. ‘Poor Father died far too young. He didn’t deserve what happened to him. Part of the reason I’ve come back is to clear his name.’

Naguib gave her an indulgent look. ‘How do you think you’ll be able to do that, ya binti, after so many years? I believe just as strongly as you do that Ayoub was innocent, but sadly, the real culprit is probably far away now.’

She raised her head. ‘Is he? Well, as the other saying goes, the corn passes from hand to hand, but comes at last to the mill. Whether it’s Kamel Pharaony or someone else, I will catch whoever was responsible for my father’s death.’

‘That won’t be as easy as you think, Aida. Have you forgotten so much of where you come from? People here will not approve of a woman digging around and asking questions. Anyhow, where would you start?’

‘With the only thread I have to follow. Souma, I’ll find her somehow.’

Yet Naguib’s words sank in heavily. Coming back to Luxor, Aida knew that she would have to navigate the conservative values of Egyptian society with some self-restraint. Egypt had remained in its own cocoon during the war and its society had failed to be touched by any form of sexual liberation, even in upper-class circles. It had been so different in wartime England. There, Aida had experienced the kind of social freedom in which her independent nature revelled. Suddenly she felt very isolated and alone in this place where she used to belong.

Naguib sighed. ‘Well, all I can say is that Souma is long gone now, and the harm she did cannot be undone.’

Aida glanced at him. It was ingrained in her to respect her elders but she deliberately refused to see his meaning. ‘I’m sure I don’t know what you mean, Uncle,’ she responded stubbornly.

‘You know that your father and Kamel Pharaony had spoken about an alliance between your two families. Kamel had asked for your hand on behalf his son Phares just before the tragedy. It is well known that you were almost engaged.’

‘Yes, that is so, but my father had never given his answer.’

‘Things have changed now. You are not that young anymore and their son Phares still wants to marry you …’

Why was he telling her this? He had no right to speak sternly to her. She had barely stepped back on Egyptian soil and was already being pushed into a marriage of convenience.

With a slight lifting of her head she said gently, ‘I have no intention of tying myself to someone I don’t love.’

‘In Egypt, habibti, the knowing and loving come after marriage.’

‘Not always. What about my parents? They married for love, did they not?’

‘Your parents were unusual, and look where it got them. Your father was disowned by his family for following his heart, not his head.’

‘Maybe,’ she agreed grudgingly. ‘But in the last eight years I’ve learned that life is too precious and short just to throw it away.’

Naguib gave a frustrated wave of his pipe. ‘But you would be doing the opposite of throwing away your life, you would be rebuilding it.’

‘Please, Uncle, let me finish … Marriage would be an important part – the most important part – of my life, and I must get it right. Though we grew up together, Phares is much older than I am. Even in those days I barely knew him.’

Naguib’s bushy brows shot up. ‘Oh, come now, Aida! You and Phares were hardly strangers. He often dropped by to visit your father and talk about his work. Phares took an interest in Ayoub’s findings, I seem to remember. Your father was very fond of the boy.’ He gestured with his pipe as an afterthought. ‘And you were often at Hathor or El Sharouk.’

To be pressed on her past feelings for Phares made Aida shift uncomfortably. ‘What I mean is, I didn’t know Phares as I would someone my own age. Besides, that was a long time ago, Uncle. You can’t expect me to commit to a man who is almost a stranger to me now.’ She gazed into his heavy-lidded eyes, which were watching her intently. ‘My father would never have forced me to marry someone I do not love.’

‘I am not forcing you, my dear. How could I? I have no power over you, I can only advise. You are a grown woman now. It is true that you look younger than twenty-six, but at your age most Egyptian women already have a string of children. I am speaking to you as if I were counselling my own daughter, merely trying to help you see things clearly. What you have been through hasn’t been easy. Phares understands that.’ Naguib leaned forward. ‘He was there that day. He knows how dreadful it was for you. The poor boy tried to save your father.’

Aida blanched, trying to keep the emotion from her voice. He had gone too far. ‘Are you saying that’s a reason for me to marry him?’

‘No, no, of course not, habibti.’ Naguib’s expression softened. ‘Look, all I’m saying is that Phares is a good match. When you were younger, the two of you always seemed to have something to say to each other, which is a good sign, no?’ He raised a thick eyebrow knowingly. ‘I recall that you seemed to like him when you were a teenager. Is that not so?’

Embarrassed to be discussing such things with Uncle Naguib, Aida gave a brittle laugh. ‘When I was younger I had a schoolgirl crush on Phares, no more. We were worlds apart in our thinking, and there was no question of love between us.’ Hearing the words leave her mouth, that odd feeling of unease returned.

‘There are other factors to consider,’ Naguib pressed on, regarding her through a tendril of pipe smoke. ‘Your father’s esba, estate, is in a pitiful state, because without a power of attorney, no one could do anything about it. If you wanted to sell it today, I doubt you would get a reasonable price for it. Having Kamel oversee that side of things has been very useful, Aida. Plus, the Pharaonys’ land borders yours, so it would be normal for your two families to unite.’ The voice was deep, grating, and after eight years of absence, Aida found it foreign, instantly conjuring up the ruthless facet of a different world with customs her father himself had disobeyed by marrying a foreigner, and had paid the price.

Aida gave Naguib a mutinous look. ‘That is no reason to give up my freedom. I’m still not sure what my plans are. I may want to go back to live in England.’

‘You have always been headstrong, with a streak of recklessness that worried your father.’

‘No, I’ve always known what I wanted. I didn’t want to leave Egypt, and even when I was at school, I always preferred coming home to be close to my father. Now he is gone, things are different. There are greener pastures out there.’

The lawyer shook his head disapprovingly. ‘Adventurousness is not a good trait in a woman. One day you’ll get yourself into trouble, and God help you if people who care about you are not around to help.’

At this moment, Dada Amina came in bearing a tray of tea and a plate ofkonafa and basboussa, dainty little pastries made with nuts and syrup.

‘Osta Ghaly made them especially because he knows how much Sit Aida is fond of them,’ she chuckled. She glanced at Aida as she set down the plate on the table. ‘And now that you are back, we must feed you properly again.’

Aida burst out laughing, a crystalline laugh that used to echo through the house before she had left. Osta Ghaly added coconut and orange flower water to his basboussa to give the cake his personal touch and she had always found it delicious. ‘I will go to the kitchen later, like I used to when I was a child, and thank him personally.’

Dada Amina beamed. ‘That will be very kind of you, ya Sit, ya amira. Thank you.’

After she had left the room, Naguib looked at Aida, sitting in front of him, and she read the disapproval still shadowing his features.

‘You say you are thinking of going back to England? That is a bad idea, habibti. Your place is in Egypt. Don’t forget that you are Egyptian.’

‘Yes, but I am also English.’

The lawyer shook his head. ‘You are someone here. Your father was a loved man, Allah yerhamoh, may God rest his soul.’

Aida sent him an arched look. ‘You seem to forget how much he was criticised after the trial.’

‘Society is fickle. That was a long time ago and memories fade. You carry the El Masri name, which is a respected one in Egypt. In England, as far as I know, you are no one.’

Her face flushed with irritation. ‘That’s not so. My uncle was a respectable MP who worked hard during the war to make sure people didn’t starve, and I have made many friends there. I went to school in England, remember?’ Aida knew that she was being deliberately stubborn, but in this country where men thought they had the right to rule women as they pleased, she felt slightly vulnerable and needed to mark out her position immediately.

Naguib remained undeterred. ‘England is going through bad times. The war has ravaged Europe and people are emigrating to Australia, New Zealand and America, where there are economic opportunities. You already have assets here – ones that need looking after. The house and the land are in a sorry state. To bring Karawan House back to its former glory and for the land to deliver the crops it did before the war, you will need to spend a great deal of money, which you have, of course. As I’ve said, you are far from being a pauper, but it is much too heavy a burden for a woman alone to bear, and that is where you would benefit from marrying Phares Pharaony.’

‘I’m quite able to stand on my own two feet and besides, how do you know that Phares still wants to marry me? He used to disapprove of me, thought I was too liberal and impulsive, although he probably considered that I was young enough to be tamed by a husband one day.’

‘As you know, although I am not Kamel Pharaony’s lawyer, he is a good friend of mine. When a few weeks back I told him you were coming home, he asked me to test the waters, find out if you would still consider marrying his son. It would be an alliance between two great families and would multiply both your riches. Not only that, but Phares is an eminent general surgeon now, fast becoming a legend in the medical world. He is well-respected.’

Phares, a surgeon … Aida was not surprised that he had become successful. He had always been driven by his love of medicine and his dreams of becoming a surgeon. She thought wryly of how protective he had always been towards others – an innate caring quality – though when they were younger, Aida had been infuriated by it whenever it had been directed towards her.

Naguib emptied his pipe into an ashtray. ‘Anyhow, the Pharaonys have been very decent. They kept a vigilant eye on your land and they even hired a few ghoufara to look after it, especially at night. The trafficking in antiquities and hashish since the war has increased tremendously and the smugglers and mattareed, outlaws, tend to hide in the grounds of empty, unguarded estates. Sometimes they even try to appropriate the land, squatting on it, and the police have great difficulty in getting them out. I wouldn’t dismiss an alliance with the Pharaonys so cavalierly, habibti … Think about it.’

‘Uncle, it was in their interests to guard my land since it adjoins theirs. No one does anything for nothing in this day and age.’

‘You are much too young to have such cynical thoughts, my dear child. The Pharaonys are good people, and they are well intentioned. I take it you will at least see Camelia while you are here?’

Camelia Pharaony was Phares’s younger sister and she and Aida had been close friends since they were little girls. For that reason, even though Aida had wanted nothing to do with the Pharaony family after she’d left for England, she found it hard to bear a grudge against Camelia herself. Still, they hadn’t corresponded during the war and Aida wondered if they would even get along anymore.

‘Yes, of course,’ she answered hesitantly. ‘We have a lot to catch up on.’

‘Perhaps she will make you see sense.’

Aida reached for a knife to cut a small piece of konafa. ‘Please, Uncle Naguib, don’t insist. The matter is closed. Let’s enjoy Osta Ghaly’s wonderful pastries and talk about something else.’ She pushed a plate across the table in his direction.

Naguib hesitated, then smiled in resignation. ‘As you wish, my dear.’ He took a piece of basboussa and demolished it in a couple of bites. ‘I’ll let you relax for a few days before taking you around the property with Megally. You remember him, the estate manager? He would have come to meet you today, but I’m afraid his wife is very ill in hospital.’

‘Yes, yes, of course I remember Megally. Poor man. Is he still working? He must be quite old by now.’

‘Yes, and he’s very good with the fellahin, the workers. They have great respect for him.’

‘I do hope his wife will be all right. In the meantime, I’ll reacquaint myself with the estate. Also, please could I take a look at the accounts? Perhaps next week?’

Naguib wiped the crumbs from his mouth and pushed himself slowly out of his chair. ‘Yes, of course. The books are already in your father’s office. And now I must go. Your aunt Nabila is cooking tonight and that’s something worth getting home early for.’ He chuckled to himself. ‘I’ll call by again soon.’

Aida accompanied Naguib to the front door, said her goodbyes and made her way back down to the kitchen to thank Osta Ghaly for his delicious pastries.

* * *

Up in her bedroom, Aida looked around her. It was a beautiful, gracious room, spacious and light, hung with English chintzes and furnished in English fashion. For Aida’s sixteenth birthday, Ayoub had totally refurbished his daughter’s bedroom. ‘You’re no longer a child and should have the bedroom of a young lady now. Your mother would have enjoyed doing it up for you and I hope I have done her proud,’ he had told her when, after a week spent in Cairo with Camelia Pharaony, Aida had come back to Luxor for her birthday and discovered the surprise.

The nursery had been turned into the most luxurious room Aida could have dreamt of, painted in different shades of soft green, its silk curtains patterned with colourful fruit. She looked around her to find it unchanged. The wide single bed, covered in a silk peach bedspread and draped with a mosquito net, faced the two French windows that opened on to a narrow veranda, and in one corner of the room two comfortable armchairs sat either side of a small round table.

Next to one window stood a delicate painted escritoire and chair; in front of the other, an elegant mahogany dressing table and mirror with its old Roman curule seat covered in velvet. In between the two, an Italian ebonised mahogany table held a number of photographs of Aida at different stages of her life as well as photographs of Eleanor and Ayoub. A tall, painted parcel-gilt glass cabinet bookcase took up much of the left wall, and on the opposite side was a large mahogany wardrobe and cheval mirror.

Aida sighed as she looked at the pretty chintzes, the David Roberts’ prints of Egyptian monuments that adorned the walls, the miniature dolls’ tea set and bibelots of frail china in the glass cabinet, which her parents had brought back from England one Christmas, the gleaming silver ornaments representing various Egyptian artisans and sellers. Each item had a memory connected to it. She went to the table which held her history in photographs and picked up the last picture she’d had taken with her father only a few days before the tragedy. She seemed so young – a child – so different to the way she looked today. As Dada Amina had said: almost a different person.

The mirror returned the reflection of a young woman with burnt gold hair, styled in Rita Hayworth fashion. When she left Egypt, it had been in a short bob, to the nape of her neck, but in spite of its having been fashionable during the war, she had let it grow, and had treated herself to a proper hairstyle before leaving England. Brushed back simply from her face, with a flat crown and parted on the side, it now undulated in a rich and shining cascade past her shoulders.

Unusually large almond-shaped sapphire eyes fringed by thick, dark, almost-too-long lashes gave her face a mysterious and languorous expression. With just a suggestion of shadow underneath them tonight, they gazed back at her critically. She was rather pale. Her cheeks had lost their youthful glow – the lack of sun, the endless grey and drizzle of the English weather, hadn’t suited her. She had also grown taller, much taller, and had lost the extra pounds that her father had indulgently called puppy fat. The roundness of her face had given her a look of plainness when she was a girl, but now the sharpness of her elegant cheekbones contrasted strikingly with her full lips. Yes, it really was a different woman that stood in front of the cheval glass. But Uncle Naguib was right: she still didn’t look her age, a fact which irritated her because when people first met her they tended not to take her seriously.

Aida stepped on to the veranda. She felt singularly lonely as she looked out on to the velvety night, reminiscing. It was hard to think of a future back in Egypt without her father. Beyond the house where the clear sky came down to the sand, the afterglow of pink faded to yellow and mother-of-pearl, giving way to a blue sky of twinkling stars. It reminded Aida that she had changed continents and climate in less than twenty-four hours, and that in this part of the world darkness came quickly.

The days here were short, and twilight, the loneliest of hours, was unknown. The sun went down dramatically – bang – just like that, below the rim of the desert. For the last fifteen minutes, feluccas were drawing in beside the banks of the Nile, with a creaking of windlass and the whine of great sails, their chains rattling as they moored. A scene her eyes had settled upon many times before, but had never really registered the beauty and serenity of it. How unlike the world she had left behind was this remote universe of sand, water, palm trees and statues; how different from the images of war she had witnessed, how wonderfully peaceful and removed from reality! Now, as she closed her eyes and breathed in the warm night, she could hardly believe that she was back.

Aida loved this land where she had grown up. Everything was familiar; she fitted in here and would have never left if her father hadn’t died in such tragic and shocking circumstances. She would have probably married Phares. She had carried a torch for him since her early teens, spellbound by his charisma, even though the six years that separated them meant that she hadn’t had much to do with him. Just enough to know that she regarded him with as much frustration as admiration. It had been the same for as long as she could remember.

When she was much younger, Aida had found the teenage Phares a source of annoyance: the overbearing older brother who always knew better. His sister Camelia, who was a year older than Aida, would often invite her over to Hathor, the Pharaonys’ family home, in the school holidays. Phares would sometimes make an appearance when he was still living at home, studying for his college exams. One afternoon, when Aida was nine or ten, he had caught her hurtling down a garden slope far too quickly on her bicycle. When he had called out to her to stop, she had lost control of the handlebars and ended up in a hedge with a badly grazed shin. Phares had quickly helped her into the kitchen, all the while admonishing Aida for her reckless behaviour.

‘If you hadn’t shouted at me, I would have been fine,’ she had protested vehemently.

But Phares would have none of it. ‘Girls aren’t meant for wheels, they should stay on their feet,’ he had told her with a stern look. And while silently outraged by his response, she appreciated how much care he took in cleaning the blood off her leg so that it didn’t hurt too much.

Another time, Aida had found an injured bird in the gardens of Karawan House. She and Camelia had been working out what to do with it when Phares arrived to fetch his sister home for supper. Immediately taking charge, he had instructed Aida to find a well-ventilated box and a small towel. Returning with it, she was told by Phares that he would take the bird back to Hathor. Aida had objected immediately. ‘But it’s my bird, I found it!’ she cried. ‘I can look after it here.’