Intuition and Analysis. Roman Ingarden and the School of Kazimierz Twardowski ebook

Anna Brożek, Jacek Jadacki

129,90 zł

Dowiedz się więcej.

- Wydawca: Copernicus Center Press

- Kategoria: Religia i duchowość•Filozofia

- Język: polski

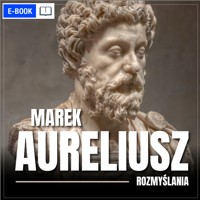

The photograph on the front of this book is, in a way, a double symbol. Firstly, it presents the Lvovian philosophical milieu around 1925 when its three main figures were Kazimierz Twardowski, Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz, and Roman Ingarden. Secondly, it reflects the tension between the two approaches to philosophy referred to in the title: “Intuition and Analysis.”

The central item of the photograph is the couch on which the three gentlemen are sitting. If we did not respect linguistic purism too much, we could say that they are connected by a common sofa, with the word “sofa” sounding similar to “σοφία:” wisdom, reason, ratio, that is, in technical terms, anti-irrationalism. However, the ideal of wisdom may be realized differently and this is where tensions appear despite general agreement.

Each of the three men is sitting differently: Twardowski and Ingarden have their legs crossed at the ankles; body language experts would perhaps say that they are restraining their “boiling” negative emotions. However, in Twardowski, this is paired with self-confidence (legs spread), and in Ingarden – uncertainty (legs joined). Indeed, Ingarden preferred “deep” phenomenology to Twardowski’s “small” analysis but could not feel safe near the Lvovian master of clarity.

Ajdukiewicz, relaxed with his legs and arms crossed, distances himself from them both: he is sitting close to his colleague Ingarden but turned sideways, away from him. He looks with respect at his teacher and father-in-law Twardowski, but sits at a “safe” distance from him. Indeed, Ajdukiewicz’s “sharp-logical” attitude towards philosophical problems differed both from Ingarden’s approach and the “soft -logical” program of Twardowski.

The three philosophers are surrounded by their students; some of them (for instance, Izydora Dąmbska, Leopold Blaustein) are also central figures in this book.

The interpersonal and intertextual relations between Ingarden and the Lvov-Warsaw School examined in this book are not only of a historical character. Even now, they may serve all truth-lovers in finding their own way of dealing with philosophical problems.

Contributors:

Anna Brożek, Aleksandra Horecka, Jacek Jadacki, Ryszard Kleszcz, Dariusz Łukasiewicz, Janusz Maciaszek, Adam Olech, Witold Płotka, Paweł Rojek, Wojciech Rechlewicz, Jacek Wojtysiak, Jan Woleński.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi lub dowolnej aplikacji obsługującej format:

Liczba stron: 581

Podobne

Preface

In 2020, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the death of Roman Ingarden (1893-1970), one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century and a leading representative of phenomenology. Ingarden was strongly associated with the Lvov-Warsaw School (hereinafter, briefly: LWS), a school founded by Kazimierz Twardowski in Lvov in 1895. Although Ingarden is not considered a member of the School, there are some interesting connections between him and Kazimierz Twardowski, as well as other members of the LWS. Firstly, before Ingarden began his studies under the supervision of Edmund Husserl in Göttingen, he had studied for a year in Lvov under Twardowski. Secondly, in 1933 he got the Chair of Philosophy in Lvov, where Twardowski’s students were active at the time. Thirdly, after World War II, Ingarden became close to some of Twardowski’s students and colleagues; at the Jagiellonian University he cooperated with Izydora Dąmbska, one of Twardowski’s former student and his last assistent. Ingarden also shared a scientific ethos with the LWS, which was probably motivated by common tradition and intellectual origin: both Twardowski and Husserl were students of Franz Brentano.

All these facts form an interesting historical background of the interactions and tensions between Ingarden and the members of the LWS, and, more broadly, between early analytic philosophy and the phenomenology movement. These relations and tensions are explored in this book.

In the “Introduction,” the editors of the volume sketch out the general picture of the relations between Ingarden and the members of the LWS. First, the close personal ties between Ingarden and Twardowski as well as his pupils are presented. Second, the research program of the LWS is compared with the program formulated by Ingarden. Both programs involve the use of some specific research methods. It is demonstrated that despite the undoubted differences between the research methods declared and actually applied by Ingarden and by representatives of Twardowski’s School, both kinds of methods may be counted as analytical.

Chapter 1 (by Jan Woleński) may be considered an exposition and justification of the counter-thesis: that Ingarden’s philosophy was radically opposed to that represented by Twardowski and his students. Thus, there was no possibility of a compromise between both styles of doing philosophy. Both sides, Ingarden as well as members of the LWS, stressed this situation. Yet there are many shorter or longer passages in Ingarden which can be understood as direct or indirect criticism of the LWS, particularly of logic and its role in philosophy. Similarly, some fragments of the writings of the LWS might be interpreted as critical allusions to Ingarden, for instance, concerning a priori or intuition as the devices applied in the cognition of the essences.

Contrary to chapter 1, chapter 2 (by Jacek Wojtysiak) can be considered a “relief” for the view expressed in the “Introduction,” however with the proviso that Ingarden developed non-standard methods of analysis. As examples of these methods, the author gives: the analysis of the historical philosophical concepts (e.g., the analysis of the concept of form), which enables Ingarden to clarify and order philosophical terminology; ontological analysis (e.g., the analysis of existence), by means of which Ingarden discerns, in the analyzed entities, the aspects, factors, moments, etc. that can be grasped only by means of ‘higher order abstraction’; metaphilosophical combinatorial analysis (e.g., the analysis of the possible solutions to the realism-idealism controversy) using which, and drawing on other types of analysis, Ingarden establishes lists of non-contradictory possibilities that correspond to all philosophical positions concerning a given question.

In the “Introduction” and chapters 1 and 2, there are numerous references to Ingarden’s metaphilosophical views. Chapter 3 (by Ryszard Kleszcz) also refers to Ingarden’s metaphilosophy, beginning with the observation that in his works, we find essential statements regarding the nature of philosophy, its relation to science, or the specificity of its methods. These metaphilosophical remarks were formulated in the systematic works as well as in texts of a fragmentary nature. The author of the chapter provides a comprehensive reconstruction of Ingarden’s metaphilosophy, projecting it on the one hand against the background of Brentano’s thoughts, and on the other – comparing it with Kotarbiński’s views as well as with the main metaphilosophical assumptions of a logical positivist from the Vienna Circle.

Part II of the volume focuses on a comparative analysis of Ingarden and individual representatives of the LWS, emphasizing differences rather than similarities. We used the terms “confrontation” and “convergence” in the title of this part because, in our opinion, these terms are perfect for describing the historical process that took place in the development of relations between Ingarden and the representatives of the LWS. The starting point was a confrontation, but it was a confrontation between two fractions within one current, namely within that of so-called scientific philosophy. Both fractions strongly emphasized differences between them, especially in the research METHODS used. Over time, however, there has been an ever greater convergence: the gradual alignment of research RESULTS. In our opinion, such a convergence was fostered, among other things, by the fact that the differences in the (methodological) starting points were not as great a the adversaries had thought.

Chapters 4 (by Adam Olech) and 5 (Janusz Maciaszek) concern the opposition: Ingarden versus Ajdukiewicz.

In chapter 4, the polemic of Ingarden with Ajdukiewicz is analysed, the subject of which was the meta-epistemological project of the semantic theory of cognition by Ajdukiewicz, on the basis of which he conducted a critique of Rickert’s transcendental idealism. The core of this polemic was the dispute over the role of language in cognition and knowledge (understood as the product of the cognitive processes), as well as the dispute over the way of understanding the term “cognition.” Two different meta-epistemological concepts clashed in this polemic – the analytical and the phenomenological concept, i.e., the analytical concept understood narrowly and understood broadly. Despite exposing the differences between Ingarden and Ajdukiewicz (as a “pure” analyst), the author is inclined to conclude that phenomenology is also an analytical philosophy, with a broad understanding of analyticity.

The author of chapter 5 is not limited – as the title would suggest – to the juxtaposition of Ingarden’s and Ajdukiewicz’s conceptions of meaning and to indicating their common inspirations. In this chapter, it is about how these conceptions deal with the problems of contemporary philosophy of language, such as the semantics of empty names, the controversy between millianism and descriptivism over the nature of proper names, the problem of substitutability in intensional contexts, meaning holism, compositionality, and the boundary between semantics and pragmatics. In light of these analyses, the assessment of Ingarden’s conceptions (which are the main focus of this chapter) is ambiguous.

Chapters 6 (by Dariusz Łukasiewicz) and 7 (by Wojciech Rechlewicz) are related to each other in so far as, although Ingarden’s “partner” in the first chapter is Czeżowski, and in the second chapter – Twardowski, it is commonly known that Czeżowski was one of the most congenial students and followers of Twardowski.

It is rather obvious that neither Ingarden’s nor Czeżowski’s doctrines imply any theistic metaphysics containing the thesis on the existence of the personal Absolute. The aim of chapter 6 is to investigate whether these doctrines are in any case compatible with such a classical theism. Such a situation is generally permissible on the basis of the belief shared by Twardowski and his students that (simplifying) philosophical theses and worldview theses are logically independent from each other. The answer to the main question of the chapter requires the reconstruction of two philosophical parts of the doctrines of both philosophers: their conceptions of values and their views on so-called metaphysical cognition. After making such a reconstruction, the author of the chapter comes to the conclusion that the positive answer is more justified than the negative one. This indirectly justifies the opinion that also that Ingarden’s and Czeżowski’s general views on the philosophy-worldview relationship are also basically similar.

In chapter 7, a certain thread is expanded, already mentioned in the “Introduction,” namely concerning Ingarden’s reaction to one of Twardowski’s program articles: “On Clear and Unclear Philosophical Style.” Ingarden accepted the postulate to write philosophical works clearly which was issued by Twardowski in this text. He also agreed with Twardowski’s statement that unclearness of thoughts results in the work being unclear. However, Ingarden emphasized that considering a given work unclear may result from the reader’s lack of the appropriate competences. He also rejected Twardowski’s recommendation to give up guessing the thoughts of any author that writes unclearly. Let us add that both of Ingarden’s arguments in this discussion had some personal subtexts.

The last two chapters of part II – chapters 8 (by Aleksandra Horecka) and 9 (by Witold Płotka) – are connected not only by the fact that Ingarden is juxtaposed with Blaustein in them. The point is that in these chapters their authors emphasize not the opposition between Ingarden and Blaustein, but mutual influence of these philosophers.

Pursuing the intention to identify these mutual influences on the Ingarden-Blaustein line in terms of aesthetics, and more specifically in their theories of image, the author of chapter 8 begins with a detailed presentation of these theories and the course of how these philosophers exchanged thoughts about their concepts. It turns out that although both philosophers often had similar sources of inspiration, and although, for example, Blaustein often quoted Ingarden’s writings, it is difficult to conclude that he was a continuator of Ingarden’s thought.

The author of chapter 9, influences and reinterpretations of Ingarden’s philosophy – especially in the theory of consciousness – in Blaustein, comes to similar conclusions. The fact that he was a student of both Twardowski and Ingarden gives some researchers of Blaustein a reason to classify Blaustein as an “analytic phenomenologist,” who combined the tradition of the LWS with phenomenology. The chapter shows the limitations of this classification. It is argued that Blaustein represented rather a psychological trend of the School, and for this reason his use of “strict” analysis was limited.

While part I of the volume has a clear historical character, and part II can be described mainly as “comparative,” part III is primarily critical. In this part, certain detailed Ingardenian theoretical proposals have been considered according to the standards adopted in analytical philosophy, and in particular in the LWS, or (as in chapter 10) to illuminate the underlying presuppositions in Ingarden’s position by drawing on several later examinations of the relevant topics. The critical analysis, carried out in chapters 10 (by Paweł Rojek), 11 (by Jacek Jadacki), and 12 (by Anna Brożek), assumes that these analytical standards may be applied to Ingarden’s views, regardless of whether he is aptly considered an analytical philosopher or not.

In chapter 10, the object of criticism is Ingarden’s “realistic trope theory,” concerning the ontic status of particular properties and universal ideas. The fundamental objection against such a theory is that according to it, universals are transcendent forms, and such forms, arguably, cannot be true universals. The author argues that Ingarden’s theory of universals is, in fact, a kind of “hidden nominalism.” Then he tries to show that although Ingarden’s ontology cannot be reinterpreted in a true realistic way, some of its elements might be used to formulate a more appropriate theory.

The criticism provided in chapter 11 is much more radical; in this chapter, four types of ontic subordinations are analyzed, namely: heteronomy, derivativeness, non-self-reliance and dependency; they constitute the key cell of Ingardenian ontology. The analysis leads to the conclusion that the concepts constructed by Ingarden are either logically incorrect, or are not sufficiently explained, or refer not to ontic but to semantic relations. The criticism contained in this chapter is “negatively” destructive, i.e., the author does not propose a “positive” correction of Ingarden’s solutions.

It is different in chapter 12, in which Ingarden’s conception of an ontic category and the essence of music composition is criticized internally (from the point of view of Ingarden’s own assumptions) and externally (when the very assumptions are revised). Ingarden bases his investigations on the elitist analytic corpus (he considers only outstanding works of Western Music) and employs liberal ontological assumptions (he allows many different categories of objects). With these assumptions in place, Ingarden reaches his solution, namely that the work of music is a schematic, purely intentional object. This seems optimal. The perspective changes if we go beyond the elitist corpus or accept more restrictive ontological assumptions.

We believe that three parts of this book do justice (to use one of Ingarden’s favourite words) to his “analytical” successes and failures.

Perhaps many readers would point out that in the “Ingarden trial” only “analytical” prosecutors participate, and there are no “phenomenological” defenders; it is difficult in such a “trial” to obtain an objective judge’s verdict. We have two excuses. The first is of a “personal” nature: it is not easy to find defenders of phenomenology willing to appear in a trial in which analysts “accuse;” this lack is partially weakened by the fact two of our authors are genetically connected with Ingarden as students of his students: Jacek Wojtysiak (PhD supervised by one of Ingarden’s successors: Antoni B. Stępień) and Paweł Rojek (his "Ingardenian" line of PhD supervisors includes Jacek Szymura and Michał Hempoliński; he also worked under two "half-Ingardenians": Władysław Stróżewski and Jerzy Perzanowski). The second excuse is of a “technical” nature: while analytical tools are rich enough to analyze phenomenological methods and results, phenomenological tools do not have such technical “power;” it is symptomatic that Ingarden himself, when he entered into polemics with his analytic partners, transformed himself nolens volens into an analyst.

The work is largely historical in nature. Therefore, in the bibliographies for individual chapters, we give as indicators the dates of the first original editions of individual texts (with the exception of ancient ones), as it is important for tracing the filiation of ideas between authors. If we use quotations from existing English translations, we identify them in the bibliographic description by the publication dates of these translation.

Anna Brożek & Jacek Jadacki.

Warsaw, 14.06.2021.