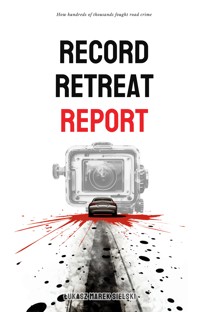

RecordRetreatReport

How hundreds of thousands fought road crime

Łukasz Marek Sielski

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by SIELAY Ltd.

Copyright © 2024 Łukasz Marek Sielski

Revision 1 – July 1sth 2024

The right of Łukasz Marek Sielski to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor may it be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Proofreading and inline-editing Martin Ouvry.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

www.sielay.com

www.phonekills.com

Amazon Kindle ASIN B0D6DP9KHX

EBOOK Draft2Digital ISBN 979 8 227 35303 0

Amazon Paperback ISBN 979 8 853 97773 0

Amazon Hardcover ISBN 979 8 325 43796 0

Please subscribe to the author newsletter on https://phonekills.com

Some think using the phone while driving, speeding, or parking on zigzags is a victimless crime. They are frustrated that a driver caught doing these things can lose their driving licence and sometimes, as a result, their job. But the law wouldn't be in place if there weren't some tragedies resulting from such behaviour. And some motorists ignore that fact and takes the risk. Still more are likely to blame someone who has reported their behaviour. Blaming a witness is like blaming the tree that was in the way of a drunk driver who lost control of their vehicle.

To all victims of road crime

"The death of one man is a tragedy; the death of millions is a statistic"[i]. A pedestrian killed by a cyclist is a breaking story. One thousand seven hundred people killed by motorists is just a number.

Contents

Let’s clean the path

A land of snitches

Pioneers

In the beginning, there was a camera

The platform

Magnatom

Not the only one

The mainstream

Neighbour

Broadcaster bullying of cyclists

Traffic Droid

Sherry

Jeremy

Attack

A voice of concern

Q and A

The Battle of Kensington

The force

Disruptors

Successful trial

From 0 to 15 thousand

Fix the justice system

An envious cop

Record, retreat, report

The masses

When the feedback works

Granny

Adolescent boys hate women on bikes

Prove you’re not a camel

Too many to mention

The unspeakable

The Bush and the Corner

Snakes and Turtles

The language

Behind the wall

Is there Hope?

Acknowledgements

Figures

Index

Endnotes

Let’s clean the path

Is it cliché to claim that writing a book was a life-changing journey? Well, I will say it anyway. It transformed me. This book is deeply personal, even though I have tried to keep my distance and objectivity. Yet, while working on it, I found that I was not that unique at all. My experiences, observations and feelings are surprisingly common. Millions of people in the UK are victimised, bullied and harassed by motorists’ entitlement and road crime. Tens – if not hundreds – of thousands have resolved to resist, in the form of third-party reporting – the main topic of this book.

In these pages, you will have a chance to meet people who influenced that phenomenon. But you may notice that it exists in its own right. It doesn’t depend on any one of those people. Nothing would change if Mikey, Lewis or Jeremy put their cameras down tomorrow. There will still be an unfathomable number of others uploading videos of dangerous drivers to the police. It has reached a critical mass, and it cannot be stopped, no matter how many salty crocodile tears might flow down offenders' cheeks.

The research wasn’t too challenging. On the contrary, it was more difficult to filter sources and stick to the main topic. To achieve that, we must clarify several things:

First, this book is purely about third-party reporting. We may touch on the topics of active travel, car dependency, climate change, or fifteen-minute cities, or any other headline-worthy theme. But it won't be a full study of those issues. It would be a disservice to investigate them without proper attention and distraction from the main mission of the book.

Secondly, cycling will not be our primary interest, and neither would I claim to portray everyone who chooses to travel on two wheels, drive or walk. Bikes are central to this story because the media have built a narrative about this vehicle. The story would be different if we had the same uproar about drivers using dashcams. But as it affects our topic, we will dive a bit into what seems to be an engineered hate towards cyclists, who nowadays seem to be the only group that can be publicly dehumanised and harassed without severe consequences. However, it will be a generalised survey of the issue, and will focus mainly on the link to third-party reporting.

Thirdly, I hope some of you do not agree with me and my guests. Presenting their perspective is in itself a success to me. Even if you do not change your mind about these things, it will at least mean you are open to a dialogue rather than further hate and “footballisation”. We may need to debunk typical cliches like road tax, red light jumping, riding in the middle of the road and the benefits of hi-viz and helmets – but we will do it briefly. Some indeed require clarification. To tackle the first of these, I had to send an FOI[ii] request to HM Treasury to disprove the claim that there is a hypothecated[iii] road tax. There is no such thing.

The fourth thing I shall move out of our way is the personal views of my guests. They were chosen because of their value to the story. Some of them hold very controversial positions on other topics. Reaching out to several resulted in an uproar on social media. Perhaps it was for valid reasons, but what sort of study would it be without the core influencers? A car driver crashing into a pedestrian rarely has the luxury of asking them who they vote for or what they think about identity politics.

The Fifth and last thing is me. It may seem incredible to be immersed in the story and be both a narrator and an extra (surely not a lead). I will share my tale with you, but it only matters because I’m involved in the reporting. Anything else is just a distraction. I knew that my position would be both a blessing and a curse. Writing under my real name was tough, but controlling the information was simpler than containing the spillage. I learned that the hard way. And I will come back to that; I promise.

Let’s clarify: I have skin in the game on all fronts. I am a cyclist, riding with a video camera and with close to a thousand reports of traffic offences. I am vocal about road travel. I wear an Evil Cycling Lobby jumper in the office and support colleagues who commute on the bike: “That’s Lukasz from the bike shed. He’s famous!” one reporter said the other day when we met in the pub, causing consternation for my colleagues.

At the same time, I am a driver with a few decades’ experience of being behind the steering wheel. I understand the value of some motor usage. I am also an immigrant – and yes, this argument is used against me regularly – assimilated, tax-paying, and owning a black passport (it is not blue, is it?).

I work in the media, and that fact triggered many people to cancel me on Twitter in the early days. Being a journo is an excellent reason to be blocked. But I am not a reporter. I am an engineer. But okay, I get it. The media in the UK needs a better track record regarding the topic being discussed. Even the Evening Standard with Ross Lydall and the Guardian with Peter Walker, both with massive contributions to road safety, can publish jaw-droppingly wrong, click-bait titles fuelling further aggression towards cyclists or ignorance of the damage caused by drivers. What matters to me is that I can voice my beliefs as long I stay professional. Trust me, I have been to places where alternative opinions were not welcome.

As the path is clear now, I shall make the tone less formal with more contractions and tend to the story. I hope you’ll enjoy it.

A land of snitches

In the eyes of Telegraph columnist Celia Walden, the United Kingdom has become a country of snitches.[iv] Writing in the context of the 2020 lockdown, she ridiculed people reporting barbecues, sleepovers, or laughs. Then she moved to Mike van Erp’s[v] video that landed Guy Ritchie a six-month driving ban. When she wrote, “There’s one thing I loathe more”, I couldn’t work out if she meant dangerous drivers or those who report them. Perhaps, as a non-native speaker, I missed the subtlety of her statement. However, the ambiguity raised a crucial question. What do we despise more, wrongdoing or standing up to offenders? Does it depend on one’s role in the event? Is it about our history, background, or pre-existing affiliations? Would we report a burglar? What about a drunk driver? What about someone who passes a cyclist close enough to scare them but does not kill?

I sat on a crowded bus in central Warsaw and realised that Walden might have been onto something. On the Warsaw streets were a greater number of drivers glued to their screens than in London. In 2021, in Poland, there were almost twice as many road deaths per million inhabitants as in the UK (Poland 2,245[vi] per 38 million – 59; UK 1,158[vii] per 63 million – 24). It is such a frightening fact that it has been used as the opening to the fantastic book Watching the English by Kate Fox.[viii] She remembered a day when she drove with her husband to a wedding. At first, she noticed drivers pulling onto the hard shoulder to let others overtake them. She thought that was extremely polite and considerate. Her spouse quickly pointed to the number of crosses and shrines left on the roadside. Each marked a fatal collision. Yet, third-party reporting doesn’t exist in that country.

If you look at the media headlines and figures, the UK is a world leader inthird-party reporting – where the public forwards the evidence of crime or offence to the police. Why is it so? Why not the United States or China, where most of the technology used in our cameras is developed? Why not Australia, where, some say, the first headcam cyclists appeared? Why not the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, or France, which have a much larger number of commuter cyclists, so there is a greater chance for tension as well?

Is snitching a profoundly British thing? Is it a fault or a national virtue? It may originate from the values and institutions of the country and its legal system.

“The police are the public, and the public are the police.”[ix]

We could consider plenty of factors, but Peel’s Nine Principles of Policing by Consent, the pillars of British law enforcement, could be the most important. The common understanding is that this model regards police officers simply as citizens in uniform – nothing more. That fact alone changes the dynamics of society. Bobbies are not untouchable demigods like in other countries. The second fundamental change suggested by Peel was that a force’s success is measured not by the number of arrests but by the absence of crime. Last but not least, principles require the police to seek public approval and cooperation and actively encourage it. That is a reason for third-party reporting to exist.

The method is rare. Except for the UK, it’s applied only in Ireland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. While Peel is credited for the principles, they seem to have different authors. Historians suggest that they were created by joint commissioners of the newly formed Metropolitan Police, Charles Rowan and Richard Mayne, who were inspired by Peel’s speeches.

British people have a unique relationship with law enforcers. It’s unlike the rest of the world. At least it used to be, as some authors claim,[x] forces have more recently turned into paramilitary organisations far from the cherished bobbies-on-the-beat.[xi] In what other country can one approach an officer and challenge them without being arrested (or shot)? Nothing stops us from approaching a police van and saying, “Sir, can you please turn off the engine while parked?” Many officers don’t know it’s illegal to keep the engine idling. You can check that in the Highway Code, rule 123,[xii] and associated legislation.[xiii],[xiv]

One can file Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to scrutinise a local force or prove that drivers are the biggest group of third-party evidence submitters. We have a community speed watch. Many patrols involve special constables.[xv] Except in airports, embassies, and a few other places, you won’t see police carrying firearms.

Diplomatic units are particularly bad with traffic law. They had a habit of parking in front of my office, on the double yellow lines, blocking the visibility of the junction and pedestrian crossing ahead. After months of chasing them on social media, they finally stopped doing that. Can one achieve such a result anywhere else?

Let’s not forget that police commissioners are elected by the people as well. That is, except in Scotland. The power the public has over law enforcement seems unprecedented, yet very few Brits know or value that fact. On the contrary, many still see cooperation with the force as collaboration with a fascist regime. Such over-dramatised narrative often has very high-profile sources: Jeremy Clarkson dwelled on the topic with a level of fashion fetish:“Like the Stasi never went away. It even comes with a sinister uniform. Black shorts over black tights, a lemon-green shirt, and a surveillance camera on your head. It's like the Stasi never went away”,[xvi] he wrote in his Sun column. Katie Hopkins, in a post after visiting imprisoned ex-BBC presenter Alex Benfield, convicted of four accounts of stalking,[xvii] wrapped up her tweet with the #bikenonce hashtag.[xviii] It was received as a reference to one of the stalker’s victims – Jeremy Vine. It is no surprise that following such name-calling pornography, some people feel entitled to call concerned citizens a snitch, nonce, grass, squealer or rat – all of it prison slang.

We have to put up with tirades of hate from jail-inspired minorities. Despite that, people are still willing to spend their time and energy on third-party reporting. But why? It cannot be only because they can, right? What motivates them? There is something specific about the setting – our roads.

And no, it’s not about the way they are built. Neither is it because we drive on the left.[xix] Except for strange experiments like Stevenage, we don’t have wide alleys like Central or Eastern Europe – nor even wider multi-lane roads as in the US. There is much less space to put cycle lanes or widen the pavements. Our streets are narrow and clogged with parked cars, overgrown hedges, wheelie bins and other things, primarily SUVs, struggling to pass. As for their layout, British high streets look more like those in the Netherlands or Denmark. They also have hills, and wind, and the rain is worse over there. Car ownership is as significant, yet they chose a different approach. If it’s not about the roads as such, perhaps it’s about how we (do not) share them?

Many drivers don’t comply with, or know, for that matter, about recent changes to road hierarchy.[xx] Good luck using the new H2 rule when crossing a side street in Kensington. You’ll likely end up on a cab’s bonnet if you're not filming. During one of my road crossings early in January 2024, I was centimetres from being mown down by a van driver. I tried to cross a side street and instead of letting me go, he sped up. That was the third event like that in a week, so I decided to cross with a camera turned on. Video from the event gathered 1.5M views on X before it was taken down as the Met decided to prosecute the driver. My manner of crossing was rightly criticised – including by Daniel ShenSmith, a.k.a the Black Belt Barrister.[xxi] I agreed with that, in a follow-up recording describing infrastructural issues at the junction.[xxii] Yet the event was far from uncommon to the local authorities – who, to my understanding, choose to ignore it. In private chats with the local police, when asked about the crossing’s safety, the only answer I got was a shrug and a mention of “no resources”.

In many developing countries, a car still symbolises social status. In the UK, it’s an outdated symbol of freedom. One can remember only two situations in recent history when so many people tried to shield their rights as laid down in the Magna Carta: during the 2020 lockdown and when the update to the Highway Code was introduced. The H2 rule wasn’t changing anything but making rules 170[xxiii] and 180[xxiv] more transparent to the drivers. Not complying with them means failing the driving test. Yet, from behind the steering wheel, everyone seems to be in your way, an obstruction, a nuisance. Even the legal system seems to see it this way. Collecting 78 penalty points (most sources state 68, but even the original article contains both figures[xxv]) and still holding a driving licence is possible.[xxvi] According to the Sun, over 10,000 drivers with over 12 points on their licence were spared the ban in 2019. Exceptional hardship is being used as a get-out-of-jail-free card, and causing death by dangerous driving may often end with a suspended or no sentence. Cycling UK research in 2021 revealed that more than 8,000 drivers escaped the ban by using that argument.[xxvii] Between 2017 and 2021, the total number was 35,569. That is one in five (142,275 who received the ban).[xxviii] It doesn’t make exceptional hardship very exceptional, does it? In recent UK history, every single person who killed someone while cycling was found and jailed – I will talk about the exception in the chapter “Fix the justice system”. But there were 7,708 hit-and-run collisions in 2021 in London alone, in which at least 167 people died.[xxix] Many of those events end up without the culprit being found or named. Even the person who drove their Land Rover into a primary school in Wimbledon, killing two girls and seriously injuring others, is unknown to the public today.[xxx] It feels like murder or manslaughter is legal in the UK as long as a car is the weapon.[xxxi]

London may be the safest place to cycle in the whole of Europe. Yet the lack of consistent infrastructure throws cyclists into heavy traffic or onto the pavements. And the legality of pavement cycling is more complex than it may seem, with the Highway Code and various memoranda contradicting each other. Women are exceptionally at risk. One woman died on the day I edited this chapter. In rural settings it’s even worse, with relatively narrow and bendy roads, often with hedges limiting visibility and with high speeds allowed.[xxxii] Who sticks to the speed limit anyway? Almost half the drivers surveyed by the RAC admitted ignoring it.[xxxiii] Even former Home Secretary Suella Braverman made headlines for allegedly trying to dodge points for speeding by arranging a private awareness course.[xxxiv]

The problem is broader than cycling vs driving. Being a pedestrian in the UK is stressful and plain dangerous. On the one hand, there are no jaywalking laws,[xxxv] but there are also very few safe crossings. A dropped curb or pedestrian aisle aren’t legally a crossing. Each zebra requires a Belisha beacon, so drivers understand what the crossing means. That massively increases their cost and is something rather tricky to comprehend for a driver from the continent. Pavement parking is endemic, and parents with prams or people with disabilities must often enter the road to pass. That ends in tragedies. Try to ask a driver to give you more space and prepare for a saucy response or an assault. Funnily enough, pavement parking is illegal in London, but the law is hardly ever enforced. Scotland introduced a pavement parking ban recently, but we are still to see it working in practice. And we have only mentioned situations where the pedestrian must enter the road. Trevor Bird, 52 was walking with his 24-year-old son from the local social club, when the driver of a blue BMW mounted the pavement and hit them. The father died on the spot, while the son was taken to hospital with severe head injuries.[xxxvi] Between 2005 and 2018, 548 pedestrians were killed by vehicles on the pavements: that’s 40 a year. Out of 548, six of them were killed by cyclists.[xxxvii]

In such a vile environment, given the legal and practical tools, it was only a question of when, not if, people would take things into their own hands. And they did. Only recently has third-party reporting been focused on drivers using mobile phones. It all started with close passes, near hits, cutting in front of the rider, and pulling out without checking.

The media picked the term vigilante to label people using this system. But it’s not what that word means. At least not if you check in the dictionary.

vigilante – a person who tries in an unofficial way to prevent crime or to catch and punish someone who has committed a crime, especially because they do not think that official organisations, such as the police, are controlling crime effectively. Vigilantes usually join together to form groups.[xxxviii]

A vigilante enforces justice. But that’s not what reporting is. It’s the act of being a witness. Police, the Court Prosecution Service (CPS), and courts enforce the law. If Mike van Erp, David Brennan or Dave Sherry were vigilantes, they’d go full-blown Judge Dredd, knocking mirrors and windscreens. It is just another label, the same as lycra louts, cycle zealots, bike nonce, etc. Dehumanising and slurring. At the same time, people who demolish public property instead of common criminals can be called blade-runners![xxxix] Do they know Harrison Ford is an avid cyclist?[xl] This othering is going hand in hand with driver entitlement. It boils down to and comes back to us as real-life direct attacks, harassment or assaults. Some of the stories I’m about to tell you seem surreal, yet they happened. What was the trigger? The mere fact that the person dared to ride a bike on a road.

If all of that was not enough for people to fight back, then what is? Of course, we can raise the question of those who confront drivers or start looking out for offenders. I’ve been there. I know how it feels and the toll it takes. But is it a root problem, a symptom, or a cry for help? Desperation is a last resort when the state and society do not do enough to protect the vulnerable.

Cycling has become more inclusive, and the average cyclist in the capital no longer fits the image of the 20-30-year-old white male. This is the same for third-party reporting. The reasons that most known and popular reporters match the old stereotype is that ladies, ethnic minorities and LGBTQ+ people experience far more violence and abuse. They prefer to stay unnoticed. Most people using third-party reporting services are in fact drivers,[xli] yet the cyclists get the beating. You’re unlikely to risk more of that if you’re already targeted.

It’s easy to smear someone by calling them a grass. It’s simple to play whataboutery, referring to red light jumping and not wearing a helmet. It’s more challenging to take responsibility for one’s actions or inaction. It’s harder to admit that we may be part of the problem. Our lack of patience or empathy can cause not only someone else’s anxiety, but it can also kill them. And killing is one of the things motoring does best.

What we, and Walden, should hate are not those snitches but the bullies many people turn into when they sit down behind the wheel.

Pioneers

It was January of 2023. A few months earlier, my first book had come out, and I started to think about what to do next. While it was just a indie publication, it was a great lesson. It quickly taught me what I had done wrong, from ignoring promotion to not investing enough time and effort in quality. My thoughts were racing back and forth between the book, work, family and my third-party reports. There weren’t many in the previous year, just 35. Almost ten times fewer than in 2019. The process wore me down and I desperately wanted to change something. I tried to commute safely and to have a clear conscience that I was still doing something whilst not stealing precious time from my closest family and friends.

It was some random argument on X that did it: “Loads of drivers on phones. Won’t be able to report all captured. But the guy who later parked on zigzags suggested he can stab me for sure.”[xlii] In a typical comment from a football-themed profile, Mac Bennet asked, “Do you have a job and/or a life? Genuinely curious.”[xliii] It irritated me: “I work as a senior level manager and engineer. Have friends, family, and life. Many hobbies. Wrote a book. Enough?” “Pleasantly surprised”, he replied. I was astonished. I’d expect some further rant, but Mac left it there. He left me with a thought. It’s all his fault ;-)

The rest of the evening I spent googling for any previous publications on the topics of headcam cyclists and third-party reporting. No luck. That was my next challenge. That was a story I wanted to tell. A format I had never tried to write in my adult life,[xliv] it required research on a new scale. Finally, I had a way of channelling my selfish inner desire to have a positive impact.

If we had to define the mission of this book – even if I fail to deliver – we could say it’s to answer the question of why people resolve to third-party reports. Is it useful? Is that correct? Does it make a difference? Does it save lives? Is it a growing or a declining phenomenon? Is there an alternative? What’s the point? Can I even answer those questions? Or at least suggest some ideas?

To arrive there, we must start from a different angle: How? How did it begin? How and why did people decide to take things into their own hands? How is it possible for the police to delegate some of their responsibilities to the public? Who was the first to use a camera to defend themselves against dangerous drivers? Whose video was the first that resulted in actual prosecution?

Understanding how we got there could help us arrive at plausible reasoning. On a personal level, I might understand better why I joined the cause. Why can't so many of us leave our homes without a camera now?

The idea was not to draw any specific outline before at least half of the planned interviews were concluded. At best, I knew I wanted to tell the story chronologically. Who was there first?

It turned out that it was the camera.

In the beginning, there was a camera

Third-party reporting, as we know, requires evidence in the form of a photo or a video. To capture that footage, we need a device. Nowadays, we are spoiled with choices, from expensive GoPro and Insta360 to affordable ChilliTech or no-names from Alibaba or eBay. Plenty of pedestrians use their mobile phones to record events. Drivers equip their cars with NextBase, Vantrue, Garmin, Thinkware, or other competitive solutions. Many modern cars have them built in by default.

Where do the famous headcams used by many cyclists come from? That topic was presented in detail in an article by Zach in Pelvy,[xlv] so I’ll sum it up: In the early 1960s, skydiver Bob Sinclair attached his gyro-stabilized camera to a football helmet and shot his jumps for the Ripcord show. Not much later, NASA modified the Hasselblad 500c and used them in space. F1 driver Jackie Stewart started putting his Nikon camera on his helmet to get stills from his drives. Later, he had a full-blown camera bound to one side of his head and a massive battery on the other.

The technological breakthrough came in the 1980s with the Canon Ci-10 pocket-size camera, which, with an inventive connectivity hack by Aerial Video Systems, allowed first-person broadcasting on air for the first time. For bikes, Mark Schulze mixed up a heavy VHS cam and a VCR set-up in his backpack. Later experiments involved a high-frame-rate CritterCam by Greg Marshall.

The real change came with the introduction of the GoPro camera. To this day, it’s synonymous with recording cycle rides. In the early 2000s, Nicholas “Nick” Woodman, during his adventurous, adrenaline-seeking trips to Australia and Indonesia, formed an idea of a light, waterproof action camera that could also be affordable. He found a proper base for his prototype, arranged manufacturing in China, and went on a selling spree for his first mechanical, analogue, waterproof photo camera. His success in 2005 allowed his team to launch the first digital recorder the very next year. It was simple, rudimentary, and limited.

The tool found its purpose in 2006. They might not have been the first to record dangerous driving, but they will be the earliest history will remember. I’ll come back to it shortly.

Since then, modern commuters have been spoilt for choice. It’s still a niche digital market, and the key players don’t change often. Outside GoPro, others worth mentioning are Insta360, ChilliTech, Drift, Cycliq, Technalogic, Akaso, and Garmin. They vary greatly in terms of resolution, battery lifetime, durability, price, and more.

The platform

Since 2006, more and more people have had access to light, portable cameras. Their videos have to go somewhere. Initially, the clips weren’t about road danger; instead, they were made to show the fun side of rides. In the UK, the place that first gathered enthusiasts was the Cycling Plus forum. Eventually, videos started to land on YouTube, where they were accessible to the broader public.

The YouTube platform was founded in 2005 by three ex-PayPal employees: Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim – and was bought by Google sixteen months later. It was the birthplace of many phenomena, and bike-ride clips were just one of them. More and more viewers were attracted by footage of deadly situations from roads worldwide, with Russian dashcam footage becoming a gold standard of horror. Bike rides were still a tiny drop in the ocean, yet they attracted constantly growing audiences. YouTube, though, wasn’t a suitable medium for general communication and virtual hanging out. Twitter[xlvi] took on that role, gathering everyone interested in the abundance of topics and playing a prominent role in scaling awareness. It attracted the haters and trolls as well. After Twitter’s massive success in the United States, the platform became important in the UK. It was the place where everyone had to be. Institutions and media followed. So did the headcam cyclists.

The Croydon Cyclist maintained a list of riders with cameras from all over YouTube.[xlvii] By 2012, it included 473 British helmet-camera users, and also:

American (86)

Australian (33)

Canadian (15)

Dutch (12)

German (10)

Others (725 in total, 43 unassigned).

The oldest still online is “A Ride through Clyde Tunnel”,[xlviii] recorded by Magnatom[xlix] on June 29th 2006. Afterwards, Penticle uploaded “French recumbent ride”[l] on July 10th. The third was “Commute to work – new helmet cam”[li] by Andrew Bennet[lii] on August 27th.

It did not take long for those leisure rides to be replaced by close calls: “Almost doored”,[liii] October 6th 2006, when Andy Bennet was inches from being taken out by an SUV driver who did not check the road before opening the door, and “Bus vs camera”,[liv] February 6th 2007, when Magnatom was tailgated and pushed by a local bus driver – the event which landed him in the local papers.

No matter who I asked, those names popped up each time. Who was the first? David Brennan and Andrew Bennet. I failed to contact Andrew, despite trying to reach every Andy, Andrew, Andrei, and Andrey Bennet I could find on X. After documenting the new cycle infrastructure in Vauxhall in 2015, he stopped posting bike rides and replaced them with diving footage. On the other hand, David remained active and eager to help me tell this story.

As the hills wrapped the Firth of Forth when I rolled towards his home, David Brennan’s homeland became a bracket for this tale.

Magnatom

When I approached interviewees for this book, David was the first to respond, eager to share his experiences. Yet he remained humble throughout. The day after my memo, he replied with a lengthy letter outlining his journey through the years using the camera on his rides and beyond. David doesn't claim to be the first, and points at Andy instead. When it came to prominence, he left himself far behind other pioneers and has put far more limelight on Mike van Erp – the famous Cycling Mikey. They both began simultaneously on the Cycling Plus forum, sharing and discussing their footage. “Mikey always seemed to have a better camera than me!” David observed.

In both his writing and in person, there is something remarkable about David’s spirit. Brennan strikes you as having outstanding drive, pushing himself towards new goals, usually for the greater good. The first article mentioning his name, in 2004, described how, while at Glasgow Southern General Hospital, the young scientist co-ran research debunking the common misogynistic belief that women are worse than men at reading maps.[lv] At least, that’s what the editorial spin was. In fact, his team confirmed that both sexes used the same regions of the brain linked to map-reading ability. That instinct took this bright lad into a battle one-on-one with road violence and grew into an idea for a national movement (literally) under the name “Pedal on Parliament”. He managed to materialise that idea with the help of six friends. It may be, as he says, his “scientific brain” or “strong sense of justice”.

It was on the commute to his place of work that he experienced the brutality of the roads. And it didn’t make it any better that they led through picturesque Scottish landscapes.

On one occasion, he was passed by a van driver extremely close. He decided not to let it slip away but called the police, providing the plates. “They were decent enough and spoke to the driver,” he said, but they couldn’t do anything more without witnesses or evidence. A a light bulb in Dr Brennan’s brain lit up. “A camera was the answer.”

It was a remarkable coincidence that Oregon Scientific released a “cheap camera”, as David called it. Yet it took him some time to collect funds to afford the purchase. Would that stop him? Not at all. He strapped his mobile phone to his backpack and recorded the ride through the Clyde Tunnel – the first YouTube uploaded. When asked about what he felt back then, he said: “It felt wrong that I could be placed in danger on the roads with absolutely no recourse if something happened.”

The camera was helpful not only when dealing with the police but also when the footage was shared on the forum. David received a lot of feedback. “Much of it was positive and supportive, some of it was negative. Not abusive at that time, at least not initially, but some people would scrutinise every single detail of the situation and question my cycling. Whilst that was surprising to me, it was actually informative. It taught me to always question my actions and my motivations. It taught me to realise that, yes, sometimes I was in the wrong and to learn from that and try and improve. So, I've always been willing to listen to criticism so long as it was genuine and not abusive.”

In the beginning, David’s actions started to offer a lot of hope. After several scary incidents with bus drivers, First, a local bus operator, agreed to his suggestion to run a safety campaign. In an interview for Metro, Glasgow Edition, David said,[lvi] “I've got a camera in my helmet and, after an incident this year, I sent the video to First with suggestions they should start a drivers' campaign. I was amazed when First contacted me to say it would agree to the campaign.” It was called “Give Cyclists Room” and was supposed to involve stickers inside the cabins of thousands of buses reminding drivers to give cyclists room and to enforce the message at safety briefings. It was a success with a sour aftertaste. The bus drivers did not appreciate being scrutinised. The hate campaign started to stem from their informal forum BloodBus, where conspiracy theories began. Most – like an accusation that David cycles because of losing his licence through drunk driving – were very quickly debunked and shut down.

The tension was great enough to throw Magnatom into the pages yet again. The Sun named him a “Tapped Crusader”[lvii] and suggested that his reports led to several bus drivers being sacked. David was approached by STV and managed to pass on his message after the Sun went on a three-day spree about him. “I am not out to antagonise anybody. I am trying to convey the message that all road users should be equal and that there should be more respect on the roads. As a cyclist, you get a lot of abuse on the roads. It's about mutual respect, and road users need to integrate better.”[lviii] On the last day, the paper columnist John Smeaton tried his worst to trivialise David, calling him “Ped-Al Qaeda”[lix] and listing a series of nonsensical myths about cyclists. To the claim that third-party reporting causes hatred towards cyclists, this is my riposte: It doesn’t. That hate was already there.

Magnatom wasn’t alone in his sentiments about road safety. The same week, when the Scottish Sun released their tirade, Fiona Russell recollected her experience in the pages of the Guardian.[lx] She presented a fairer image of David and mentioned other successes of headcam use in the UK. Winchester-based Paul McNeil[lxi] pursued his claims after a collision on his way to work. He was one of hundreds already wearing a camera. As Russell reported, Action Cameras, one of the UK’s leading sellers, experienced a threefold rise in sales in 2008. That meant an average of 50 per week for commuters.