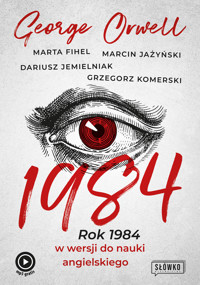

Animal Farm. Folwark zwierzęcy w wersji do nauki angielskiego ebook

George Orwell, Marta Fihel, Marcin Jażyński, Grzegorz Komerski

Uzyskaj dostęp do tej i ponad 250000 książek od 14,99 zł miesięcznie

10 osób interesuje się tą książką

- Wydawca: MT Biznes

- Kategoria: Języki obce

- Język: polski

Język angielski

Poziom B1-B2

Lubisz czytać dobre powieści a jednocześnie chcesz doskonalić swój angielski?

Mamy dla Ciebie idealne połączenie!

Klasyka literatury światowej w wersji do nauki języka angielskiego.

CZYTAJ – SŁUCHAJ - ĆWICZ

CZYTAJ – dzięki oryginalnemu angielskiemu tekstowi powieści Animal Farm przyswajasz nowe słówka, uczysz się ich zastosowania w zdaniach i poszerzasz słownictwo. Wciągająca fabuła książki sprawi, że nie będziesz mógł się oderwać od lektury, co zapewni regularność nauki.

Czytanie tekstów po angielsku to najlepsza metoda nauki angielskiego.

SŁUCHAJ – pobierz bezpłatne nagranie oryginalnego tekstu dostępne na poltext.pl/pobierz. Czytaj jednocześnie słuchając nagrania i utrwalaj wymowę.

ĆWICZ – do każdego rozdziału powieści przygotowane zostały specjalne dodatki i ćwiczenia

- na marginesach stron znajdziesz minisłownik i objaśnienia trudniejszych wyrazów;

- w części O słowach poszerzysz słownictwo z danej dziedziny, a w części gramatycznej poznasz struktury i zagadnienia językowe;

- dzięki zamieszczonym na końcu rozdziału testom i różnorodnym ćwiczeniom sprawdzisz rozumienie przeczytanego tekstu;

- odpowiedzi do wszystkich zadań zamkniętych znajdziesz w kluczu na końcu książki.

Przekonaj się, że nauka języka obcego może być przyjemnością, której nie sposób się oprzeć.

POSZERZAJ SŁOWNICTWO – UTRWALAJ – UCZ SIĘ WYMOWY

Jak pisał Orwell: Mój morał brzmi - rewolucje mogą przynieść radykalną poprawę, gdy masy będą czujne i będą wiedzieć, jak pozbyć się swych przywódców, gdy tamci zrobią, co do nich należy. [...] Nie można robić rewolucji, jeśli nie robi się jej dla siebie; nie ma czegoś takiego, jak dobrotliwa dyktatura."

***

Marta Fihel - anglistka, nauczycielka z wieloletnim stażem. Współautorka książek do nauki języka angielskiego i słowników.

Marcin Jażyński - doktor filozofii UW. Zajmuje się kognitywistyką, reżyseruje filmy animowane. Współpracuje z Collegium Civitas oraz Gimnazjum Społecznym w Milanówku. Uczy filozofii, logiki i filmu animowanego.

Prof. dr hab. Dariusz Jemielniak – wykładowca w Akademii Leona Koźmińskiego. Pracował jako tłumacz agencyjny i książkowy, współautor kilkunastu podręczników do nauki języka angielskiego, twórca największego polskiego darmowego słownika internetowego ling.pl

Grzegorz Komerski - absolwent filozofii, tłumacz, współautor książek do nauki języka angielskiego.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Liczba stron: 282

Rok wydania: 2021

Odsłuch ebooka (TTS) dostepny w abonamencie „ebooki+audiobooki bez limitu” w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Popularność

Podobne

Koncepcja serii: Dariusz Jemielniak

Redakcja: Jadwiga Witecka

Projekt okładki: Michał Duława

Grafika na okładce: copyright © Nantia.co

Skład i łamanie: Protext

Opracowanie wersji elektronicznej:

Nagranie, dźwięk i opracowanie muzyczne: Grzegorz Dondziłło, maxx-audio.com

Lektor: Mark Fordham

Copyright © 2021 by Poltext sp. z o.o.

Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone. Nieautoryzowane rozpowszechnianie całości lub fragmentów niniejszej publikacji w jakiejkolwiek postaci zabronione. Wykonywanie kopii metodą elektroniczną, fotograficzną, a także kopiowanie książki na nośniku filmowym, magnetycznym, optycznym lub innym powoduje naruszenie praw autorskich niniejszej publikacji. Niniejsza publikacja została elektronicznie zabezpieczona przed nieautoryzowanym kopiowaniem, dystrybucją i użytkowaniem. Usuwanie, omijanie lub zmiana zabezpieczeń stanowi naruszenie prawa.

Warszawa 2021

Poltext Sp. z o.o.

www.poltext.pl

ISBN 978-83-8175-260-2 (format epub)

ISBN 978-83-8175-261-9 (format mobi)

W wersji do nauki angielskiego dotychczas ukazały się:

A Christmas Carol

Opowieść wigilijna

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Alicja w Krainie Czarów

Anne of Green Gables

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza

Anne of Avonlea

Ania z Avonlea

Christmas Stories

Opowiadania świąteczne

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen

Baśnie Hansa Christiana Andersena

Fanny Hill. Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

Wspomnienia kurtyzany

Little Women

Małe kobietki

Frankenstein

Frankenstein

Peter and Wendy

Piotruś Pan

Pride and Prejudice

Duma i uprzedzenie

Sense and Sensibility

Rozważna i romantyczna

Short Stories by Edgar Allan Poe

Opowiadania Allana Edgara Poe

Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Collection

Opowiadania autora Wielkiego Gatsby’ego

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Doktor Jekyll i pan Hyde

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Part 1

Przygody Sherlocka Holmesa

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Part 2

Przygody Sherlocka Holmesa. Ciąg dalszy

The Age of Innocence

Wiek niewinności

The Blue Castle

Błękitny Zamek

The Great Gatsby

Wielki Gatsby

The Hound of the Baskervilles

Pies Baskerville’ów

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Portret Doriana Graya

The Secret Garden

Tajemniczy ogród

The Time Machine

Wehikuł czasu

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Czarnoksiężnik z Krainy Oz

Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog)

Trzech panów w łódce (nie licząc psa)

Wstęp

Ile znacie rzeczy, które można zrobić za pomocą języka? To źle postawione pytanie. Teraz zadamy je lepiej: ile znacie rzeczy, jakie można zrobić, źle używając języka? Znowu źle. Spróbujmy jaśniej i prościej. Jak użyć języka, żeby zrobić coś złego i to na długo? I to z wieloma zwierzętami, np. takimi jak my? Powiemy wam. Stopniowo. Nie wszystko naraz. Zło, żeby było prawdziwym złem, trzeba robić krok po kroku. Za pomocą języka. Skutecznie. Nie potrzeba policji ani wojska. Natomiast język jest niezbędny.

Na szczęście, język, coś, co nami włada, pozwala również władać sobą. Za jego pomocą można zrobić całkiem dużo dobrych rzeczy. Oczywiście, o ile jest się dobrym zwierzęciem.

George Orwell, a właściwie Eric Arthur Blair, przyszedł na świat 25 czerwca 1903 roku w indyjskim mieście Bengal. „Folwark zwierzęcy”, gorzka satyra na radziecki eksperyment społeczny, został po raz pierwszy wydany w 1945 roku. Obok „Roku 1984” książka stała się najpopularniejszym dziełem pisarza. Wartka fabuła angażuje uwagę czytalnika, a przekonujące postaci bohaterów budzą rozmaite emocje. Lekturze – szczególnie w wersji oryginalnej – sprzyja prosty i bezpretensjonalny język powieści. Zaś jej tematyka… no cóż, niestety, wciąż pozostaje niezwykle aktualna.

Opracowany przez nas podręcznik oparty na oryginalnym tekście powieści został skonstruowany według przejrzystego schematu.

Na marginesach tekstu podano

objaśnienia

trudniejszych wyrazów.

Każdy rozdział jest zakończony krótkim testem sprawdzającym stopień

rozumienia tekstu

.

Zawarty po każdym rozdziale dział

O słowach

jest poświęcony poszerzeniu słownictwa z danej dziedziny, synonimom, łącznikom i spójnikom,

phrasal verbs

, słowotwórstwu oraz wyrażeniom idiomatycznym.

W dziale poświęconym

gramatyce

omówiono wybrane zagadnienia gramatyczne, ilustrowane fragmentami poszczególnych części powieści.

Dla dociekliwych został również opracowany komentarz do wybranych zagadnień związanych z

kulturą i historią

.

Różnorodne ćwiczenia pozwolą Czytelnikowi powtórzyć i sprawdzić omówione w podręczniku zagadnienia leksykalne i gramatyczne. Alfabetyczny wykaz wyrazów objaśnianych na marginesie tekstu znajduje się w słowniczku. Odpowiedzi do wszystkich zadań zamkniętych są podane w kluczu na końcu książki. W kluczu znajdują się również przykładowe rozwiązania niektórych ćwiczeń, na które nie ma jednej poprawnej odpowiedzi. Są to ćwiczenia, które pomogą zwrócić uwagę Czytelnika przede wszystkim na to, jak się uczyć – jak tworzyć listy nowych wyrazów, jak je systematyzować i powtarzać.

A zatem: choć lektura „Folwarku zwierzęcego” nie należy do wesołych, życzymy ciekawej i pouczającej lektury!

Chapter 1

Słownictwo

Mr. Jones, of the Manor Farm, had locked the hen-houses for the night, but was too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes. With the ring of light from his lantern dancing from side to side, he lurched across the yard, kicked off his boots at the back door, drew himself a last glass of beer from the barrel in the scullery, and made his way up to bed, where Mrs. Jones was already snoring.

As soon as the light in the bedroom went out there was a stirring and a fluttering all through the farm buildings. Word had gone round during the day that old Major, the prize Middle Whiteboar, had had a strange dream on the previous night and wished to communicate it to the other animals. It had been agreed that they should all meet in the big barn as soon as Mr. Jones was safely out of the way. Old Major (so he was always called, though the name under which he had been exhibited was Willingdon Beauty) was so highly regarded on the farm that everyone was quite ready to lose an hour’s sleep in order to hear what he had to say.

At one end of the big barn, on a sort of raised platform, Major was already ensconced on his bed of straw, under a lantern which hung from a beam. He was twelve years old and had lately grown rather stout, but he was still a majestic-looking pig, with a wise and benevolent appearance in spite of the fact that his tushes had never been cut. Before long the other animals began to arrive and make themselves comfortable after their different fashions. First came the three dogs, Bluebell, Jessie, and Pincher, and then the pigs, who settled down in the straw immediately in front of the platform. The hens perched themselves on the window-sills, the pigeons fluttered up to the rafters, the sheep and cows lay down behind the pigs and began to chew the cud. The two cart-horses, Boxer and Clover, came in together, walking very slowly and setting down their vast hairy hoofs with great care lest there should be some small animal concealed in the straw. Clover was a stout motherly mare approaching middle life, who had never quite got her figure back after her fourth foal. Boxer was an enormous beast, nearly eighteen hands high, and as strong as any two ordinary horses put together. A white stripe down his nose gave him a somewhat stupid appearance, and in fact he was not of first-rate intelligence, but he was universally respected for his steadiness of character and tremendous powers of work. After the horses came Muriel, the white goat, and Benjamin, the donkey. Benjamin was the oldest animal on the farm, and the worst tempered. He seldom talked, and when he did, it was usually to make some cynical remark – for instance, he would say that God had given him a tail to keep the flies off, but that he would sooner have had no tail and no flies. Alone among the animals on the farm he never laughed. If asked why, he would say that he saw nothing to laugh at. Nevertheless, without openly admitting it, he was devoted to Boxer; the two of them usually spent their Sundays together in the small paddock beyond the orchard, grazing side by side and never speaking.

The two horses had just lain down when a brood of ducklings, which had lost their mother, filed into the barn, cheepingfeebly and wandering from side to side to find some place where they would not be trodden on. Clover made a sort of wall round them with her great foreleg, and the ducklings nestled down inside it and promptly fell asleep. At the last moment Mollie, the foolish, pretty white mare who drew Mr. Jones’s trap, came mincingdaintily in, chewing at a lump of sugar. She took a place near the front and began flirting her white mane, hoping to draw attention to the red ribbons it was plaited with. Last of all came the cat, who looked round, as usual, for the warmest place, and finally squeezed herself in between Boxer and Clover; there she purredcontentedly throughout Major’s speech without listening to a word of what he was saying.

All the animals were now present except Moses, the tameraven, who slept on a perch behind the back door. When Major saw that they had all made themselves comfortable and were waiting attentively, he cleared his throat and began:

“Comrades, you have heard already about the strange dream that I had last night. But I will come to the dream later. I have something else to say first. I do not think, comrades, that I shall be with you for many months longer, and before I die, I feel it my duty to pass on to you such wisdom as I have acquired. I have had a long life, I have had much time for thought as I lay alone in my stall, and I think I may say that I understand the nature of life on this earth as well as any animal now living. It is about this that I wish to speak to you.

“Now, comrades, what is the nature of this life of ours? Let us face it: our lives are miserable, laborious, and short. We are born, we are given just so much food as will keep the breath in our bodies, and those of us who are capable of it are forced to work to the last atom of our strength; and the very instant that our usefulness has come to an end we are slaughtered with hideous cruelty. No animal in England knows the meaning of happiness or leisure after he is a year old. No animal in England is free. The life of an animal is misery and slavery: that is the plain truth.

“But is this simply part of the order of nature? Is it because this land of ours is so poor that it cannot afford a decent life to those who dwell upon it? No, comrades, a thousand times no! The soil of England is fertile, its climate is good, it is capable of affording food in abundance to an enormously greater number of animals than now inhabit it. This single farm of ours would support a dozen horses, twenty cows, hundreds of sheep – and all of them living in a comfort and a dignity that are now almost beyond our imagining. Why then do we continue in this miserable condition? Because nearly the whole of the produce of our labour is stolen from us by human beings. There, comrades, is the answer to all our problems. It is summed up in a single word – Man. Man is the only real enemy we have. Remove Man from the scene, and the root cause of hunger and overwork is abolished for ever.

“Man is the only creature that consumes without producing. He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits. Yet he is lord of all the animals. He sets them to work, he gives back to them the bare minimum that will prevent them from starving, and the rest he keeps for himself. Our labour tills the soil, our dungfertilises it, and yet there is not one of us that owns more than his bare skin. You cows that I see before me, how many thousands of gallons of milk have you given during this last year? And what has happened to that milk which should have been breeding upsturdycalves? Every drop of it has gone down the throats of our enemies. And you hens, how many eggs have you laid in this last year, and how many of those eggs ever hatched into chickens? The rest have all gone to market to bring in money for Jones and his men. And you, Clover, where are those four foals you bore, who should have been the support and pleasure of your old age? Each was sold at a year old – you will never see one of them again. In return for your four confinements and all your labour in the fields, what have you ever had except your bare rations and a stall?

“And even the miserable lives we lead are not allowed to reach their natural span. For myself I do not grumble, for I am one of the lucky ones. I am twelve years old and have had over four hundred children. Such is the natural life of a pig. But no animal escapes the cruel knife in the end. You young porkers who are sitting in front of me, every one of you will scream your lives out at the block within a year. To that horror we all must come – cows, pigs, hens, sheep, everyone. Even the horses and the dogs have no better fate. You, Boxer, the very day that those great muscles of yours lose their power, Jones will sell you to the knacker, who will cut your throat and boil you down for the foxhounds. As for the dogs, when they grow old and toothless, Jones ties a brick round their necks and drowns them in the nearest pond.

“Is it not crystal clear, then, comrades, that all the evils of this life of ours spring from the tyranny of human beings? Only get rid of Man, and the produce of our labour would be our own. Almost overnight we could become rich and free. What then must we do? Why, work night and day, body and soul, for the overthrow of the human race! That is my message to you, comrades: Rebellion! I do not know when that Rebellion will come, it might be in a week or in a hundred years, but I know, as surely as I see this straw beneath my feet, that sooner or later justice will be done. Fix your eyes on that, comrades, throughout the short remainder of your lives! And above all, pass on this message of mine to those who come after you, so that future generations shall carry on the struggle until it is victorious.

“And remember, comrades, your resolution must never falter. No argument must lead you astray. Never listen when they tell you that Man and the animals have a common interest, that the prosperity of the one is the prosperity of the others. It is all lies. Man serves the interests of no creature except himself. And among us animals let there be perfect unity, perfect comradeship in the struggle. All men are enemies. All animals are comrades.”

At this moment there was a tremendous uproar. While Major was speaking four large rats had crept out of their holes and were sitting on their hindquarters, listening to him. The dogs had suddenly caught sight of them, and it was only by a swiftdash for their holes that the rats saved their lives. Major raised his trotter for silence.

“Comrades,” he said, “here is a point that must be settled. The wild creatures, such as rats and rabbits – are they our friends or our enemies? Let us put it to the vote. I propose this question to the meeting: Are rats comrades?”

The vote was taken at once, and it was agreed by an overwhelmingmajority that rats were comrades. There were only four dissentients, the three dogs and the cat, who was afterwards discovered to have voted on both sides. Major continued:

“I have little more to say. I merely repeat, remember always your duty of enmity towards Man and all his ways. Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy. Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend. And remember also that in fighting against Man, we must not come to resemble him. Even when you have conquered him, do not adopt his vices. No animal must ever live in a house, or sleep in a bed, or wear clothes, or drink alcohol, or smoke tobacco, or touch money, or engage intrade. All the habits of Man are evil. And, above all, no animal must ever tyrannise over his own kind. Weak or strong, clever or simple, we are all brothers. No animal must ever kill any other animal. All animals are equal.

“And now, comrades, I will tell you about my dream of last night. I cannot describe that dream to you. It was a dream of the earth as it will be when Man has vanished. But it reminded me of something that I had long forgotten. Many years ago, when I was a little pig, my mother and the other sows used to sing an old song of which they knew only the tune and the first three words. I had known that tune in my infancy, but it had long since passed out of my mind. Last night, however, it came back to me in my dream. And what is more, the words of the song also came back-words, I am certain, which were sung by the animals of long ago and have been lost to memory for generations. I will sing you that song now, comrades. I am old and my voice is hoarse, but when I have taught you the tune, you can sing it better for yourselves. It is called ‘Beasts of England’.”

Old Major cleared his throat and began to sing. As he had said, his voice was hoarse, but he sang well enough, and it was a stirring tune, something between ‘Clementine’ and ‘La Cucaracha’. The words ran:

Beasts of England, beasts of Ireland,

Beasts of every land and clime,

Hearken to my joyful tidings

Of the golden future time.

Soon or late the day is coming,

Tyrant Man shall be o’erthrown,

And the fruitful fields of England

Shall be trod by beasts alone.

Rings shall vanish from our noses,

And the harness from our back,

Bit and spur shall rust forever,

Cruel whips no more shall crack.

Riches more than mind can picture,

Wheat and barley, oats and hay,

Clover, beans, and mangel-wurzels

Shall be ours upon that day.

Bright will shine the fields of England,

Purer shall its waters be,

Sweeter yet shall blow its breezes

On the day that sets us free.

For that day we all must labour,

Though we die before it break;

Cows and horses, geese and turkeys,

All must toil for freedom’s sake.

Beasts of England, beasts of Ireland,

Beasts of every land and clime,

Hearken well and spread my tidings

Of the golden future time.

The singing of this song threw the animals into the wildest excitement. Almost before Major had reached the end, they had begun singing it for themselves. Even the stupidest of them had already picked up the tune and a few of the words, and as for the clever ones, such as the pigs and dogs, they had the entire song by heartwithin a few minutes. And then, after a few preliminary tries, the whole farm burst out into ‘Beasts of England’ in tremendous unison. The cows lowed it, the dogs whined it, the sheep bleated it, the horses whinnied it, the ducks quacked it. They were so delighted with the song that they sang it right through five times in succession, and might have continued singing it all night if they had not been interrupted.

Unfortunately, the uproar awoke Mr. Jones, who sprang out of bed, making sure that there was a fox in the yard. He seized the gun which always stood in a corner of his bedroom, and let fly a charge of number 6 shot into the darkness. The pellets buried themselves in the wall of the barn and the meeting broke up hurriedly. Everyone fled to his own sleeping-place. The birds jumped on to their perches, the animals settled down in the straw, and the whole farm was asleep in a moment.

Rozumienie tekstu

Klucz >>>

Uzupełnij zdania imionami z ramki. Dwa imiona zostały podane dodatkowo i nie pasują do żadnego ze zdań.

Benjamin, Bluebell, Boxer, Clover, Jones, Major, Mollie, Moses

1. Mr. …………………………………., who’s the proprietor of the Manor Farm, is a neglectful drunkard.

2. …………………………………., a tame raven, doesn’t take part in the animals’ assembly.

3. Old …………………………………., who is a prize boar, had an inspiring dream.

4. The strongest horse on the Manor Farm is …………………………………. .

5. …………………………………., the donkey, who is the oldest animal on the Manor Farm, is also bad-tempered.

6. The farmer’s carriage is usually pulled by …………………………………., a pretty, young mare.

O słowach

ANIMAL SOUNDS

“The cows lowed it, the dogs whined it, the sheep bleated it, the horses whinnied it, the ducks quacked it.”

Każde zwierzę śpiewało pieśń Beasts of England na swój sposób – krowy ryczały, psy skomlały, owce beczały, konie rżały, a kaczki kwakały. Poniższa lista zawiera te i inne czasowniki opisujące odgłosy, jakie wydają różne zwierzęta. Niektóre czasowniki mają kilka znaczeń i dlatego odnoszą się do bardzo odmiennych gatunków.

ENGLISH VERB

POLISH VERB

ANIMAL(S)

bark

szczekać

dog, fox, seal

bay

ujadać

dog

bleat

beczeć, meczeć

sheep, goat

bray

ryczeć, rżeć

donkey

buzz

brzęczeć

bee, fly

cackle

gdakać, gęgać

chicken, goose

chirp, chirrup, tweet, twitter

ćwierkać, świergotać

bird

coo

gruchać

pigeon

croak

rechotać; krakać

frog, raven

crow

piać

rooster

gibber

jazgotać, wydawać nieartykułowane dźwięki

ape, monkey

growl

mruczeć; warczeć

bear, dog, wolf, lion, tiger

grunt

chrząkać

pig

hiss

syczeć

cat, snake

hoot

pohukiwać

owl

howl

wyć

dog, jackal, wolf

low

ryczeć, muczeć

cow, cattle

meow, mew, miaow

miauczeć

cat

moo

muczeć

cow

neigh

rżeć

horse

purr

mruczeć

cat

quack

kwakać

duck

roar

ryczeć

elephant, lion, tiger

scream

przeraźliwie gwizdać, wrzeszczeć

hyena, monkey, peacock, seagull

screech

skrzeczeć, wrzeszczeć

bat, monkey, parrot

snort

parskać, prychać

horse, pig

squeak

piszczeć

mouse, rat, horse

squeal

piszczeć, kwiczeć

mouse, pig

whine

skomleć; brzęczeć

dog, mosquito

whinny

cicho rżeć

horse

Gramatyka

DOPEŁNIACZ SAKSOŃSKI Z OKREŚLENIAMI CZASU

“Old Major (…) was so highly regarded on the farm that everyone was quite ready to lose an hour’s sleep in order to hear what he had to say.”

Jeśli chcemy określić czas trwania danej sytuacji, możemy użyć konstrukcji z dopełniaczem saksońskim (’s), np.:

an hour’s break

godzinna przerwa

a year’s holiday

roczny urlop

a month’s sick leave

miesięczne zwolnienie lekarskie

a week’s journey

tygodniowa podróż

Jeśli dane wydarzenie trwa kilka godzin, tygodni, miesięcy itd., dopełniacz saksoński przyjmuje formę apostrofu (bez końcówki s), który umieszcza się po rzeczowniku w liczbie mnogiej, np.:

a two hours’ flight

dwugodzinny lot

a three years’ course

trzyletni kurs

a six months’ rehab

sześciomiesięczne leczenie odwykowe

a two weeks’ quarantine

dwutygodniowa kwarantanna

Dopełniacz saksoński z określeniami czasu pozwala też utworzyć formy typu dzisiejszy, wczorajszy, zeszłoroczny i inne wyrażenia sygnalizujące odniesienie do jakiegoś momentu, np.

They first met at last year’s aikido camp.

Poznali się na zeszłorocznym obozie aikido.

Yesterday’s values are being undermined.

Podważa się wartości, jakie obowiązywały wczoraj.

Have you checked tomorrow’s weather forecast?

Czy sprawdziłeś prognozę pogody na jutro?

Last year’s caretakers of the exotic island quit their well-paid jobs for what they regarded as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Opiekunowie egzotycznej wyspy z zeszłego roku rzucili dobrze płatne posady dla czegoś, co uważali za szansę zdarzającą się raz w życiu.

We’re all getting ready for next month’s charity concert.

Wszyscy przygotowujemy się do zaplanowanego na przyszły miesiąc koncertu charytatywnego.

Kultura i historia

LA CUCARACHA

La cucaracha (po polsku „karaluch”) jest piosenką, której melodię i tytuł znają niemal wszyscy. Utwór ten niezwykle często służy za tło dźwiękowe filmów rozgrywających się w Meksyku czy Hiszpanii, seriali, a nawet imprez tematycznych. Skoczne dźwięki La cucarachy niemal natychmiast przywodzą nam przed oczy czwórkę gitarzystów w olbrzymich sombrerach i czarnych strojach upstrzonych astronomiczną ilością cekinów. Rzadko jednak zastanawiamy się, o czym ta wesoła piosenka opowiada i jaka kryje się za nią historia. Przekonajmy się.

Nikt nie wie, kto skomponował melodię La cucarachy. Wiadomo jednak, że jest to utwór bardzo stary, z całą pewnością sięgający XV wieku, a niewykluczone, że czasów jeszcze dawniejszych. Wiadomo również, że La cucaracha należy do starego gatunku hiszpańskich ballad ludowych zwanych corrido, wywodzących się w prostej linii ze średniowiecznych pieśni rozpowszechnianych na miejskich rynkach i w arystokratycznych dworach przez bardów i minstreli.

Tematyka corrido obraca się zazwyczaj wokół zbrodni, miłości, zemsty i niedoli prostego człowieka. Ponieważ jednak są to utwory ludowe czy – jak powiedzielibyśmy dzisiaj – folkowe, wykazują silną tendencję do ewolucji. Kolejne śpiewające je osoby wprowadzają własne zmiany w tekście, dopasowując pieśni do własnego życia i własnych problemów.

Według jednej z wersji pochodzenia melodii, La cucarachę poznali Hiszpanie od arabskich żeglarzy w okresie walk o wyzwolenie Półwyspu Iberyjskiego spod panowania wyznawców Islamu (zwanych wtedy Maurami). Jedna ze starszych zachowanych zwrotek piosenki brzmi: De las patillas de un moro / tengo que hacer una escoba, / para barrer el cuartel / de la infantería española („Z bokobrodów Maura / muszę zrobić miotłę / bo trzeba pozamiatać koszary / hiszpańskiej piechoty”).

Inne wczesne wersje tekstu dotyczą rozmaitych momentów z historii: zdobycia Grenady, hiszpańskich wojen karlistowskich czy francuskiej interwencji w Meksyku.

No właśnie – krajem, w którym La cucaracha nabrała szczególnego znaczenia jest właśnie Meksyk, gdzie w czasie tzw. rewolucji meksykańskiej (1910–1920) piosenka ta stała się jedną z ulubionych pieśni żołnierzy generała Pancho Villi. Spośród niezliczonych odmian tekstu najbardziej popularną jest ta: La cucaracha, la cucaracha / ya no puede caminar / porque no tiene, porque le falta / marihuana que fumar. Ya murió la cucaracha / ya la llevan a enterrar / entre cuatro zopilotes / y un ratón de sacristán(„Karaluch, karaluch / nie może dłużej chodzić / bo nie ma, bo już nie ma / marihuany do palenia. Karaluch właśnie padł / i zaraz go pogrzebią / między czterema sępami / i kościelną myszą”).

W tej wersji piosenki tytułowym karaluchem jest prezydent Victoriano Huerta, uważany przez rewolucjonistów za zdrajcę i polityk słynący z przesadnego uwielbienia dla używek, zamieszany w śmierć popierającego rewolucję prezydenta Francisco Madero.

Nie mamy tu miejsca na szczegółowe opisywanie kolei meksykańskiej historii. Warto jednak wiedzieć, że rewolucja 1910 roku wybuchła po części z powodu niezadowolenia z niesprawiedliwego traktowania Meksyku przez wielkie, amerykańskie koncerny, lecz przede wszystkim jako wyraz sprzeciwu wobec rządów Porfirio Diaza, dyktatora sprawującego w kraju niepodzielną władzę przez długie 31 lat. Rewolucja prędko przeistoczyła się w długotrwałą i wielostronną wojnę domową, w której jednym z bardziej aktywnych uczestników byli finansujący aktualnych sojuszników Amerykanie. W 1913 roku dyplomaci USA zorganizowali zamach stanu, w efekcie którego władzę objął wspomniany prezydent Victoriano Huerta. To właśnie przeciwko niemu walczyli przywódcy partyzanccy w rodzaju słynnego Pancho Villi i Emiliano Zapaty.

Pancho Villa był i jest dla wielu Meksykanów po dziś dzień postacią w rodzaju angielskiego Robin Hooda, bohaterem ludowej wyobraźni. Niezliczone opowieści kreują jego obraz zatroskanego szarym człowiekiem, romantyka, któremu nieobce są uroki towarzystwa pięknych pań, a przede wszystkim osoby o nieskazitelnym honorze. Zwolennicy Villi wywodzili się głównie z wiosek i szli do walki z ludowymi piosenkami na ustach. Jedną z bardziej popularnych była właśnie La cucaracha.

Na zakończenie jeszcze jedna z wersji tekstu: Una cosa me da risa / Pancho Villa sin camisa./ Ya se van los Carranzistas / Porque vienen los Villistas („Jest coś, co zawsze mnie rozśmiesza / Pancho Villa bez koszuli. / Wojska Carranzy* uciekają / Nadszedł czas ludzi od Villi”).

* Generał Venustiano Carranza, jeden z przeciwników Pancho Villi.

Ćwiczenia

Klucz >>>

1.Połącz wyrazy 1–10 z ich synonimami, definicjami i opisami (A–J).

1. acquire

2. admit

3. barrel

4. conquer

5. falter

6. fertile

7. foal

8. grumble

9. sturdy

10. vanish

A. a wooden container for liquids

B. to defeat or start controlling a country

C. a baby horse

D. to say that something is true

E. to get, to obtain

F. to disappear

G. strong and solid

H. to moan, to keep complaining

I. likely to produce good crops (about soil)

J. to become weak and ineffective

2.Przekształć wyrażenia według wzoru. Utwórz zdania z trzema z nich.

a sightseeing trip which took a week – a week’s sightseeing trip

a) a holiday which lasted three months – ……………………………………………

b) a rehearsal which will take an hour – ……………………………………………………

c) when a flight is delayed for two hours – ………………………………………………

d) when you slept for fifteen minutes – ………………………………………………………

e) a break which lasted five minutes – …………………………………………………

3. Niektóre zwierzęta wydają mnóstwo różnych niezwykłych dźwięków. Znajdź informacje na ten temat, oglądając np. filmy i programy przyrodnicze. Ułóż listę czasowników opisujących dwięki wydawane przez np. strusia, koalę albo geparda. A jakie dźwięki wydaje czlowiek?

4.Jaka jest historia piosenki „Oh My Darling, Clementine”, którą – obok „La Cucaracha” – wymienia narrator? Opisz historię lub ciekawostki związane z tym utworem (około 250 słów).

Klucz

Rozumienie tekstu

Chapter 1

<<< Powrót

1. Jones

2. Moses

3. Major

4. Boxer

5. Benjamin

6. Mollie

Ćwiczenia

Chapter 1

<<< Powrót

Ćwiczenie 1

1. E

2. D

3. A

4. B

5. J

6. I

7. C

8. H

9. G

10. F

Ćwiczenie 2

a) a three months’ holiday

b) an hour’s rehearsal

c) a two hours’ delay

d) a fifteen minutes’/a quarter’s sleep/nap

e) a five minutes’ break

Ćwiczenie 3

Przykładowa odpowiedź: OSTRICH: chirp, bark, hiss, hum