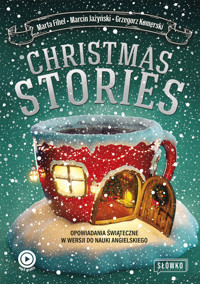

Christmas Stories. Opowiadania świąteczne w wersji do nauki angielskiego ebook

Marta Fihel, Marcin Jażyński, Grzegorz Komerski

Uzyskaj dostęp do tej i ponad 250000 książek od 14,99 zł miesięcznie

- Wydawca: MT Biznes

- Kategoria: Języki obce

- Język: angielski

Język angielski - Poziom B1-B2

Lubisz czytać dobre powieści a jednocześnie chcesz doskonalić swój angielski? Mamy dla Ciebie idealne połączenie! Klasyka literatury światowej w wersji do nauki języka angielskiego.

CZYTAJ – SŁUCHAJ - ĆWICZ

•CZYTAJ– dzięki oryginalnemu angielskiemu tekstowi opowiadań Christmas Stories przyswajasz nowe słówka, uczysz się ich zastosowania w zdaniach i poszerzasz słownictwo. Wciągająca fabuła książki sprawi, że nie będziesz mógł się oderwać od lektury, co zapewni regularność nauki.Czytanie tekstów po angielsku to najlepsza metoda nauki angielskiego.

•SŁUCHAJ– pobierz bezpłatne nagranie oryginalnego tekstu Christmas Stories dostępne na naszej stronie. Czytaj jednocześnie słuchając nagrania i utrwalaj wymowę. W każdej książce znajduje się specjalny kod, który umożliwia pobranie wersji audio (pliki mp3).

•ĆWICZ– do każdego rozdziału powieści przygotowane zostały specjalne dodatki i ćwiczenia:

- na marginesach stron znajdziesz minisłownik i objaśnienia trudniejszych wyrazów;

- w części O słowach poszerzysz słownictwo z danej dziedziny, a w części gramatycznej poznasz struktury i zagadnienia językowe;

- dzięki zamieszczonym na końcu rozdziału testom i różnorodnym ćwiczeniom sprawdzisz rozumienie przeczytanego tekstu;

- odpowiedzi do wszystkich zadań zamkniętych znajdziesz w kluczu na końcu książki.

Boże Narodzenie to magiczny czas, który uwielbiamy spędzać w gronie najbliższych. Specjalnie na tę okazję wybraliśmy związane z tym niezwykłym okresem teksty dziewiętnastowiecznych autorów angielskich i amerykańskich. Nie wszystkie wyszły spod pióra zawodowych literatów – są tu zarówno giganci jak Charles Dickens czy Oscar Wilde, jak i na wpół zapomniani duchowni, dziennikarze, a nawet ornitolodzy. Połączyło ich jedno i to samo pragnienie –podzielić się z innymi historią ciepłą i mądrą. Podobne pragnienie przyświecało nam przy układaniu tego wyboru „opowieści wigilijnych”. Mamy nadzieję, że dzięki tym świątecznym opowieściom uda się ich czytelnikom spędzić kilka przyjemnych chwil i oderwać się od codzienności.

POSZERZAJ SŁOWNICTWO – UTRWALAJ – UCZ SIĘ WYMOWY

Przekonaj się, że nauka języka obcego może być przyjemnością, której nie sposób się oprzeć.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Liczba stron: 394

Rok wydania: 2022

Odsłuch ebooka (TTS) dostepny w abonamencie „ebooki+audiobooki bez limitu” w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Popularność

Podobne

Redakcja: Jadwiga Witecka

Projekt okładki: Amadeusz Targoński | targonski.pl

Zdjęcia na okładce:

© camilkuo | shutterstock.com; © Gilda Tenorio | shutterstock.com;

© Ewais | shutterstock.com; © abramsdesign | shutterstock.com

Skład i łamanie: Protext

Opracowanie e-wydania:

Nagranie, dźwięk i opracowanie muzyczne: Grzegorz Dondziłło, maxx-audio.com

Lektor: Ewa Wodzicka-Dondziłło

Copyright © 2014 by Poltext Sp. z o.o.

Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone. Nieautoryzowane rozpowszechnianie całości lub fragmentów niniejszej publikacji w jakiejkolwiek postaci zabronione. Wykonywanie kopii metodą elektroniczną, fotograficzną, a także kopiowanie książki na nośniku filmowym, magnetycznym, optycznym lub innym powoduje naruszenie praw autorskich niniejszej publikacji. Niniejsza publikacja została elektronicznie zabezpieczona przed nieautoryzowanym kopiowaniem, dystrybucją i użytkowaniem. Usuwanie, omijanie lub zmiana zabezpieczeń stanowi naruszenie prawa.

Dodruk. Warszawa 2022

Poltext Sp. z o.o.

www.wydawnictwoslowko.pl

ISBN 978-83-8175-388-3 (format epub)

ISBN 978-83-8175-389-0 (format mobi)

W wersji do nauki angielskiego dotychczas ukazały się:

A Christmas Carol

Opowieść wigilijna

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Alicja w Krainie Czarów

Animal Farm

Folwark zwierzęcy

Anne of Green Gables

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza

Anne of Avonlea

Ania z Avonlea

Christmas Stories

Opowiadania świąteczne

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen

Baśnie Hansa Christiana Andersena

Fanny Hill. Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

Wspomnienia kurtyzany

Frankenstein

Frankenstein

Heart of Darkness

Jądro ciemności

Little Women

Małe kobietki

Peter and Wendy

Piotruś Pan

Pride and Prejudice

Duma i uprzedzenie

1984

Rok 1984

Sense and Sensibility

Rozważna i romantyczna

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Doktor Jekyll i pan Hyde

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Part 1

Przygody Sherlocka Holmesa

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Part 2

Przygody Sherlocka Holmesa. Ciąg dalszy

The Age of Innocence

Wiek niewinności

The Blue Castle

Błękitny Zamek

The Great Gatsby

Wielki Gatsby

The Hound of the Baskervilles

Pies Baskerville’ów

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Portret Doriana Graya

The Secret Garden

Tajemniczy ogród

The Time Machine

Wehikuł czasu

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Czarnoksiężnik z Krainy Oz

Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog)

Trzech panów w łódce (nie licząc psa)

Wstęp

Długa jesień i jeszcze dłuższa od niej zima, ze swymi długimi i niekiedy dłużącymi się ponad miarę popołudniami i wieczorami stanowią fantastyczny czas na snucie i czytanie opowieści. A jeszcze lepszą okazję na poznanie nowych historii dają nam wypadające na przełomie starego i nowego roku święta Bożego Narodzenia. To właśnie wtedy, po długich rozmowach z bliskimi, zadowoleni z wigilijnych prezentów, z brzuchami pełnymi świątecznych przysmaków, mamy szansę usiąść spokojnie w fotelu, otulić się ulubionym kocem i przeczytać coś nowego. A ponieważ to święta, to powinna być to opowieść ciepła, urocza, napawająca wiarą w świat i ludzi, i – niezależnie od wyznawanej religii czy światopoglądu – w to, że wszystko dobrze się skończy. Bo dlatego właśnie ludzie odkąd tylko nauczyli się mówić, dzielą się opowieściami.

Wybraliśmy dla Was związane (mniej lub bardziej) z Bożym Narodzeniem teksty dziewiętnastowiecznych autorów angielskich i amerykańskich. Nie wszystkie wyszły spod pióra zawodowych literatów – na liście naszych twórców znajdujemy zarówno gigantów takich jak Charles Dickens czy Oscar Wilde, jak i na pół zapomnianych, także w swych ojczyznach, duchownych, dziennikarzy, a nawet ornitologów. Wszystkich tych ludzi połączyło jednak jedno i to samo pragnienie – podzielić się z bliźnimi historią ciepłą i mądrą.

Podobne pragnienie przyświecało nam przy układaniu tekstów do tej książki. Mamy nadzieję, że dzięki tym świątecznym opowieściom uda się państwu spędzić przynajmniej kilka przyjemnych chwil i oderwać się od dręczącej, paskudnej codzienności.

Wesołych Świąt!

Opracowany przez nas podręcznik oparty na oryginalnym tekście baśni i opowiadań został skonstruowany według przejrzystego schematu.

Na marginesach tekstu podano

objaśnienia

trudniejszych wyrazów.

Uwaga! W niektórych utworach pojawiają się niestandardowe formy gramatyczne (np. „There ain’t to be no Christmas for we.”), wyrażenia przestarzałe lub rzadko używane. Ich objaśnienia również znajdują się na marginesach tekstu, ale w ćwiczeniach zwracamy uwagę wyłącznie na słownictwo i struktury, których używa się do dziś w standardowym angielskim.

W objaśnieniach trudniejszych wyrazów użyto następujących skrótów:

l.m. – liczba mnoga

sb – somebody (ktoś)

sth – something (coś)

oneself – się

(franc.) – francuski

(łac.) – łacina

Każde opowiadanie lub baśń zakończono krótkim testem sprawdzającym stopień

rozumienia tekstu

.

Dział

O słowach

, zawarty po każdej części, jest poświęcony poszerzeniu słownictwa, słowotwórstwu, zasadom użycia danego wyrazu, wyrazom kłopotliwym i łatwym do pomylenia, oraz utartym wyrażeniom i zwrotom.

W dziale poświęconym

gramatyce

omówiono wybrane zagadnienia gramatyczne, ilustrowane fragmentami poszczególnych części powieści.

Dla dociekliwych został również opracowany komentarz do wybranych tematów związanych z

kulturą i historią

.

Różnorodne ćwiczenia pozwolą Czytelnikowi powtórzyć i sprawdzić omówione w podręczniku zagadnienia leksykalne i gramatyczne. Alfabetyczny wykaz wyrazów objaśnianych na marginesie tekstu oraz innych trudniejszch słówek znajduje się w słowniczku. Odpowiedzi do wszystkich zadań zamkniętych są podane w kluczu na końcu książki.

PART 1

Słownictwo

How the Pine Tree Did Some Good

Samuel W. Duffield

It was a long narrow valley where the Pine Tree stood, and perhaps if you want to look for it you might find it there today. For pine trees live a long time, and this one was not very old.

The valley was quite barren. Nothing grew there but a few scrubby bushes; and, to tell the truth, it was about as desolate a place as you can well imagine. Far up over it hung the great, snowy caps of the Rocky Mountains, where the clouds played hide and seek all day, and chased each other merrily across the snow. There was a little stream, too, that gathered itself up among the snows and came running down the side of the mountain; but for all that the valley was very dreary.

Once in a while there went a large grey rabbit, hopping among the sagebrushes; but look as far as you could you would find no more inhabitants. Poor, solitary little valley, with not even a cottonwood down by the stream, and hardly enough grass to furnish three oxen with a meal! Poor, barren little valley lying always for half the day in the shadow of those tall cliffs – burning under the summer sun, heaped high with the winter snows--lying there year after year without a friend! Yes, it had two friends, though they could do it but little good, for they were two pine trees. The one nearest the mountain, hanging quite out of reach in a cleft of the rock, was an old, gnarled tree, which had stood there for a hundred years. The other was younger, with bright green foliage, summer and winter. It curled up the ends of its branches, as if it would like to have you understand that it was a very fine, hardyfellow, even if it wasn’t as old as its father up there in the cleft of the rock.

Now the young Pine Tree grew very lonesome at times, and was glad to talk with any persons who came along, and they were few, I can tell you. Occasionally, it would look lovingly up to the father pine, and wonder if it could make him hear what it said. It would rustle its branches and shout by the hour, but the father pine heard him only once, and then the words were so mixed with falling snow that it was really impossible to say what they meant.

So the Pine Tree was very lonesome and no wonder. “I wish I knew of what good I am,” he said to the grey rabbit one day. “I wish I knew, – I wish I knew,” and he rustled his branches until they all seemed to say, “Wish I knew – wish I knew.”

“O pshaw!” said the rabbit, “I wouldn’t concern myself much about that. Some day you’ll find out.”

“But do tell me,” persisted the Pine Tree, “of what good you think I am.”

“Well,” answered the rabbit, sitting up on her hind paws and washing her face with her front ones, in order that company shouldn’t see her unless she looked trim and tidy -”well,” said the rabbit, “I can’t exactly say myself what it is. If you don’t help one, you help another – and that’s right enough, isn’t it? As for me, I take care of my family. I hop around among the sagebrushes and get their breakfast and dinner and supper. I have plenty to do, I assure you, and you must really excuse me now, for I have to be off.”

“I wish I was a hare,” muttered the Pine Tree to himself, “I think I could do some good then, for I should have a family to support, but I know I can’t now.”

Then he called across to the little stream and asked the same question of him. And the stream rippled along, and danced in the sunshine, and answered him. “I go on errands for the big mountain all day. I carried one of your cones not long ago to a point of land twenty miles off, and there now is a pine tree that looks just like you. But I must run along, I am so busy. I can’t tell you of what good you are. You must wait and see.” And the little stream danced on.

“I wish I were a stream,” thought the Pine Tree. “Anything but being tied down to this spot for years. That is unfair. The rabbit can run around, and so can the stream; but I must stand still forever. I wish I were dead.”

By and by the summer passed into autumn, and the autumn into winter, and the snowflakes began to fall.

“Halloo!” said the first one, all in a flutter, as she dropped on the Pine Tree. But he shook her off, and she fell still farther down on the ground. The Pine Tree was getting very churlish and cross lately.

However, the snow didn’t stop for all that and very soon there was a white robe over all the narrow valley. The Pine Tree had no one to talk with now. The stream had covered himself in with ice and snow, and wasn’t to be seen.

The hare had to hop around very industriously to get enough for her children to eat; and the sagebrushes were always low-minded fellows and couldn’t begin to keep up a ten-minutes’ conversation.

At last there came a solitary figure across the valley, making its way straight for the Pine Tree. It was a lamemule, which had been left behind from some wagon-train. He dragged himself slowly on till he reached the tree. Now the Pine, in shaking off the snow, had shaken down some cones as well, and they lay on the snow. These the mule picked up and began to eat.

“Heigh ho!” said the tree, “I never knew those things were fit to eat before.”

“Didn’t you?” replied the mule. “Why, I have lived on these things, as you call them, ever since I left the wagons. I am going back on the Oregon Trail, and I sha’n’t see you again. Accept my thanks for breakfast. Good-bye.”

And he moved off to the other end of the valley and disappeared among the rocks.

“Well!” exclaimed the Pine Tree. “That’s something, at all events.” And he shook down a number of cones on the snow. He was really happier than he had ever been before, – and with good reason, too.

After a while there appeared three people. They were a family of Indians, -a father, a mother, and a little child. They, too, went straight to the tree.

“We’ll stay here,” said the father, looking across at the snow-covered bed of the stream and up at the Pine Tree. He was very poorly clothed, this Indian. He and his wife and the child had on dresses of hare-skins, and they possessed nothing more of any account, except bow and arrows, and a stick with a net on the end. They had no lodge poles, and not even a dog. They were very miserable and hungry. The man threw down his bow and arrows not far from the tree. Then he began to clear away the snow in a circle and to pull up the sagebrushes. These he and the woman built into a round, low hut, and then they lighted a fire within it. While it was beginning to burn the man went to the stream and broke a hole in the ice. Tying a string to his arrow, he shot a fish which came up to breathe, and, after putting it on the coals, they all ate it half-raw. They never noticed the Pine Tree, though he scattered down at least a dozen more cones.

At last night came on, cold and cheerless. The wind blewsavagely through the valleys, and howled at the Pine Tree, for they were old enemies. Oh, it was a bitter night, but finally the morning broke!

More snow had fallen and heaped up against the hut so that you could hardly tell that it was there. The stream had frozentighter than before and the man could not break a hole in the ice again. The sagebrushes were all hid by the drifts, and the Indians could find none to burn.

Then they turned to the Pine Tree. How glad he was to help them! They gathered up the cones and roasted the seeds on the fire. They cut branches from the tree and burned them, and so kept up the warmth in their hut.

The Pine Tree began to find himself useful, and he told the hare so one morning when she came along. But she saw the Indian’s hut, and did not stop to reply. She had put on her winter coat of white, yet the Indian had seen her in spite of all her care. He followed her over the snow with his net, and caught her among the drifts. Poor Pine Tree! She was almost his only friend, and when he saw her eaten and her skin taken for the child’s mantle, he was very sorrowful, you may be sure.

He saw that if the Indians stayed there, he, too, would have to die, for they would in time burn off all his branches, and use all his cones; but he was doing good at last, and he was content.

Day after day passed by, – some bleak, some warm, – and the winter moved slowly along. The Indians only went from their hut to the Pine Tree now. He gave them fire and food, and the snow was their drink. He was smaller than before, for many branches were gone, but he was happier than ever.

One day the sun came out more warmly, and it seemed as if spring was near. The Indian man broke a hole in the ice, and got more fish. The Indian woman caught a rabbit. The Indian child gathered sagebrushes from under the fast-melting snow and made a hotter fire to cook the feast. And they did feast, and then they went away.

The Pine Tree had found out his mission. He had helped to save three lives.

In the summer there came along a band of explorers, and one, the botanist of the party, stopped beside our Pine Tree:

“This,” said he in his big words, “is the Pinus Monophyllus, otherwise known as the Bread Pine.” He looked at the deserted hut and passed his hand over his forehead.

“How strange it is,” said he. “This Pine Tree must have kept a whole family from cold and starvation last winter. There are very few of us who have done as much good as that.” And when he went away, he waved his hand to the tree and thanked God in his heart that it grew there. And the Bread Pine waved his branches in return, and said to himself as he gazed after the departing band: “I will never complain again, for I have found out what a pleasant thing it is to do good, and I know now that every one in his lifetime can do a little of it.”

Rozumienie tekstu

Klucz >>>

Zaznacz poprawne odpowiedzi (A, B lub C).

1. The pine tree

A) had no family.

B) had a friend.

C) made friends with an ox.

2. The rabbit

A) had children.

B) was lonely.

C) couldn’t find anything to eat.

3. The stream

A) didn’t talk to the pine tree.

B) was very busy.

C) felt lonely.

4. The Indian family

A) used what the pine tree gave them.

B) chopped the pine tree down.

C) couldn’t find any food at all.

5. The pine tree

A) felt miserable and lonely all the time.

B) never spoke to his father.

C) was happy to be useful.

SŁOWNICTWO

Charity in a Cottage

Jean Ingelow

The charity of the rich is much to be commended; but how beautiful is the charity of the poor!

Call to mind the coldest day you ever experienced. Think of the bitter wind and driving snow; think how you shook and shivered – how the sharp white particles were driven up against your face – how, within doors, the carpets were lifted like billows along the floors, the wind howled and moaned in the chimneys, windows cracked, doors rattled, and every now and then heavy lumps of snow came thundering down with a dull weight from the roof.

Now hear my story.

In one of the broad, open plains of Lincolnshire, there is a long reedy sheet of water, a favourite resort of wild ducks. At its northern extremity stand two mud cottages, old, and out of repair.

One bitter, bitter night, when the snow lay three feet deep on the ground, and a cutting east wind was driving it about, and whistling in the dry frozen reeds by the water’s edge, and swinging the bare willow trees till their branches swept the ice, an old woman sat spinning in one of these cottages before a moderately cheerful fire. Her kettle was singing on the coals, she had a reed candle, or home-made rushlight, on her table, but the full moon shone in, and was the brighter light of the two. These two cottages were far from any road, or any other habitation; the old woman was, therefore, surprised, in an old northern song, by a sudden knock at the door.

It was loud and impatient, not like the knock of her neighbours in the other cottage; but the door was bolted, and the old woman rose, and shuffling to the window, looked out and saw a shivering figure, apparently that of a youth.

“Trampers!” said the old woman, sententiously, “tramping folks be not wanted here.” So saying she went back to the fire without deigning to answer the door.

The youth upon this tried the door, and called to her to beg admittance. She heard him rap the snow from his shoes against her lintel, and again knock as if he thought she was deaf, and he should surely gain admittance if he could make her hear.

The old woman, surprised at his audacity, went to the casement and with all the pride of possession, opened it and inquired his business.

“Good woman,” the stranger began, “I only want a seat at your fire.”

“Nay,” said the old woman, giving effect to her words by her uncouth dialect, “thou’ll get no shelter here; I’ve nought to give to beggars – a dirty, wet critter,” she continued wrathfully, slamming to the window. “It’s a wonder where he found any water, too, seeing it freeze so hard a body can get none for the kettle, saving what’s broken up with a hatchet.”

The stranger turned very hastily from her door and waded through the deep snow towards the other cottage. The bitter wind helped to drive him towards it. It looked no less poor than the first; and when he had tried the door and found it bolted and fast, his heart sank within him. His hand was so numbed with cold that he had made scarcely any noise; he tried again.

A rush candle was burning within and a matronly looking woman sat before the fire. She held an infant in her arms and had dropped asleep; but his third knock aroused her, and wrapping her apron round the child, she opened the door a very little way, and demanded what he wanted.

“Good woman,” the youth began, “I have had the misfortune to fall in the water this bitter night, and I am so numbed I can scarcely walk.”

The woman gave him a sudden earnest look and then sighed.

“Come in,” she said; “thou art so nigh the size of my Jem, I thought at first it was him come home from sea.”

The youth stepped across the threshold, trembling with cold and wet; and no wonder, for his clothes were completely encased in wet mud, and the water dripped from them with every step he took on the sanded floor.

“Thou art in a sorry plight,” said the woman, “and it be two miles to the nighest house; come and kneel down afore the fire; thy teeth chatter so pitifully I can scarce bear to hear them.”

She looked at him more attentively and saw that he was a mere boy, not more than sixteen years of age. Her motherly heart was touched for him. “Art hungry?” she asked, turning to the table. “Thou art wet to the skin. What hast been doing?”

“Shooting wild ducks,” said the boy.

“Oh,” said the hostess, “thou art one of the keeper’s boys, then, I reckon?”

He followed the direction of her eyes, and saw two portions of bread set upon the table, with a small piece of bacon on each.

“My master be very late,” she observed, for charity did not make her use elegant language, and by her master she meant her husband; “but thou art welcome to my bit and sup, for I was waiting for him. Maybe it will put a little warmth in thee to eat and drink.” So saying, she placed before him her own share of the supper.

“Thank you,” said the boy; “but I am so wet I am making quite a pool before your fire with the drippings from my clothes.”

“Aye, they are wet indeed,” said the woman, and rising again she went to an old box, in which she began to search, and presently came to the fire with a perfectly clean check shirt in her hand and a tolerably good suit of clothes.

“There,” said she, showing them with no small pride, “these be my master’s Sunday clothes, and if thou wilt be very careful of them I’ll let thee wear them till thine be dry.” She then explained that she was going to put her “bairn” to bed, and proceeded up a ladder into the room above, leaving the boy to array himself in these respectablegarments.

When she had come down her guest had dressed himself in the labourer’s clothes; he had had time to warm himself, and he was eating and drinking with hungry relish. He had thrown his muddy clothes in a heap upon the floor. As she looked at him she said:

“Ah, lad, lad, I doubt that head been under water: thy poor mother would have been sorely frightened if she could have seen thee a while ago.”

“Yes,” said the boy; and in imagination the cottage dame saw this same mother, a careworn, hard-working creature like herself; while the youthful guest saw in imagination a beautiful and courtly lady; and both saw the same love, the same anxiety, the same terror, at sight of a lonely boy struggling in the moonlight through breaking ice, with no one to help him, catching at the frozen reeds, and then creeping up, shivering and benumbed, to a cottage door.

But, even as she stooped, the woman forgot her imagination, for she had taken a waistcoat into her hands, such as had never passed between them before; a gold pencil-case dropped from the pocket; and on the floor amidst a heap of mud that covered the outer garments, lay a white shirt sleeve, so white, indeed, and so fine, that she thought it could hardly be worn by a squire!

She glanced from the clothes to the owner. He had thrown down his cap, and his fair curly hair and broad forehead convinced her that he was of gentle birth; but while she hesitated to sit down, he placed a chair for her, and said with boyish frankness:

“I say, what a lonely place this is! If you had not let me in, the water would have frozen me before I reached home. Catch me duck-shooting again by myself!”

“It’s very cold sport that, sir,” said the woman.

The young gentleman assented most readily, and asked if he might stir the fire.

“And welcome, sir,” said the woman.

She felt a curiosity to know who he was, and he partly satisfied her by remarking that he was staying at Deen Hall, a house about five miles off, adding that in the morning he had broken a hole in the ice very near the decoy, but it iced over so fast, that in the dusk he had missed it, and fallen in, for it would not bear him. He had made some landmarks, and taken every properprecaution, but he supposed the sport had excited him so much that in the moonlight he had passed them by.

He then told her of his attempt to get shelter in the other cottage.

“Sir,” said the woman, “if you had said you were a gentleman -”

The boy laughed. “I don’t think I knew it, my good woman,” he replied, “my senses were so benumbed; for I was some time struggling at the water’s edge among the broken ice, and then I believe I was nearly an hour creeping up to your cottage door. I remember it all rather indistinctly, but as soon as I had felt the fire and eaten something I was a different creature.”

As they still talked, the husband came in; and while he was eating his supper it was agreed that he should walk to Deen Hall, and let its inmates know of the gentleman’s safety. When he was gone the woman made up the fire with all the coal that remained to the poor household, and crept up to bed, leaving her guest to lie down and rest before it.

In the grey dawn the labourer returned, with a ser-vant leading a horse, and bringing a fresh suit of clothes.

The young man took his leave with many thanks, slipping three half-crowns into the woman’s hand, probably all the money he had about him. And I must not forget to mention that he kissed the baby; for when she tells the story, the mother always adverts to that circumstance with great pride, adding that her child, being as “clean as wax, was quite fit to be kissed by anybody.”

“Misses,” said her husband, as they stood in the doorway looking after their guest, “who dost think that be?”

“I don’t know,” answered the misses.

“Then I’ll just tell thee; that be young Lord W----; so thou mayest be a proud woman; thou sits and talks with lords, and then asks them to supper – ha, ha!”

So saying, her master shouldered his spade and went his way, leaving her clinking the three half-crowns in her hand, and considering what she should do with them.

Her neighbour from the other cottage presently stepped in, and when she heard the tale and saw the money her heart was ready to break with envy and jealousy.

“Oh, to think that good luck should have come to her door, and she should have been so foolish as to turn it away! Seven shillings and sixpence for a morsel of food and a night’s shelter--why it was nearly a week’s wages!”

So there, as they both supposed, the matter ended, and the next week the frost was sharper than ever. Sheep were frozen in the fenny field and poultry on their perches, but the good woman had walked to the nearest town and bought a blanket. It was a welcomeaddition to their bed covering, and it was many a long year since they had been so comfortable.

But it chanced one day at noon that, looking out at her casement she spied three young gentlemen skating along the ice towards her cottage. They sprang on to the bank, took off their skates, and made for her door. The young nobleman, for he was one of the three, informed her that he had had such a severe cold he could not come to see her before. “He spoke as free and pleasantly,” she said, in telling the story, “as if I had been a lady, and no less, and then he brought a parcel out of his pocket, saying, ‘I have been over to B---- and brought you a book for a keepsake, and I hope you will accept it;’ and then they all talked as pretty as could be for a matter of ten minutes, and went away. So I waited till my master came home, and we opened the parcel, and there was a fine Bible inside, all over gold and red morocco, and my name and his name written inside; and, bless him, a ten-pound note doubled down over the names. I’m sure, when I thought he was a poor forlorn creature, he was kindly welcome. So my master laid out part of the money in tools, and we rented a garden; and he goes over on market days to sell what we grow, so now, thank God, we want for nothing.”

This is how she generally concludes the little history, never failing to add that the young lord kissed her baby.

But I have not yet told you what I thought the best part of the story. When this poor Christian woman was asked what had induced her to take in a perfect stranger and trust him with the best clothing her home afforded, she answered simply, “Well, I saw him shivering and shaking, so I thought, thou shalt come in here, for the sake of Him that had not where to lay His head.”

The old woman in the other cottage may open her door every night of her future life to some forlorn beggar, but it is all but certain that she will never open it to a nobleman in disguise!

Let us do good, not to receive more good in return, but as evidence of gratitude for what has been already bestowed. In a few words, let it be “all for love and nothing for reward.”

“The most excellent gift is charity.”

Lista Autorów

Samuel Willoughby Duffield (24 września 1843–12 maja 1887) – Amerykański duchowny i pisarz.

Jean Ingelow (17 marca 1820–20 lipca 1897) – Dziewiętnastowieczna brytyjska poetka, powieściopisarka, autorka literatury dziecięcej.

Charles Lamb (10 lutego 1775–27 grudnia 1834) – Angielski eseista, poeta i antykwariusz. Znany ze zbioru „Essays of Elia” i napisanej wspólnie z siostrą Mary książki dla dzieci „Tales from Shakespeare”. Przyjaźnił się z tak znanymi literatami, jak Samuel Taylor Coleridge czy William Wordsworth.

Dallas Lore Sharp (13 grudnia 1870–1929) – Amerykański duchowny, pisarz, profesor uniwersytecki i ornitolog. Szczególnie znany z cyklu ilustrowanych artykułów prasowych opisujących zamieszkujące USA gatunki ptaków.

Oscar Wilde (16 października 1854–30 listopada 1900) – Angielski poeta, dramaturg, filolog i prozaik. Jeden z najbardziej znanych i cenionych autorów swojej epoki. Pamiętany szczególnie za powieść „Portret Doriana Graya”.

John Mason Neale (24 stycznia 1818–6 sierpnia 1866) – Anglikański pastor, uczony, tłumacz i autor hymnów religijnych.

Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman (31 października 1852–13 marca 1930) – Popularna i wpływowa amerykańska autorka literatury dziecięcej. W jej utworach świat rzeczywisty nierzadko spotykał się z nadnaturalnym. Nieobce były jej problemy społeczne. Jedna z pierwszych przedstawicielek ruchu feministycznego.

Harriet Mann Miller (tworząca pod pseudonimami Olive Thorne i Olive Thorne Miller) (25 czerwca 1831–25 grudnia 1918) – Amerykańska pisarka, przyrodniczka i ornitolożka.

Katharine Pyle (23 listopada 1863–19 lutego 1938) – Amerykańska malarka, ilustratorka prasowa, poetka i autorka książek dla dzieci.

Juliana Horatia Ewing (3 sierpnia 1841–13 maja 1885) – Angielska autorka opowiadań dla dzieci. Jej twórczość charakteryzowało głębokie zrozumienie dziecięcej duszy, podziw dla wojska i silna wiara religijna.

Elia Wilkinson Peattie (15 stycznia 1862–12 lipca 1935) – Amerykańska pisarka, dziennikarka i krytyczka.

Anne Hollingsworth Wharton (15 grudnia 1845–29 lipca 1928) – Amerykańska pisarka i historyk.

Oliver Bell Bunce (8 lutego 1828–15 maja 1890) – Amerykański pisarz, wydawca i dramaturg.

Henrietta Eliza Vaughan Stannard (1856–1911) pisząca pod pseudonimem John Strange Winter – brytyjska powieściopisarka.

Sarah Chauncey Woolsey (29 stycznia 1835–9 kwietnia 1905) – Amerykańska autorka literaturydziecięcej, tworząca pod pseudonimem Susan Coolidge. Znana m.in. z książek „Po prostu Katy” (What Katy did, 1872) i „Co Kasia robiła w szkole” (What Katy Did at School, 1873).

Charles Dickens – patrz notka do części 6.